Applying Article 113 of the Code of Money and Credit -which clearly stipulates that if Banque du Liban incurs losses, they must be covered by the Lebanese Treasury, without specifying the amount or the currency- is the only way to restore trust in the financial system and revive the economy.

The fate of depositors’ funds lies at the heart of Lebanon’s financial crisis. It is not merely a matter of figures or balance sheets; it directly affects the lives of thousands of families and undermines the country’s overall economic stability. Amid the ongoing financial collapse and the sharp erosion of the national currency’s purchasing power, the so-called “Gap Law” has emerged: a framework designed to determine the scale of losses within Lebanon’s financial system and distribute them among the state, the banks, and Banque du Liban.

On one hand, the law seeks to clarify responsibilities; on the other, it aims to establish a legal framework to address the deepening crisis. Yet its impact on depositors and the banking sector remains highly contentious, particularly amid accusations that it sidelines depositors’ rights and places the burden of the crisis squarely on their shoulders. The law has thus sparked heated debate over financial justice, public and private property rights, and the state’s ability to protect citizens’ savings at a time when Lebanon’s economy is facing unprecedented challenges on all fronts.

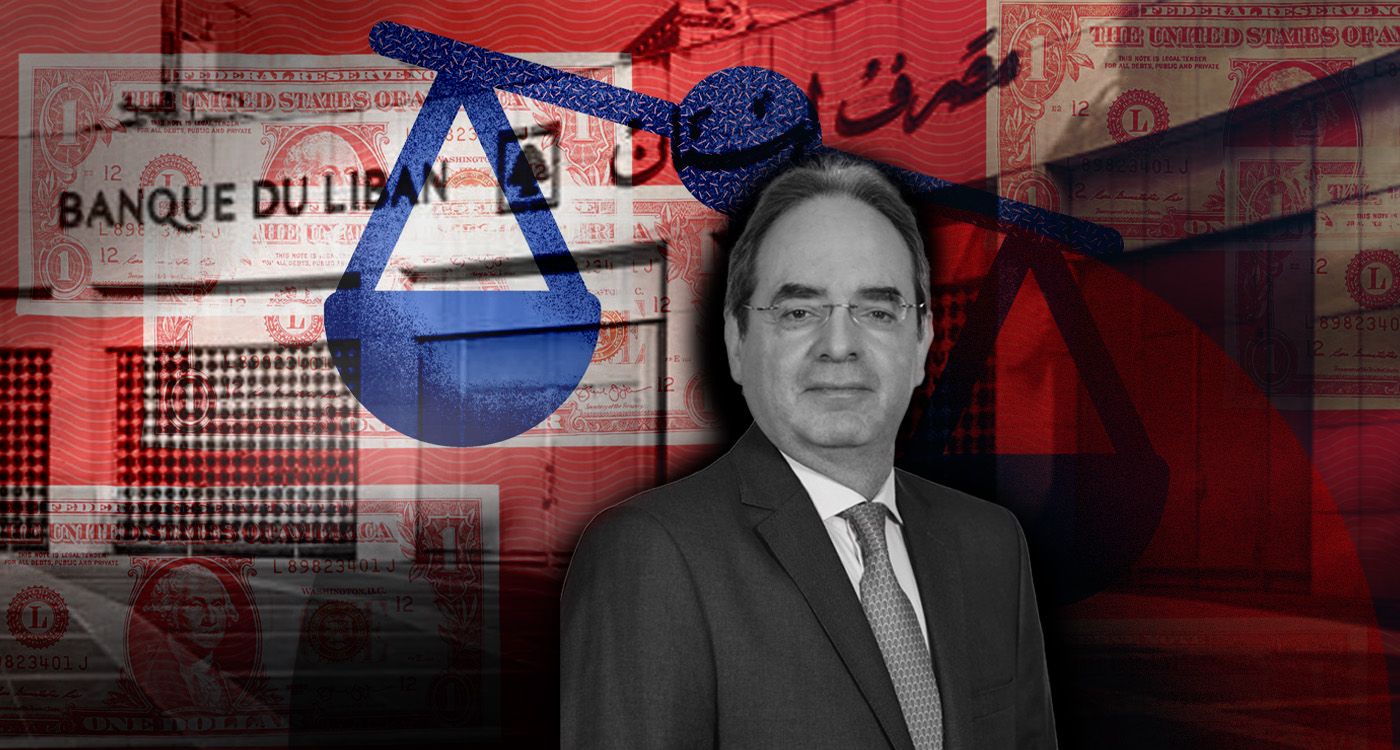

According to Nassib Ghobril, chief economist and head of research at Byblos Bank, any law determining the fate of deposits should have one primary objective: restoring trust in the economy and generating a positive shock for Lebanon’s financial system. However, the draft known as the Gap Law, as currently circulated, falls short of these goals and does little to rebuild trust or effectively support the economy.

Ghobril notes that what is happening today contradicts the narrative promoted earlier this year, when responsibility was said to be shared among the state, Banque du Liban, and commercial banks. In reality, the draft law assigns no responsibility whatsoever to the state, as if the Lebanese government were merely an external observer, mistakenly informed of a crisis unfolding elsewhere, rather than a central actor in what is happening on the ground.

As a result, Ghobril argues, the depositor is left to shoulder the burden alongside the banks, especially those with balances exceeding $100,000. The law imposes losses on banks beyond their capacity to absorb, potentially pushing some toward bankruptcy. Should that happen, depositors would lose a substantial portion of their funds and recover only minimal amounts, mere scraps of their savings.

Ghobril further warns that enforcing this law would encourage some banks to exit the market altogether, effectively handing the situation over to Banque du Liban. Since the onset of the crisis, the easiest option for banks would have been to declare bankruptcy and turn to the central bank, which would liquidate their assets and return only a small fraction of deposits to customers. Yet no bank has taken that step so far, and the sector has continued operating, thereby preserving depositors’ funds and rights. If, however, banks are forced into liquidation under the proposed law, depositors would recover only a very limited portion of their money.

Criticizing this trajectory, Ghobril says, “It seems that some parties are promoting an approach as if they do not want Lebanon to have a strong banking sector, portraying growth as possible without it, based on various theories. In practical terms, this means they do not want banks. In that case, Lebanon will remain trapped in a cash-based, shadow economy, estimated at around $6 billion, and will stay on the EU’s grey list and among high-risk countries.”

For Ghobril, the core demand is the application of the Code of Money and Credit. He points out that Article 13 stipulates that commercial banks’ placements at Banque du Liban are considered commercial debts, obligations owed by the central bank to commercial banks. Therefore, he argues, it is misleading to label the problem a “financial gap,” as if Banque du Liban had squandered the money recklessly or gambled it away. The reality, he stresses, is different: it was the state that squandered billions, whether on electricity or on the cost of maintaining a fixed exchange rate, as acknowledged in every ministerial statement issued over the past 30 years, up until 2018.

Ghobril also underscores the importance of applying Article 113 of the Code of Money and Credit, which clearly states that if Banque du Liban incurs losses, they must be covered by the Lebanese Treasury, without specifying the amount or the currency. Implementing this provision, he says, is essential to restoring trust in the financial system and reviving the economy. Responsibility must be borne by all three parties, starting with the Lebanese state; otherwise, exiting the crisis, rebuilding trust, and reactivating the banking sector in an effective manner will remain extremely difficult.

The law remains stalled in the Cabinet and is expected to be referred to Parliament for a vote, an unlikely prospect given the approaching parliamentary elections and the growing protests by depositors who oppose a law that would write off part of their savings. Such measures, they argue, constitute a clear violation of the principle of private property, the Lebanese Constitution, and the most basic standards of justice.

Comments