- Home

- Highlights

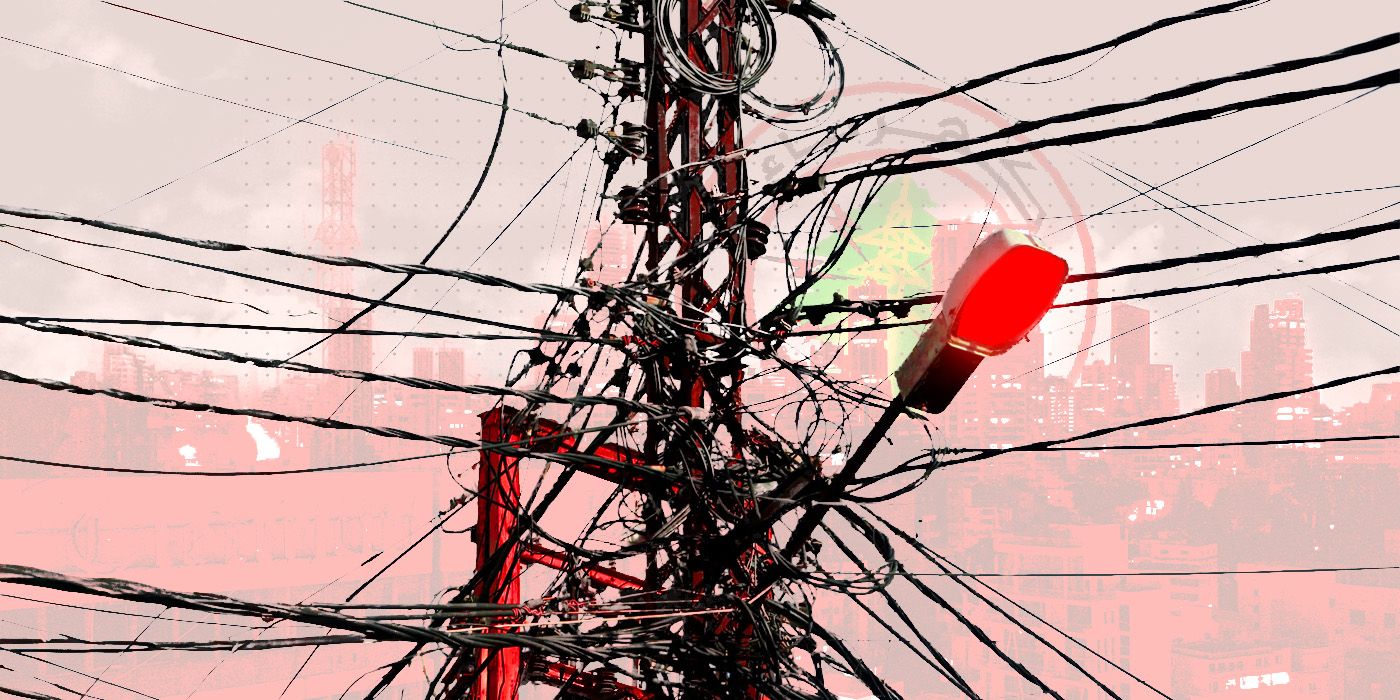

- EDL: At the Heart of Lebanon’s Energy Crisis

©This is Beirut

Electricity rationing is the rule, contrary to all logic in a nation-state framework. A quarter of a century after the end of the Civil War, the Lebanese remain dependent on alternative means of energy supply – mostly at the mercy of the neighborhood private generator supplier. Électricité du Liban (EDL) will long remain in Lebanon’s history books as a symbolic example of the structural failures of the public sector.

However, after hitting rock bottom with the nationwide blackout on August 17, 2024, the Lebanese can now glimpse the early signs of an energy recovery – still fragile, but full of hope – supported by serious reform initiatives. Yet, these are constantly hampered by heavy-handed administrative routines, often exploited by behind-the-scenes political squabbles, and by international initiatives tied to numerous conditions.

A Recurring Blackout

The total blackout on August 17, 2024, remains etched in the collective memory of the Lebanese, just as brutal as the one on October 9, 2021. Both times, the state failed in its most basic mission: to provide electricity. Unable to unlock the necessary funds to import fuel for EDL, the government let the turbines of power plants fall silent – a stark symbol of a system on the brink of collapse. The disruption of electricity supply paralyzed strategic public services such as Beirut International Airport (BIA), water filtration and pumping systems, ports and prisons.

The October 9, 2021, blackout was particularly impactful, as the shortage of petroleum derivatives also affected the private sector, leaving generators unable to operate.

Major importers, for their part, preferred to unload their cargo in Lebanon to benefit from Treasury-subsidized prices, only to then re-export it to Syria where they sold it at a high profit. The result: the Lebanese were cheated from all sides. The gradual return of electricity was only made possible through the intervention of the Lebanese Army, which tapped into its strategic fuel reserves, and with logistical support from the Tripoli and Zahrani oil facilities. Together, they helped deliver around 6,000 kiloliters of diesel to temporarily power the grid.

EDL’s Coffers Are Empty

The descent into darkness began to slow the day EDL’s chronic ailment was finally diagnosed. Priority one: replenish the empty coffers – a prerequisite for restoring the balance between skyrocketing demand (subsidized, thus, artificially inflated) and a dwindling supply – entirely dependent on an aging fleet of power plants in desperate need of overhaul. “The real turning point depends on market-based solutions,” said former Minister of Energy and Water Walid Fayad to This Is Beirut.

Ten days after taking office, he made a decision as unpopular as it was necessary: to raise electricity tariffs, which had been frozen for decades. He wasn’t new to the issue; in 2012, as a consultant at Booz & Co, he had worked on Lebanon’s electricity pricing under a mandate from the state. Notably, this move was preceded by another of his government’s decisions to eliminate subsidies on all petroleum derivatives.

Prices Up, Consumption Down

The gradual end of politically motivated electricity subsidies bore fruit: consumption dropped by 4 billion kilowatt-hours, resulting in savings of nearly $2 billion. The fuel import bill also fell from 8,000 to 5,000 tons per year. This marked a historic shift for EDL, which, for the first time in forty years, regained a semblance of financial health. Its treasury now exceeds $150 million, while outstanding customer receivables exceed $500 million.

This recovery allowed the public institution to catch up on some long-overdue actions: infrastructure maintenance, emergency investments, improved electricity supply (now available 8-10 hours a day), and even partial debt repayment – particularly to Iraq. All of this happened amid a budgetary drought, with public funding suspended by interim Central Bank Governor Wassim Mansouri. Still, according to Energy and Water Minister Joe Saddi, about $1.2 billion in debt remains outstanding to Iraq.

Electricity More Expensive, Renewables on the Rise

The upward revision of electricity tariffs – frozen since Rafic Hariri came to power – had a catalytic effect on the energy behavior of households and industry. Confronted with real costs, many turned massively to sustainable solutions, triggering a major shift toward renewable energy. In two years, installed solar and hydro capacity jumped from 150 to 1,500 megawatts, now covering 25% of national electricity demand. The removal of blind subsidies reestablished economic logic, making renewable investments not only viable but strategically sound across all sectors.

Inset: Solar Energy, a Strategic Pillar Losing Momentum

Energy Minister Joe Saddi aims to make solar energy a key axis of the sector’s recovery, based on an already established roadmap. According to him, reducing the cost of energy production is a top priority. This could be achieved by expanding the use of solar energy through the construction of power plants with capacities between 100 and 150 megawatts, alongside the creation of new gas-powered plants – a solution previously proposed by the late Energy Minister Georges Frem at the end of the Civil War.

On the ground, however, the market is clearly slowing. In 2024, Lebanon imported 2.24 million solar panels for $75 million – a 41% drop compared to 2023, and an 82% plunge from 2022, when imports reached 5 million panels worth $416 million. Residential demand began declining in early 2023, due in part to the stabilization of neighborhood generators, the end of the fuel crisis, and the widespread installation of electric meters. The drop is also explained by a lack of available rooftop space and market saturation: most households and businesses capable of investing have already equipped their buildings.

Faced with oversupply, prices have collapsed. The cost per watt fell from 47 cents in 2022 to just 10-15 cents in 2024 – a 79% drop. The average price of a panel dropped from $92 to $33 in two years.

Comments