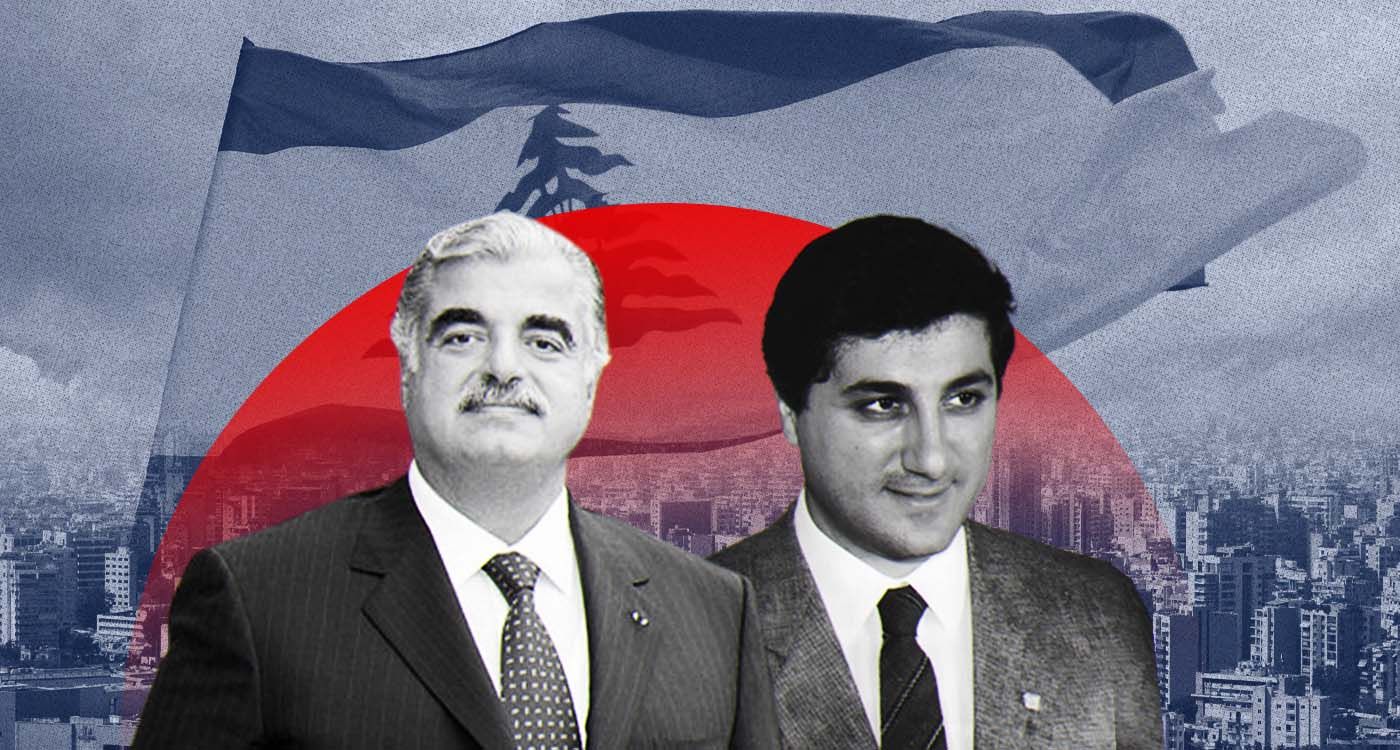

In Lebanon’s fractured modern history, two names stand out not just as political leaders, but as symbols of diverging strategies for saving a nation: Bachir Gemayel, the Christian militia leader turned president-elect, and Rafic Hariri, the Sunni businessman who became Lebanon’s post-war prime minister. Their stories are not simply about personal ambition, they represent two contrasting yet interconnected visions for Lebanon’s survival.

Bachir Gemayel rose from the chaos of civil war as the embodiment of Maronite determination to preserve Lebanon’s “Christian essence.” For Gemayel, Lebanon’s survival hinged on defending its identity as a Western-oriented, pluralistic, yet distinct entity amidst Arab nationalism, Palestinian militarization and Syrian intervention. His leadership of the Lebanese Forces was as much ideological as it was military.

Bachir Gemayel believed that if Lebanon lost its unique identity, politically, culturally and demographically, it would cease to exist. His short-lived presidency was set to implement this vision through a strong centralized state, stripping militias (including his own) of weapons, and pushing for full sovereignty free from Syrian and Palestinian control. His assassination in 1982 not only ended his personal project but also derailed any serious attempt at unifying Lebanon under a Maronite-led national state.

By the time Hariri entered the scene, Lebanon had been gutted by war. For Hariri, identity politics was a dead-end. His vision was economic, rebuilding Beirut as the Middle East’s Paris, attracting Gulf money and positioning Lebanon as a regional financial hub. His project was pragmatic: stabilize, rebuild and integrate Lebanon economically into the Arab world, especially aligning with Saudi Arabia and the West.

Hariri believed that if Lebanon’s roads, banks and real estate thrived, sectarian divisions might heal or at least become manageable. His assassination in 2005, ironically blamed on the Syrian regime that Bachir Gemayel opposed, revealed that infrastructure without sovereignty was unsustainable.

Gemayel tried to protect Lebanon’s identity. Hariri tried to rebuild its body. Both failed, arguably, because Lebanon’s “soul” was already compromised.

Gemayel underestimated the resilience of Arab nationalism, Palestinian militarization and Syria’s imperial ambitions, as well as the divisions within Lebanon’s own Christian factions. Hariri underestimated Hezbollah’s rise, Syria’s entrenchment and the extent to which sectarianism could resist economic pragmatism.

Their visions were not mutually exclusive, perhaps one needed the other. Identity without prosperity is sterile, prosperity without sovereignty is vulnerable.

Here lies the most controversial question. Were Lebanese Christians, particularly the Maronites, right in their political instincts?

From a geopolitical lens, yes, but too early and too alone. Their warnings about Syrian occupation, Palestinian militarization and Iran’s expansion through Hezbollah have all materialized as existential threats. However, their strategies were often isolationist, rigid and unwilling to compromise until too late. Their early alliances with Israel alienated many Lebanese, and their over-reliance on military solutions ignored Lebanon’s pluralistic reality.

Christians were right in diagnosing the threats, but often wrong in treating them.

Bachir Gemayel and Rafic Hariri personify Lebanon’s divided rescue attempts: one prioritizing identity, the other rebuilding. Both were assassinated before their visions could mature. Today, Lebanon drifts without a compass, still torn between sovereignty and survival, identity and economy, East and West.

Perhaps Lebanon’s tragedy is that it never found a leader who could merge Bachir Gemayel’s sovereignty-first mindset with Rafic Hariri’s rebuilding pragmatism.

In the end, both men tried to save Lebanon, each in his way. Both were right. And both were defeated.

Comments