The Château of Saint-Gilles, built between 1103 and 1109 on Mont-Pèlerin, was later remodeled by the Ottoman governor appointed to Tripoli in 1798. During restoration, he repurposed limestone tombstones taken from a nearby Maronite cemetery. Carved with Syriac epitaphs and dating from 1719 to 1788, these stones remain embedded throughout the castle’s masonry.

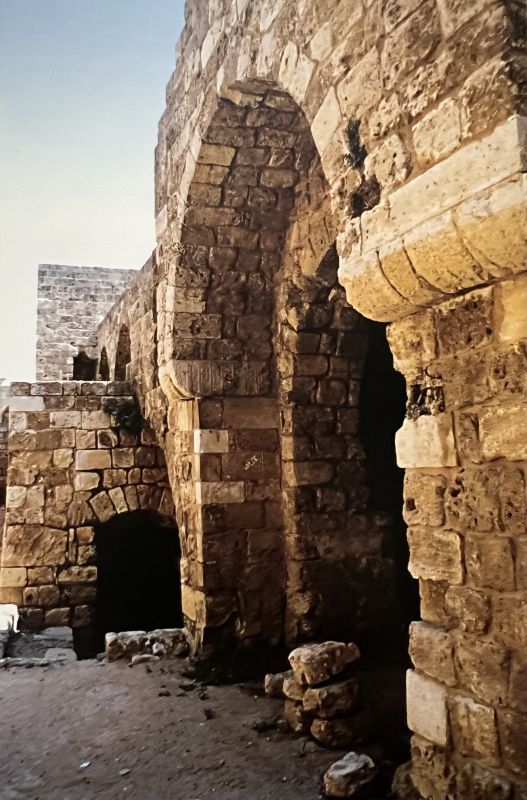

Christian rule over Tripoli came to an end with the death of Byzantine emperor Nicephorus II Phocas in 969. Some 130 years later, the Crusaders reached the city gates and found a fortified settlement where the Arabs had firmly consolidated their presence. Despite reinforcements from the Christian mountain regions, it took them a full decade to gain entry into Tripoli. During that long siege, a citadel was constructed on Mont-Pèlerin, overlooking the city.

The Castle

Three years after the fall of Jerusalem in 1099, Raymond of Saint-Gilles, the Count of Toulouse, began building the fortress overlooking the ancient city. Over several years, Crusader forces launched repeated attacks from the stronghold, steadily expanding their control throughout the conflict until the Christians finally entered the city in 1109. Raymond, who fell in battle in 1105, never witnessed this victory. His son Bertrand succeeded him, taking on the titles of Count of Toulouse and Tripoli. Mont-Pèlerin became the seat of power for the newly formed county of Tripoli.

In the second half of the 13th century, as the Latin states began to collapse under pressure from the Mamluk armies, Tripoli held a strategic advantage due to its position along the edge of the Christian mountain regions. It drew strength from a network of fiefdoms, among which the lordship of Buissera (modern-day Bcharreh) stood out for its size, geography and demography.

But in 1271, the Mamluk sultan Baybars, after capturing the Krak des Chevaliers, dealt a major blow to the county. In 1283, his successor, Qalawun, devastated the lordship of Buissera, carrying out a massacre that reached into the Qadisha caves, where the population had taken refuge. Tripoli eventually fell in 1289, and the Mamluks seized the Château of Saint-Gilles, holding it until the arrival of the Ottomans in 1516.

The Ottomans

In 1798, Mustapha Barbar Agha was appointed governor of Tripoli by the Ottomans. He immediately initiated the most extensive restorations and architectural modifications of the Crusader castle. His builders employed the typical sandstone masonry found along the Levantine coast. Yet, within the confined space of a citadel, upper floors often extended beyond the ground level. Corbelled structures were commonly used to support these overhangs, requiring harder materials to redirect the load.

The durable material was sourced from Christian territories, particularly their cemeteries. Although the Maronite villages were also built with sandstone, their tombstones were crafted from hard limestone, better suited for inscriptions. As a result, an entire Maronite cemetery was incorporated into the new masonry of the Château of Saint-Gilles.

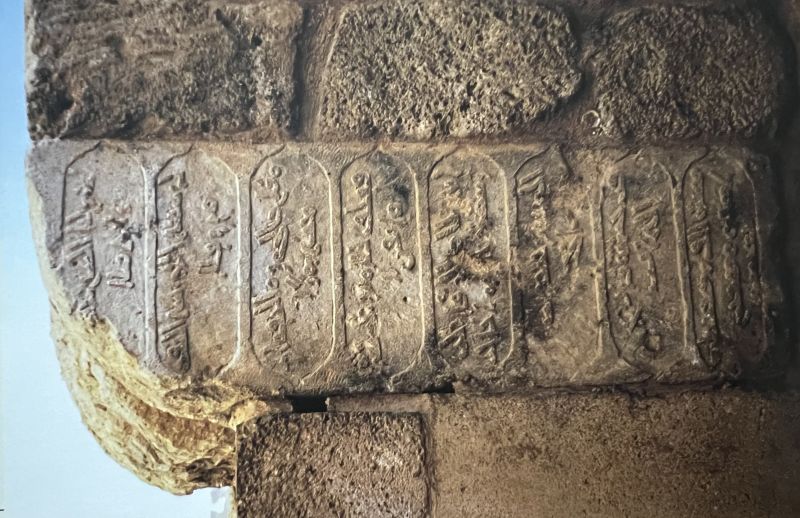

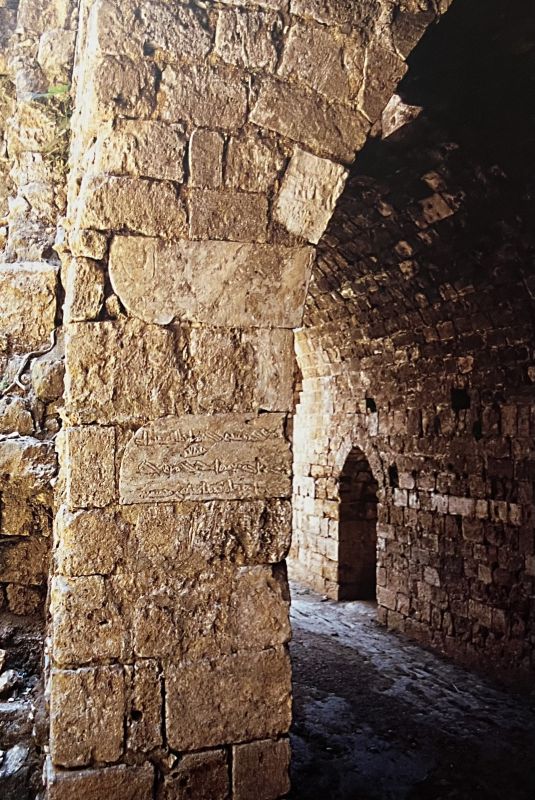

A careful observer cannot fail to notice that the corbel stones are in fact funerary epitaphs. Syriac inscriptions appear on the brackets supporting the bases of vaults and arches. Some are oriented correctly, others upside down, while a few are nearly concealed within the thickness of the masonry.

White tombstones repurposed as corbel supports.

The Tombstones

As these are funerary slabs, all the inscriptions bear dates. They date back to the eighteenth century and are written in Garshuni, a form of Arabic rendered in Syriac script. The inscriptions identified range from 1719, 1737, 1754, 1777, 1779, 1780 to 1788. This indicates that the cemetery repurposed by Mustapha Barbar Agha, appointed governor in 1798, was relatively recent and far from abandoned.

While the dates remain clearly visible, the names of the deceased were deliberately erased to accommodate the builders’ needs. These tombstones were trimmed and shaped to form brackets and corbels with curved edges. Other inscriptions were partially embedded within walls, obscuring parts of the text.

One of the slabs, dated 1719, was removed from its original location and is now displayed in the castle’s small museum. It is the only one of smaller dimensions, measuring about thirty centimeters, while the others range between 60 and 100 centimeters. It commemorates a man named Elias, who died on April 13.

The Epitaphs

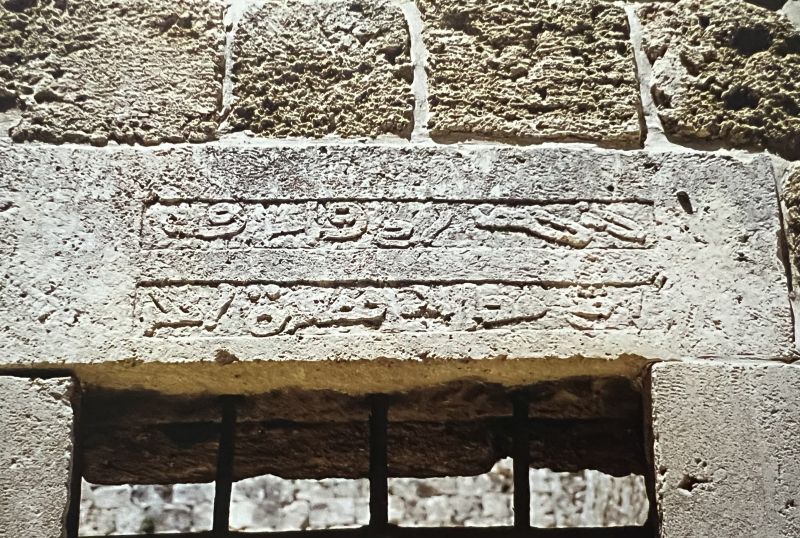

The epitaph from 1737 stands out for its unusual placement as a window lintel. It is also notably brief, mentioning only the name Gerges, son of Fayez, along with the date of February 8 and the year.

The 1737 epitaph was used as a window lintel.

As with the other examples, the epitaph from 1754 is composed of recessed bands with pointed or arched ends. Each band contains, in accordance with Syriac tradition, one or two lines of text. The absence of the ends on one side indicates that half of the stone, and therefore half of the inscription, is missing. From what remains, the names Khoury, Moussa and Hanna can be identified. The date is written using the Syriac letters “olaph,” “ain,” “noun” and “dolat,” corresponding to 1754.

The stone from 1777 is unique in that it bears inscriptions on two sides. Set into a vault and carved into the shape of a bracket, only the year and the beginning of a prayer invoking God’s fullness remain visible.

Measuring 95 centimeters in length, the epitaph from 1779 contains seventeen lines of text, arranged in pairs within bands ending in broken arches. Following the customary phrase, “He passed to the mercy of God, to forgiveness, generosity and blessings,” it names the priest Issa, who died in the month of January.

The 1779 epitaph.

Although carved in the shape of a bracket, the epitaph from 1780 ended up embedded as ordinary masonry within a wall. Nevertheless, it has preserved all six of its inscribed bands. Each band contains two clearly legible lines, arranged around a central cross. As with most of the epitaphs, it opens with the phrase, “Glory be to God forever; has passed to the mercy of the Lord...”

The inscription from 1788 is remarkably simple, with no banded layout. Like others, it was carved to serve as a bracket, but ultimately ended up embedded as plain masonry in the wall. Dated September 15, 1788, it sits adjacent to a second, identical stone that appears to bear an epitaph on its hidden side. This is likely true of many other examples that remain to be uncovered.

The 1788 epitaph, carved as a bracket and embedded in the masonry.

Photos from Épigraphie Syriaque au Liban vol.1, by Amine Jules Iskandar, Louaizé, Lebanon, NDU Press, 2008.

Comments