The eight Maronite mummies from the Assi cave, below Hadat in the Qadisha Valley, revealed the medieval culture of the Maronites. They unveiled their art, artifacts, weapons, prayers and handwritten documents. The bodies seem to speak of their suffering and the fervor of their faith.

The medieval Maronite mummies buried in 1990 in the Assi cave, beneath Hadat, sparked the curiosity of the explorers from GERSL (Groupe d'Études et de Recherches Souterraines du Liban) regarding this troubled period in the second half of the 13th century. Ancient Maronite accounts, copied in the 17th century by Patriarch Estéphanos Douaihy, mention events resembling genocide. However, it is primarily the Bible of the Monastery of Mor-Aboun (now Saint-Antoine de Qozhaya) that recounts in detail the tragedy that took place in the Assi cave, where the population of Hadat had sought refuge.

The Cave

In various accounts, both Maronite and Mamluk, the cave is described as magnificent and compared to a fortress. It was said to be so inaccessible that Muslims had to besiege it for seven years and only conquered it through deception. Only after promising Aman (a guarantee of safety) to the inhabitants were they able to enter—after which they ravaged and burned the village and “took the women into captivity.”

However, research conducted by Fadi Baroudi questions the supposed seven-year siege, which seems exaggerated, and instead suggests a duration of several months. He also places the events around 1268, rather than 1283 as mentioned by Patriarch Douaihy.

According to Maronite tradition, it was Patriarch Daniel of Hadchit who was abducted during the Mamluk attack of 1283. But records show that he had already died in 1282. Was it then the schismatic Patriarch Luca of Bnohra—at odds with both his own Maronite Church and the Frankish hierarchy—who was present? In 1283, he was replaced by Jeremias of Dmalsa, with the support of Count Bohemond VII of Tripoli. This may explain Luca’s vulnerability despite the inaccessibility of his refuge.

The altitude of the cave is striking, and one wonders how an entire population, including children and the elderly, managed to reach it. How did they equip it with infrastructure for drinking water, with its ducts and cisterns—two in the shape of wells and one main reservoir still intact, measuring 3.5 meters long by 1.4 meters wide and 1.5 meters deep? Its capacity was therefore 8 cubic meters of water.

Although a millstone is missing, it appears that a basin was used to manually grind grain. Some parts of the cave are better sheltered than others—some higher, some brighter—but one distinct space stands out as the burial chamber.

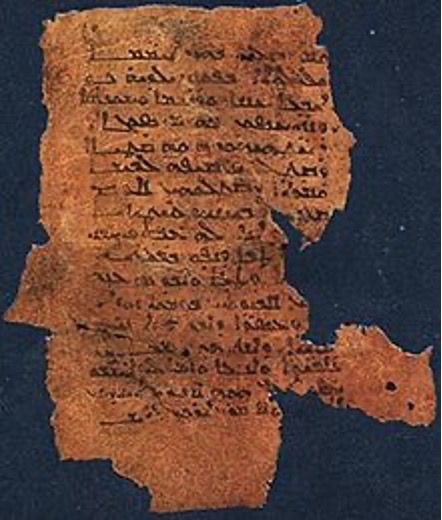

Praise to the Lord in Syriac language, Estrangelo script. (Photo GERSL)

Artifacts and Inscriptions

The burial chamber is a treasure trove of information, offering not only mummies, but also pottery shards, coins, textile fragments and over 20 medieval texts. Mamluk influence at that time is surprising—both in imported objects and in the use of Arabic by some Christian scribes. For example, a pottery fragment bears the name of its owner, Boutros of Hadat, in Arabic, and part of a text is signed by the archdeacon of Hadat, Georges, son of David.

Other texts and prayers found are in Syriac, which was the vernacular of Mount Lebanon and the official liturgical language of the Maronite Church. These inscriptions—found on clothing, belts or near the mummies—use both cursive (Serto) and monumental uppercase script (Estrangelo).

This juxtaposition of Syriac and Arabic is also evident in the coins found on site. Scattered across the area are 13th-century coins, some Crusader and others Mamluk. Also Mamluk in style is a double-toothed wooden comb.

One of the mummies, that of a woman, was buried with the wooden key to her house, symbolizing the extinction of an entirely wiped-out family. Elsewhere, a mother was buried with her 18-month-old child resting against her left shoulder.

The Arrows

Just like the texts and coins, the many arrows found at the site also display a juxtaposition of the Christian and Mamluk worlds. Many are of Mamluk craftsmanship, while others are clearly Maronite. The latter are particularly notable for using oiled paper fletching instead of traditional feathers.

One of these Maronite arrows was found completely intact—from the tip to the nock. Its paper, soaked in olive oil, helped maintain stability while reducing the drag typically observed with feather fletching. This discovery helped solve the mystery behind the fame of Maronite archers mentioned in medieval sources. On that note, Jacques de Vitry, recounting the story of Archbishop William of Tyre, described these men in the province of Phoenicia, near the city of Byblos… and called Maronites, as being primarily armed with bows and arrows and skilled in battle. Their renown thus seems closely tied to their unique arrow-fletching technique.

Mummy of Yasmine with cross-adorned garments and necklaces made of glass and coins. (Photo GERSL)

The Motifs

Textiles were found both on the mummies—as clothing—and scattered around the cave as fragmented remains. Made of thick cotton, the garments are embroidered with squares and diamonds, crosses and flowers, which strongly resemble the abstract designs of Armenian Christian carpets later adopted by the Turks and Kurds. As for the figurative imagery, it reflects the influence of Syriac illuminated manuscripts, decorated with animal and plant forms.

One such image depicts two peacocks facing each other on either side of a Tree of Life. This theme of mirrored animals, along with the tree or fountain of life, is typical of the Codex Rabulensis, the 6th-century Syriac Maronite Gospel Book that left a lasting mark on Maronite imagery and Christian iconography in general. Its abstract motifs of tiered patterns and its figurative themes were revived in the medieval frescoes, manuscripts and clothing of these Maronite mummies, who have crossed the ages to reconnect us with the suffering and richness of our past.

Comments