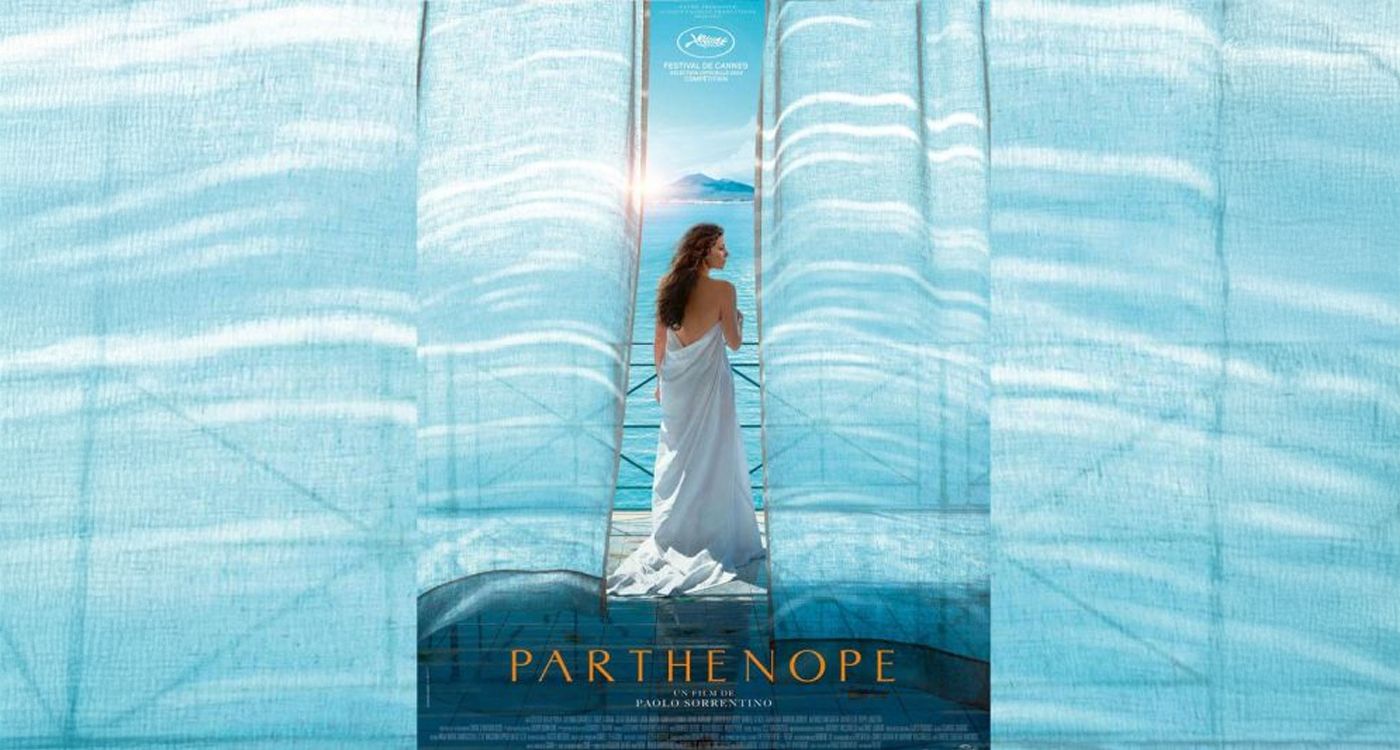

With Parthenope, Paolo Sorrentino crafts a mesmerizing visual tribute to Naples, his hometown. Through the fate of a mermaid-like woman, the Italian filmmaker weaves a sensual and melancholic fresco on beauty, the passage of time and a mythical city where splendor and decadence coexist. While the title of this chronicle nods to Vadim, what emerges here is an authentically Sorrentinian work, marked by his unique vision and instantly recognizable aesthetic language.

After glorifying Rome in The Great Beauty, Paolo Sorrentino returns to Naples for an aesthetic and sensory journey into the heart of his birthplace. Parthenope is a declaration of love, a mythological celebration and a reflection on beauty—both a burden and a privilege. Each meticulously crafted shot turns Naples into a character in its own, mirroring its eponymous heroine. A city of extreme passions, Naples enchants or repels, but never leaves one indifferent. Once under its spell, no other city can replace it, as it exerts an irresistible pull—just like its legendary siren. The story begins in 1950, in a sumptuous seaside palace. A child is literally born from the waters, a modern incarnation of Parthenope, the stranded siren who supposedly gave her name to the city. From the moment of her birth, myth and reality become intertwined. She grows up in a joyful family, cradled by carefree days, falling asleep in a royal carriage before blossoming into a woman of breathtaking beauty.

The Siren and Her City: Intertwined Fates

Sorrentino dwells less on Parthenope’s childhood and focuses instead on her life as a young woman, sublimely portrayed by Celeste Dalla Porta. In her first film role, the actress commands the screen with a magnetic, almost otherworldly presence, captivating at every turn. Her bewitching beauty draws people to her irresistibly. Yet, reducing Parthenope to her looks would be a mistake, and Sorrentino knows it well. His heroine, armed with sharp intelligence and insatiable curiosity, chooses to study anthropology—the mythical creature seeks to understand humankind. The tension between her extraordinary beauty and her quest for meaning runs throughout the movie. Sorrentino’s signature direction reaches new heights of virtuosity in this film. His camera caresses both bodies and architecture with the same sensuality, exalting the Neapolitan light. This deeply Mediterranean vision of beauty gains deeper significance as the audience watches Parthenope transcend mere desirability, fully aware of the effect she has on others and, at times, wielding her beauty as both a weapon and a curse. The narrative unfolds in tableaux, following the rhythm of the seasons and the ages of life. As Parthenope matures, Naples evolves alongside her, yet retains its soul—forever torn between grandeur and chaos.

Neapolitan Paradoxes: Between the Sacred and the Profane

Sorrentino asserts a vision of Naples uniquely his own, far from the usual influences of Visconti or Fellini. His gaze shifts between opulence and rawness, the sacred and the mundane, without ever falling into nostalgia or imitation. His cinema has often been linked to past Italian masters, but that is not the point of this film. This chronicle seeks to credit Sorrentino with what is truly his: a singular style and a visual language that owes nothing to anyone but his own sensibility.

One of the film’s most striking sequences embodies this distinct approach: a meeting with the son of an anthropology professor, hidden from the world by his father due to his monstrous, elephantine, almost Buddha-like appearance. This surreal scene unfolds as a grotesque ritual where the sacred and profane intertwine, reflecting the deep contradictions of Neapolitan society.

Another iconic sequence shows Parthenope adorned with the treasures of San Gennaro. Seeing this mermaid-woman, nude yet draped in jewels more precious than the British crown, while poverty reigns in the surrounding neighborhoods, encapsulates the paradox of Naples. These relics, displayed for admiration, this sacred blood that refuses to liquefy—the long-awaited miracle that does not come—form a powerful metaphor for unfulfilled hopes and the unwavering faith of a city. Through these symbol-laden tableaux, Sorrentino paints a striking mosaic of Naples, capturing its traditions, excesses and untamable energy.

In her later years, Parthenope is played by Stefania Sandrelli, a legendary figure from the golden age of Italian cinema. With infinite grace, she embodies an aging Parthenope, imbued with the history of Naples, carrying its entire memory within her.

The original soundtrack, another hallmark of Sorrentino’s cinema, draws from a nostalgic repertoire featuring artists like Riccardo Cocciante, Gino Paoli and Marino Marini. These melodies underscore the film’s deeply Italian essence. Parthenope exudes undeniable visual elegance, as refined costumes dress the characters in discreet sophistication. This artistic direction enhances the film’s overall aesthetic, which, if it were mere decoration, might have been its greatest flaw. However, it serves a deeper purpose—exploring beauty as both a blessing and a curse.

Beyond its contemplative nature and visual perfection, Parthenope questions our relationship with beauty, in both people and places. Beauty that brings misfortune, that becomes a weapon against oneself and others. Like Naples—sublime and chaotic—the heroine is a bundle of contradictions: both seductress and intellectual, frivolous and profound, passionate yet detached. She consumes men like she smokes her cigarettes, never truly attaching herself—perhaps because, deep down, she knows she doesn’t quite belong to their world.

If Parthenope inevitably divides audiences—between those unmoved by its stylization and those seduced by its mesmerizing charm—it is precisely because Sorrentino does not seek consensus. His cinema, like Naples and like his heroine, is excessive, baroque and unrestrained. He invites us to dive into a total sensory experience where beauty is not mere ornamentation, but the very subject of the work.

Through the life of a water-born woman from youth to old age, Sorrentino also tells the story of Neapolitan society—its grandeur and its horrors, its vitality and its decadence. The film does not aspire to be a sociological documentary on Naples, but rather a love letter to a city-woman, a woman-city, in all their complexity and fascination. As Parthenope herself puts it, in a line that encapsulates the film’s essence, “I was sad and frivolous, determined and lazy, like Naples, where there is always room for everything. I was alive and alone.”

Comments