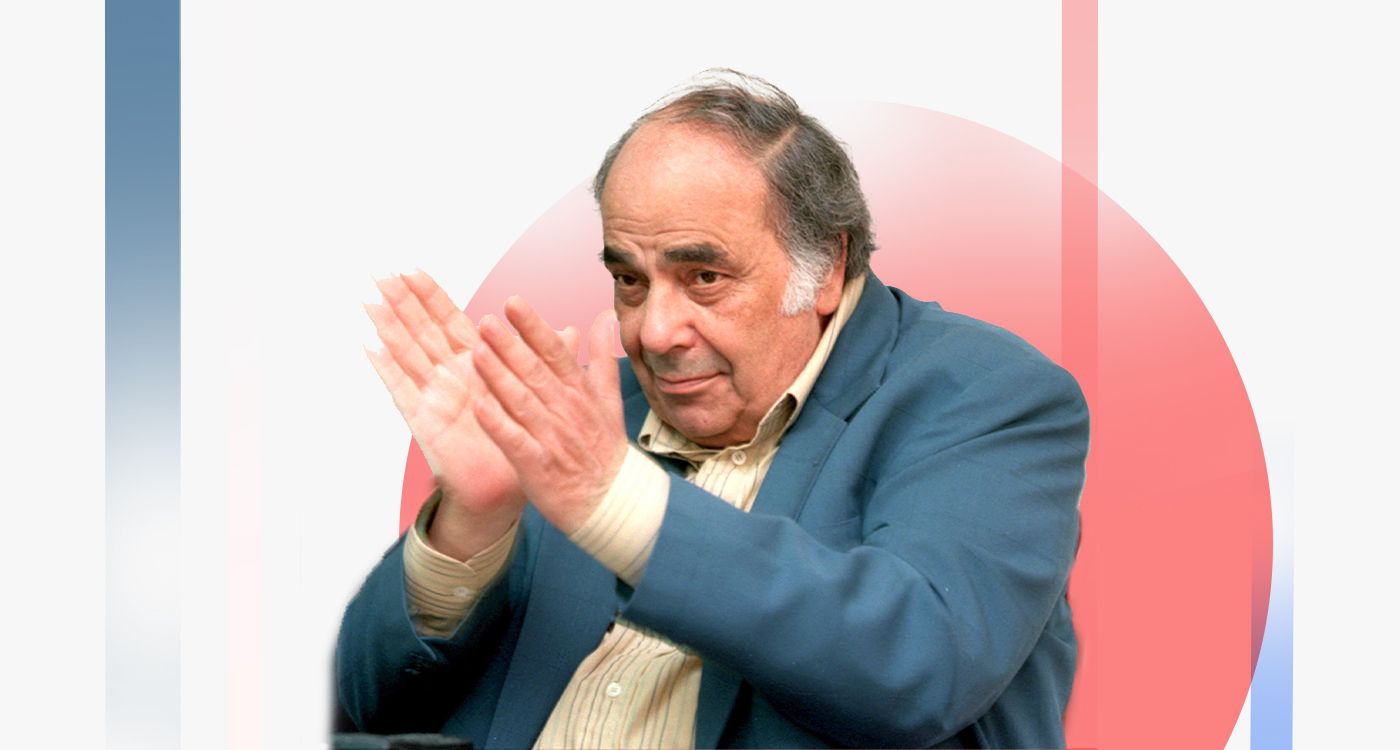

On the centenary of Mansour Rahbani’s birth, we not only honor the collective journey he shared with his brother Assi but also the legacy he carried forward alone after Assi’s passing in 1986. He perpetuated their artistic vision, shaping what became known as "Lebanese music" and solidifying its influence on the Arab music scene. Let us take a closer look.

They were two—two distinct minds, two creators, two independent intellectuals. Yet an artistic symbiosis united them, rendering their names inseparable: the Rahbani Brothers. Composers, poets, and thinkers, they merged their visions without overshadowing one another. Assi and Mansour—one could not exist without the other. The poet gave form to the soul’s abstraction, and the composer transformed it into sound. Through this constant dialogue, where poetry nourished music and music exalted poetry, their art was born. Brothers by blood and spirit, they gave voice to a nation in perpetual search of itself. Over decades, they built a repertoire that merged various musical traditions, identity-driven visions, and reflections of socio-political upheavals.

Today, Lebanon remembers Mansour (1925–2009), a century after his birth, following the 2023 centennial celebration of Assi (1923–1986). This century-long legacy invites reflection on the musical and cultural heritage of a country in continuous construction of its identity.

Musical Transculturation

Born into a modest family in Antelias, the Rahbani brothers did not inherit music from their parents; they conquered it themselves. Orthodox Byzantine church music and Maronite liturgical chants deeply shaped their auditory and spiritual sensibilities from childhood, while Western classical music opened their imagination to infinite possibilities. After the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the French Mandate in Lebanon, native Levantine modal monophonic musical practices clashed with the European harmonic tonal system, which was imposed as a model of "modernity." Furthermore, the 1910 opening of Dar al-Mousiqa—later to become the National Conservatory of Music—by Wadih Sabra (1876–1952) marked the beginning of a Westernization of musical education and traditional practices in Lebanon, as noted by Lebanese historian Diana Abbani in a 2019 study.

Bertrand Robillard, co-founder of the Lebanese Academy of Fine Arts (ALBA), trained the Rahbani brothers in Western harmony, counterpoint, and fugue. Armed with this education, Assi and Mansour later laid the foundations of the Arab polyphonic movement—an attempt previously initiated but left unfinished by Toufic Succar (1922–2017). Their encounter with Fairouz, then a young chorister at the national radio, marked the beginning of an artistic adventure that would redefine the Arab musical landscape, previously dominated by Egyptian influences.

In pre-war Lebanon, their work was shaped by a rapidly transforming country. Their operettas and compositions captured the aspirations of the youth at a time when Lebanon epitomized cultural pluralism. Over the decades, they developed a hybrid musical language, blending Levantine musical heritage with Western harmonic principles. This hybrid aesthetic was seen by some as the model upon which "Lebanese music" should be built.

A Space for Reflection

Then came the so-called civil war. The narratives of the Rahbani brothers' songs took on a new tone—one filled with nostalgic nationalism, pain, but also hope. While Fairouz’s voice remained the privileged instrument of this musical memory, it also conveyed an inner exile—a deep wound that resonated far beyond Lebanon’s borders.

After Assi’s death in 1986, Mansour carried on alone, ensuring the continuity and evolution of a legacy he now bore independently. By then, the artistic separation between Fairouz and the Rahbani family had already been finalized. "After Assi’s passing, Mansour shifted towards creating larger, more elaborate works, with increasingly sophisticated librettos and a stronger emphasis on dramatic singing," explains composer Oussama Rahbani, Mansour’s son. "His theatrical pieces also became more complex in staging, adopting a continuous narrative cycle rather than incorporating songs as standalone elements, as was the case in their earlier works."

From the late 1980s until his death, Mansour composed a significant number of musical works, particularly theatrical pieces, which gained lasting recognition both for their longevity and cultural impact. "His plays ran for months, sometimes even years, far longer than the earlier works of the Rahbani Brothers," says the Lebanese musician.

Among these were Saif 840 ("Summer 1840", 1988), Al-Wasiya ("The Testament", 1994), Akher Ayyam Socrate ("The Last Days of Socrates", 1998), and Wa Qama Fi Al-Yawm Al-Thalith ("And on the Third Day He Rose Again", 2000), in which Oussama collaborated with him on an avant-garde theatrical approach. He later composed Abu Tayeb Al-Mutanabbi (2001), Moulouk Al-Tawaef ("The Kings of the Sects", 2003), Hokm Al-Roayan ("The Reign of the Shepherds", 2004)—which eerily foreshadowed the political events of 2005 to 2008—followed by Zanoubia ("Zenobia", 2006) and Aawdat Al-Finik ("The Return of the Phoenix", 2008). "In 2000, he also composed a Maronite Mass," he adds with pride.

The Disillusionment of the Arab World

Mansour Rahbani’s work thus evolved into a space for reinvention, where theatrical art took on a more pronounced socio-political dimension. He transformed musical theater into a critical reflection on history and the disillusionments of the Arab world, embodying a form of cultural resistance. "His creative horizons expanded considerably. He was no longer as focused on songs, even though he continued composing them. Times had changed, and if Assi had been alive, he would have certainly followed the same path, as they both constantly sought innovation," asserts his son.

Additionally, classical music (in the Western sense) held a special place in the Rahbani brothers’ artistic vision, particularly for Mansour. "He had a deep appreciation for music that evoked nature, particularly Ravel’s impressionism, as well as the romanticism of Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff. Stravinsky’s influence is especially evident in Jibal Al-Sawwan ("The Flint Mountains", 1969), with passages reminiscent of Petrushka (1911), while echoes of Stockhausen can be heard in the introduction of Al-Baalbakiya ("The Baalbek Woman", 1961). Not to mention the sonic imagination of Mahler," he explains.

While the musical productions of the Rahbani Brothers and Fairouz were largely rooted in Lebanon and Syria, Mansour Rahbani’s works reached stages across the Arab world. In this regard, Oussama Rahbani bluntly states, "I don’t know why the Arab countries neglected the Rahbani Brothers and Fairouz."

Regardless, history will always have the final say, and it will undoubtedly be in favor of these visionary artists who left an indelible mark on humanity. Through the power of their talent and the modernity of their vision, Assi and Mansour Rahbani secured their place in the pantheon of great Arab creators. Today, Mansour’s centennial offers a valuable opportunity to reignite this legacy and celebrate a heritage whose brilliance continues to inspire.

Comments