- Home

- Middle East

- Immigration Dominates London–Paris Talks

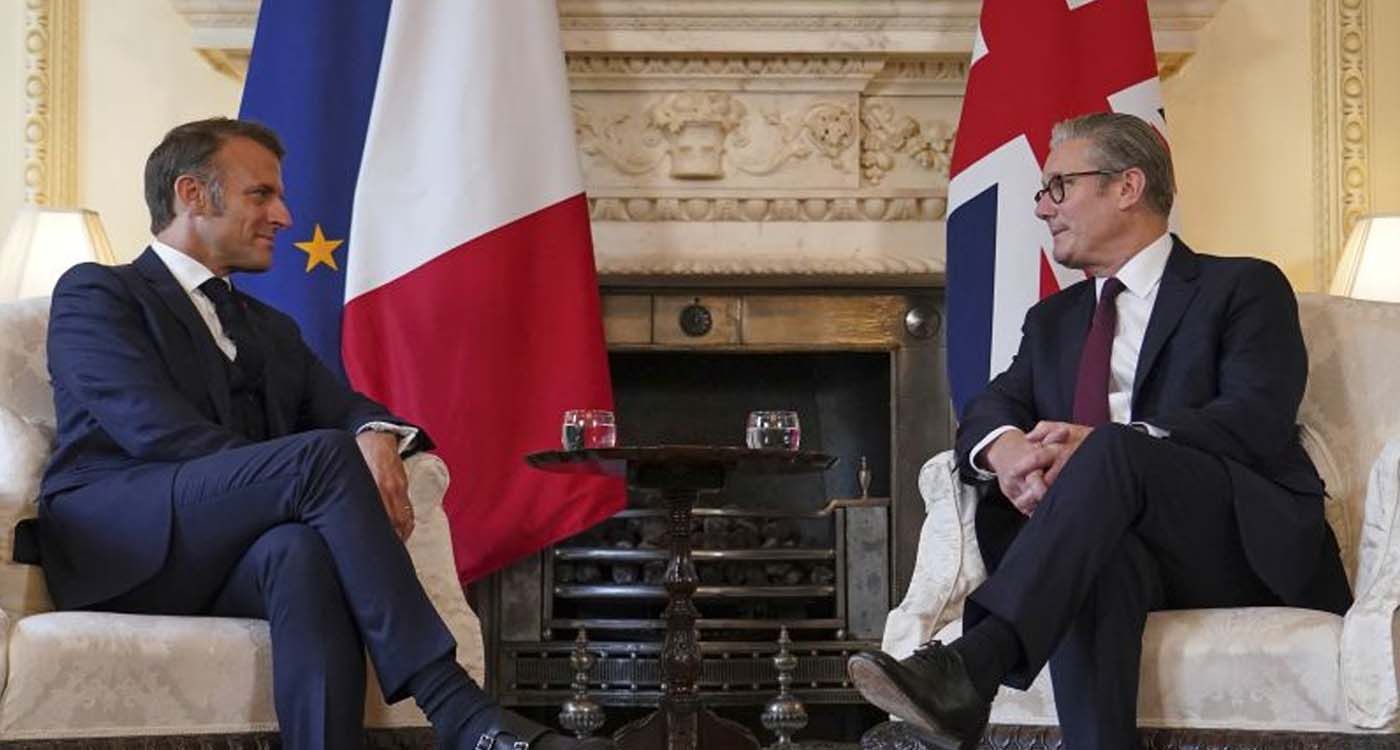

©Alberto Pezzali/AFP

It was the issue that hovered over the visit, that was present in every conversation, though absent from the red carpet. On Wednesday, July 9, illegal immigration across the English Channel took center stage as French President Emmanuel Macron met with the United Kingdom’s new Prime Minister, Keir Starmer.

So far this year, more than 20,000 immigrants have attempted the dangerous crossing in small boats, a record figure that has intensified political pressure on both sides of the Channel and underscored the urgency of a coordinated response.

The UK is pushing for a new approach. Beyond the 2018 Sandhurst Treaty, which provided British funding to help France secure its northern coastline, London is now proposing a bold mechanism: return immigrants who illegally reach British shores in exchange for accepting an equal number of registered refugees. A “one-for-one” scheme, as it’s been described – one the French government is approaching with caution.

Paris is reluctant to become a sorting ground for the UK’s asylum system. Still, the Élysée has expressed willingness to strengthen efforts to stop departures. Macron has approved an expansion of France’s maritime enforcement doctrine, allowing French forces to intervene just meters from shore before boats leave national waters. It is a technical adjustment, but one with heavy symbolic and political implications.

“We want tangible results,” said Macron. But on the ground, the challenge is immense. Smugglers continue to adapt, crossings persist and new strategies often leave the underlying dynamics untouched.

NGOs have denounced what they call a security-first approach, while immigration experts warn of a dangerous cycle: the more repatriation, the more people are likely to try again.

No new agreement has been signed, but the political will to reset the conversation is clear – precisely what Macron was seeking in his first meeting with Starmer: a pragmatic, post-Brexit partner ready to rethink cooperation.

What’s at stake may extend beyond the English Channel. It could mark the beginning, so far incomplete, of a new way to approach immigration, at a time when borders around the world are closing faster than they are being negotiated.

Read more

Comments