Since the Middle Ages, Lebanese builders have designed their churches with a deep awareness of the role of liturgical chant, shaping their architecture to enhance its resonance. The stone structure was not merely a place of worship but a medium for voice, music and chant, giving them a tangible form.

Syriac chant is inherently democratic. The Mass is a shared experience, a horizontal dialogue between the officiant and the congregation. Chant is both a form of prayer and a foundation of the liturgy, practiced and known by the entire community.

“In Syriac liturgical chant,” wrote the Benedictine Dom Jean Parisot in 1899, “everyone — priests, clerics, congregants and even children — can take part. Except for sections reserved for the officiant, the chants are sung by all who can read Syriac.” He added that even those who could not read still participated by memorizing the prayers and hymns.

The Rish Qolo

To make it simpler and more accessible, all chants follow a standardized verse structure known as rish qolo, the equivalent of the Greek hirmus. Qolo means both “voice” and “sound,” and the rish qolo serves as the main melody that provides the framework for composing hymns. At the beginning of a poem, one might find the phrase “according to the qolo of…” This served as a form of musical notation, indicating the melody to which the text should be sung.

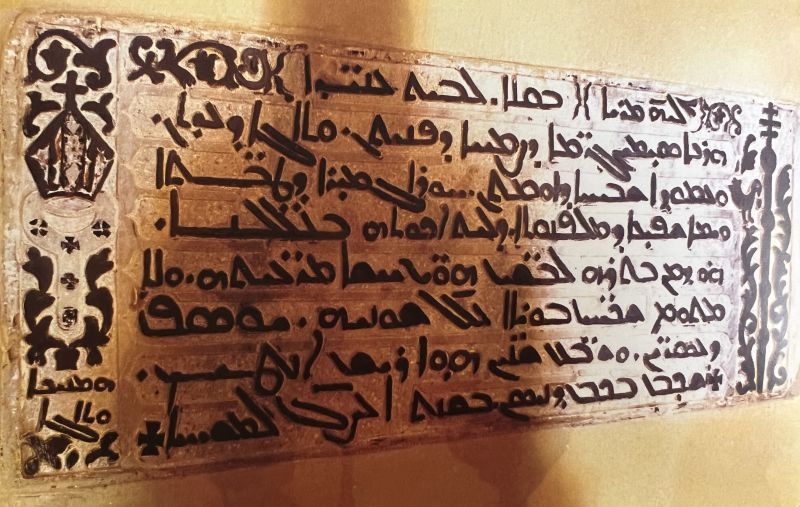

On the tomb of Patriarch Joseph Estéphane in Gosta, the opening of his epitaph reads "Qolo d’veit anidé." This indicates that the inscription below was meant to be sung to the melody of "d’veit anidé."

The Syriac culture the Benedictine scholar encountered was a living tradition. Instead of turning to specialized institutes or libraries, he sought it out in villages and their choirs. In the Qadisha region, in 1947, Jacques Fayad traveled to Hasroun, where he documented numerous chant notations. He later wrote, "Hasroun’s choir is the best in the community at perfecting Syriac melodies." He therefore chose to base his work on the melodies as they were known and practiced in Hasroun, a village widely regarded as a reference in this tradition.

Jacques Fayad even observed a distinct accent and tonal quality unique to the people of Hasroun. “This is evident in the first melody of Bkulhoun-Saphré, Yawmono, Hdaw-Zadiqé and Qadishat-Guér-Bashroro,” he noted. Highlighting this musical richness, he added, “I documented twenty melodies for the Bo'outo d-Mor Yaaqouv and seven for the Bo'outo d-Mor Éphrem — all widely known in Hasroun.”

The Typology

There are many variations of rish qolo. Therefore, the qolé (the plural of qolo) were categorized into several musical genres, based on their type. These include qolo pshito, which signifies the simple tone; qolo ashinto (or strong tone); qolo arikho (long tone); and qolo zeouro (short tone). There is also qolo nguido (attractive), qolo me'iro (awakening) and qolo piosto (inviting or convincing). Additionally, qolo yawnoyo refers to the Greek tone, qolo nousroto is a melodic tone and qolo afifo is a tone with two alleluia chants.

The Éphrémoyo is a heptasyllabic hymn written according to the meter of Saint Ephrem, while the Yaacouvoyo follows the meter of Saint Jacob of Sarug, consisting of do dodecasyllabic verses divided into three tetra syllabic phrases. The souguito is an eight-syllable hymn. The mimro is a didactic hymn in the style of Saint Ephrem and Saint Jacob, the great masters of Syriac versification. Finally, the madrosho is a hymn with a didactic purpose.

The syllabic structure of these hymns forms the rhythmic foundation of Syriac chant. It imparts beauty through simplicity. Restraint is key, conveying a distinctive mood of spirituality unique to Syriac Christianity and its theology.

The Rish Kipo

The eschatological dimension conveyed through austerity extends from the music to the space that embraces it. To a newcomer, the churches, strikingly barren of any ornamentation, might seem like the result of material or intellectual poverty. A single bell, suspended between two stones, scarcely sets this place of worship apart from the other modest cottages of the village. If a carved lintel emphasizes the significance of the entrance, it is only decorated with a cross or salvaged from the Phoenician temple on the site.

Yet, the technical prowess was undeniable. The austerity was deliberate, not a limitation. Intellectual brilliance was truly present, as demonstrated by the construction of the vaults. These vaults are filled with clay jars embedded up to their necks, leaving only the rims visible. The builders' understanding of acoustics is astonishing. Since the Middle Ages, they have continuously factored in the significance of their liturgical chant in the design of their churches and the evolution of their architecture.

Each jar is of a different size to absorb specific sound waves and eliminate the disturbances caused by echoes. The sound and resonance of instruments and voices were fundamental to the builders’ approach, prioritized above any decorative excess. The stone structure was designed to support the voice, music and liturgical chant, serving as their crystallization for these elements. This style of architecture could be referred to as rish kipo (the cornerstone), which captures the voice and allows the rish qolo to unfold in all its variations.

Syriac chant transforms the Mass into a theatrical performance. Its beauty lies in the balance of restraint, variety and the democratic participation of all. Patriarch Estephanos Douaihy explains that the Mass was structured with a harmonious blend of prose and sung poetry, ensuring vitality and preventing monotony. He wrote that "to prevent the congregation from growing weary of its length and the clergy from singing continuously, the glorious Fathers ordained that the qolé (chants) be interspersed with the marmyoto (prose) and supplemented with the psalms, as instructed by the holy apostles."

Comments