The Codex Rabulensis is the oldest illuminated manuscript with a precisely confirmed date, serving as a critical reference for dating other Christian works that lack colophons indicating their creation. This Syriac Gospel book has crossed over centuries, from the Monastery of Saint John in Beit-Zogba to the Maronite Patriarchate of Ilige, then to Qannoubine, and finally to the Medici Library in Florence.

This manuscript is among the most significant treasures of global Christian heritage. Dated to the 6th day of Shevot (February) in the year 897 of Alexander (586 AD), as explicitly stated in its colophon, the Codex is a cornerstone for art history. It offers invaluable insights into the Christian artistic tradition, both in the East and the West.

An Artistic Treasure

The Codex serves as a benchmark for dating manuscripts from all Christian traditions. Its style, iconographic program, portrayal of figures and composition of subjects have profoundly influenced subsequent Christian art, including illuminations, icons and large frescoes.

While it may not be the oldest illuminated manuscript, it is the earliest with a confirmed date. Armenian, Greek, Latin, Coptic and Syriac works lacking dated colophons are chronologically anchored using this invaluable reference.

The Codex Rabulensis is a complete manuscript containing 292 folios, written in two columns of twenty lines each. Measuring 33 cm by 25 cm, it is a Tetraevangelion composed in Syriac, inscribed in monumental square Estrangelo script. As early as the 6th century, it laid the foundations for a Christian iconographic tradition embraced by both the Eastern and Western worlds.

Origin

The Syriac monk Rabula led the team of artists who worked on this masterpiece. He dated and signed the colophon, also recording its origin: The Mor-Yohanon (Saint John) Monastery of Beit-Zogba, likely situated in the Antiochene region, where Syriac and Hellenistic cultures intersected.

In the Middle Ages, the Codex resurfaced at the Maronite Patriarchal Seat of Our Lady of Ilige in Mount Lebanon, possibly passing through Kfar-Hay. By 1441, following relentless Mamluk raids, the patriarchal seat moved to Our Lady of Qannoubine, along with its library and archives. The Codex remained there until it was transferred to Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries through expeditions by scholars of the Maronite College in Rome. Today, it is preserved at the Laurentian Medici Library in Florence (Laur. Plut. I,56).

In the 18th century, Étienne Évode Assemani, a scholar from Hasroun, analyzed the Codex, providing Latin translations and interpretations. This work laid the foundation for the manuscript and other Eastern works, which he personally transported to Italy, where he organized and catalogued them.

The manuscript’s historical value is further enriched by its marginal notes, added in later centuries. On pages written and illustrated in 586, successive Maronite patriarchs inscribed additional texts during the Middle Ages. These notes, spanning centuries and languages (from Syriac to Garshuni), mention six patriarchs, including Daniel III of Hadshit (1278-1282), Jeremiah III of Dmalça (1282-1297), John XI of Gege (1404-1445), Jacob III of Hadat (1445-1468), Peter VI of Hadat (1468-1492), and Simeon V of Hadat (1492-1524).

Iconography

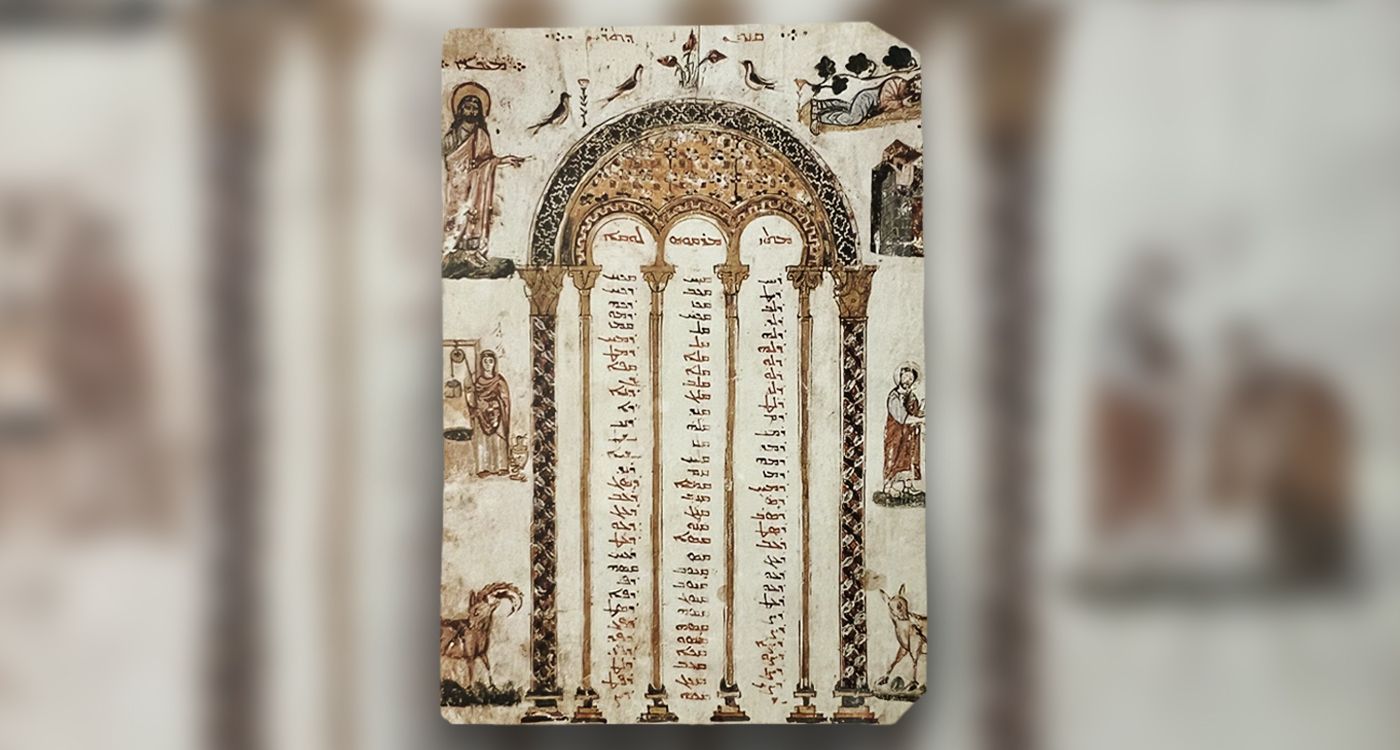

The Codex Rabulensis features pages dedicated to the Syriac text of the Gospels in its simple form, known as Pshitto (or Peshitta). The illustration folios prominently include the Canon Tables as the central element of their composition. Along the central margins, vignettes depict key episodes from the life of Christ. Meanwhile, the upper and lower margins are adorned with an extraordinary array of animal and plant motifs, making the Rabulensis a unique manuscript of its kind. Such decorative abundance would only reappear in Armenian art of the 12th century, as Byzantine painters used similar practices only sporadically between the 9th and 10th centuries.

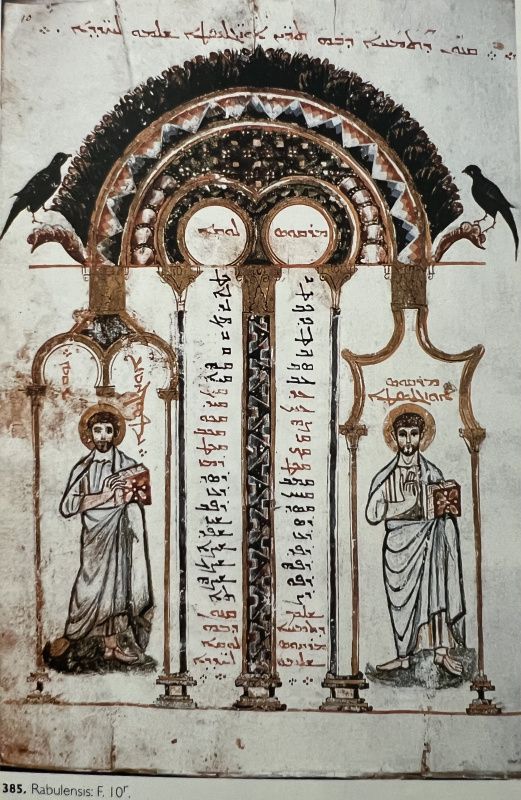

The Codex Rabulensis contains twenty-six illustrated folios, showcasing either Concordance Canons or large compositions that fill entire pages, evoking the grandeur and aesthetic of frescoes.

Codex Rabulensis, folio 10 R°, Concordance Canon with two arcades. © Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana

Arcades

A series of arcades on slender columns adorns the pages of the Rabulensis. This design was used both for depicting figures and for the numerical lists that indicate the correspondences between passages in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. It was Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea who conceived the idea of placing the numbers alongside their counterparts, creating what came to be known as the Canon Tables or Concordance Tables.

Concerning narratives shared by two evangelists, the composition features two arcades. Events recorded by all four evangelists are represented with four arcades. The most common concordance, involving three evangelists, uses a triple arcade. This design, rediscovered in the 18th century by Étienne Évode Assemani and the Maronite College of Rome, later influenced Lebanese architecture with its triple arches.

The symbolism of these arcades takes on a distinctive significance in the figurative compositions. The characters are isolated within this architectural framework, placing them in a timeless space beautifully described by Jules Leroy in his work Les Manuscrits syriaques à peintures, published by the French Institute of Archeology in Beirut. For Leroy, the sacredness sheltered by the arcade, which imbues “man with a new dignity by placing him in a separate realm that elevates him above the ordinary, justifies its use in the Canons to highlight the excellence of the sacred text, for which it serves as a solemn portico.”

This style of representation, which includes both portraits and the numerical lists of the Canons, became the stereotype for mosaics, frescoes, manuscripts and icons. It can still be found today in the frescoes of both traditional and modern Maronite apses.

Comments