The Church of Mar-Méma in Ehden traces its origins, according to Patriarch Estephanos Douaihy, to the year 749. This architecture, a genuine open book, preserves a Greek inscription from the year 272 and a Syriac epigraph dated 790. It thus bears witness to the transition, around the sixth century, from Greek to Syriac in the field of stone inscriptions.

Mar Méma, or Saint Mammes, was a young Cappadocian who suffered martyrdom at 16 years old in the city of Caesarea in 274. Several churches and monasteries in Lebanon have been dedicated to him, and some villages still bear his name, including Mar Méma in the Batroun mountains and Deir Mimas in the district of Marjayoun.

Among the churches, Mar-Méma in Ehden is arguably the most significant, both for its age – dating back to 749 in its Christian form – and for the traces it preserves of the pagan sanctuary that formerly stood on the site. These remnants are still visible in the current facades, particularly in the door jambs. The masonry also bears several bicorned and tricorned crosses, characteristic of Maronite antiquity from the fifth and sixth centuries. The apse’s floor pavement still retains fragments of the original white mosaic.

Greek Inscription

Like many churches in the Byblos and Batroun mountains, Mar-Méma preserves a Greek inscription characteristic of the period before Syriac came into use. Epigraphy in Mount Lebanon shows that, in the realm of stone inscriptions, Greek was replaced by Syriac only from the sixth century onward. The Greek inscription from Mar-Méma in Ehden was removed by Ernest Renan in 1861 and is now housed in the Louvre Museum under inventory number 4524. It is clearly dated to year 584 of the Seleucid era, or 272 AD. A second Greek inscription is engraved on a tomb opposite the church.

Once again, Maronite Patriarch Estephanos Douaihy provides the date of this church’s construction in his Candelabrum of the Holy Mysteries. He wrote that the “Holy Fathers divided major places of worship into three parts—the Holy of Holies, the Sanctuary, and the nave—reflecting the Persons of the Trinity. This layout can be seen in many of our ancient churches, including Mar-Méma in Ehden, built in 749; Mar-Séba in Bcharré, from 1112; Mar-Doumit in Toula, in the Batroun region; Mar-Charbel in the village of Maad, in the Jbeil region; and others.”

As with Mar-Charbel in Maad, Mar-Nohra in Smar-Jbeil and Mar-Séba in Eddé, the church of Ehden was also built with three naves. Unfortunately, one of them was lost when the road was widened carelessly along its side.

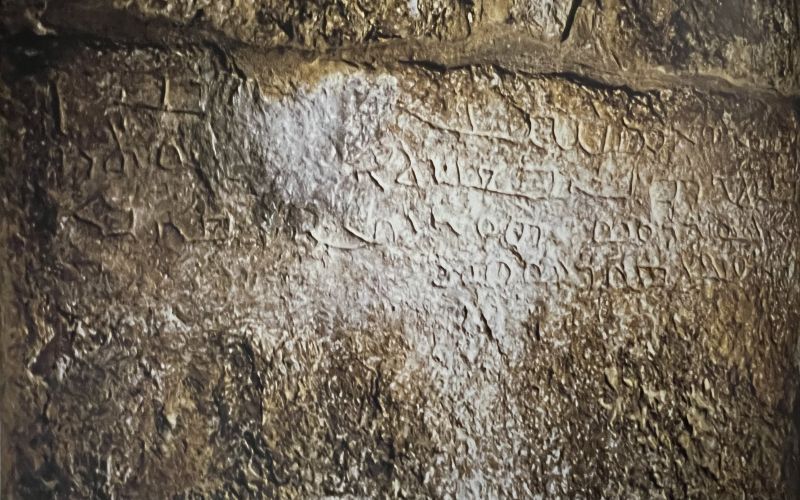

Syriac Inscription

The building has undoubtedly undergone several alterations over the course of its history, after it was first built in 749. This is evidenced by reused stones embedded here and there in the masonry, and above all by its Syriac inscription, also dated to the eighth century. Strikingly, this epigraph is set upside down in the base of the pier to the right of the altar. Dated to the year 790, it shows that, 40 years after it was first built, the church was restructured down to its very foundations.

This Syriac epigraph, copied and translated by Ernest Renan, was later cited by Father Henri Lammens, Viscount Philippe de Tarazi and Henri Leclercq. Renan’s translation, reproduced by Leclercq, translates it as an epitaph: “In the name of God who raises the dead… in the year 1… of Alexander… Morcos fell asleep and died…”

The Syriac Inscription of the Year 790 (Syriaque Epigraphy in Lebanon, by Amine Jules Iskandar, Louaizé, Lebanon, NDU Press, 2008.)

However, this interpretation contains several inaccuracies, particularly in the name of Mark, which was read as Morkos, whereas Syriac requires the form Morqos. A closer reading by Father Gaby Abousamra makes it possible to identify the date. We therefore translate it as: “In the name of God who raises the dead and who is alive; this house was built in the year one thousand one hundred and two of Alexander… It was… who oversaw the work and struck his hammer.”

The Antiochene Era

As with many Greek and Syriac inscriptions, a cross marks the start of the text. The script uses the monumental square Estrangelo style, typical of the Maronites, especially during the Middle Ages. The date 1102 is given according to Alexander – that is, the Seleucid or Antiochene era – and corresponds to the Christian year 790–791. The Syriac Maronite Antiochian Church continued to use the Antiochene era until the founding of the Maronite College in Rome in 1584.

This second reading no longer alludes to an epitaph but to the commemoration of the founding of the church. The phrase “to drop one’s hammer” in the text marks the inauguration of construction. The building is called Bayto, which is unusual for a church, normally designated as Idto or Hayklo, or as Oumro or Dayro in the case of a monastery. The date is also quite faint and seems to combine Syriac numerals with numbers written out in words. Therefore, our interpretation remains somewhat uncertain.

Mar-Méma of Ehden is both a treasure of heritage and an open book on our history. As always, the architectural legacy and the writings of Patriarch Estephanos Douaihy come together to illuminate and preserve our past. Within a single monument, we witness the transition from Greek to Syriac in our stone inscriptions, all of which remained faithful to the Antiochene era. This era and its heritage are characteristic of the Maronite tradition, enduring even through its later Latinization.

Comments