A Syrian delegation is expected in Beirut later this month to address outstanding issues between the two countries.

Since the fall of Bashar al-Assad in December 2024 and the election of Ahmad al-Sharaa as Syria’s president, a new dynamic has emerged. For Lebanon, this represents both an opportunity to build a more balanced relationship with Damascus and a potential risk, given the unresolved disputes that remain.

Prudent Diplomacy

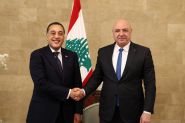

Lebanon has taken a series of measured diplomatic steps since January. Former Prime Minister Najib Mikati visited Damascus to break the ice, followed in April by current Prime Minister Nawaf Salam, who announced the formation of joint committees on security and border issues.

Lebanon’s mufti, Sheikh Abdellatif Derian, also traveled to Damascus in July, giving the rapprochement a national and religious dimension. Yet, Damascus has not sent an official representative to Beirut.

Speaking on Sunday in Damascus to an Arab delegation, Sharaa expressed his intent to establish “a state-to-state relationship with Lebanon, based on economic solutions, stability and shared interests, free from interference.” He acknowledged that “Lebanon has suffered from Assad-era policies” and called for “writing a new history” and moving beyond the legacy of the past. He added that “Syria’s investment in Lebanon’s sectarian polarization was a grave mistake and must not be repeated.”

Syrian Prisoners: Damascus’ Key Leverage

The most sensitive issue remains the Syrian prisoners held in Lebanon, estimated at over 2,000. This includes former Free Syrian Army (FSA) members arrested after the 2014 Ersal clashes, alongside common-law detainees and political opponents.

Roumieh Prison’s infamous “Block B” houses around 500 Islamist detainees, including 150 Syrians held without trial for 5 to 12 years. The facility is overcrowded at 250% of capacity and has witnessed multiple incidents this year, including hunger strikes, riots and sit-ins by relatives at the Jousieh border post.

Damascus is now demanding their full repatriation. A Syrian delegation, including representatives from the judiciary, military and intelligence services, is expected in Beirut to negotiate an agreement.

Refugees: An Unsustainable Burden

Lebanon hosts nearly 2 million Syrians, including economic migrants, displaced persons and refugees, of whom 750,000 are officially registered, giving the country the world’s highest per-capita refugee burden.

For Beirut, the situation is both a political and social emergency, compounded by the ongoing economic crisis. Sharaa has called for “gradual returns with guarantees,” rejecting mass reintegration that could destabilize his still-new authority.

The flow of Syrians has not abated. Following recent violence on the Syrian coast and in Sweida, arrivals have increased: in March alone, 21,000 Alawite Syrians sought refuge in northern Lebanon, raising the risk of sectarian tensions in Sunni-majority areas such as Tripoli and Akkar.

Bank Deposits: Between Recovery and Ruin

Another area of tension is financial. Syrian deposits frozen in Lebanese banks are claimed by Damascus to total tens of billions of dollars, while Lebanese estimates place the figure between 3 and 10 billion.

For Syria, these funds are crucial funding for reconstruction. For Lebanon, their release is constrained by the broader banking crisis that has gripped the country since 2019. The stalemate endures, a stark reflection of the deep mutual distrust between Beirut and Damascus.

Borders: Smuggling and Clashes

The 330-kilometer border remains porous. The Washington Institute has identified 130 illegal crossings, including 53 in the Beqaa, used for arms flows and, in particular, the Captagon trade.

In February and March, armed skirmishes erupted between the Lebanese Army, Syrian forces and local tribes in northern Beqaa. On March 28, the defense ministers of both countries signed a preliminary border demarcation agreement in Saudi Arabia under Riyadh’s sponsorship. However, implementation has yet to begin. The case of the Shebaa Farms, still occupied by Israel and never officially demarcated, remains a central obstacle. As long as the ambiguity persists, Hezbollah retains its justification for keeping its arsenal.

Hezbollah: From Ally to Burden

Perhaps the clearest sign of change in the post Assad era is Hezbollah’s altered status. Once considered Damascus’ indispensable ally, the Shia movement is now seen by Sharaa as a heavy legacy of the Assad years.

“We have moved beyond the wounds Hezbollah inflicted on Syria,” Sharaa acknowledged, while stressing that his country will not be used by those seeking to confront the party. “We are neither an existential threat nor a bargaining chip against Hezbollah,” he insisted.

In both Beirut and Damascus, reconciliation rhetoric now dominates. The real test is whether actions will follow words this time.

Comments