A soldier who understands war, Lebanon’s president must now prove he understands peace.

In early November 2025, Israeli bulldozers began erecting a concrete wall on Lebanese soil—a seven-meter-high scar from Maroun al-Ras to Aitaroun—cutting through farmland, razing homes, and casting a shadow over what remains of Lebanon’s sovereignty. Israel calls it “defensive fortification,” while Lebanon calls it “occupation.” But beyond definitions lies a harder truth: this wall went up after Hezbollah dragged Lebanon into a war it never declared.

When Hezbollah opened the front with Israel in October 2023 “in solidarity with Gaza,” it presented the move as a moral duty. But that decision—unilateral, uncoordinated, and beyond state authority—became the pretext Israel needed to re-enter Lebanon, fortify border hilltops, and now build permanent structures on our territory. In the name of resistance, we have lost land.

Today, tens of thousands of Lebanese are displaced from their southern villages. The border towns that once symbolized steadfastness are becoming uninhabitable gray zones. And the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF), the sole legitimate defender of this country, is left patrolling the ruins of sovereignty stripped from it by both sides.

The wall does not just divide Lebanon from Israel; it divides Lebanon from itself. It separates those who still believe in a state from those who see militias as the state. It exposes the absurd equation that has trapped the country for decades: “Resistance before sovereignty.” But resistance without sovereignty is an illusion, a performance that leaves others to rebuild what its heroics have destroyed.

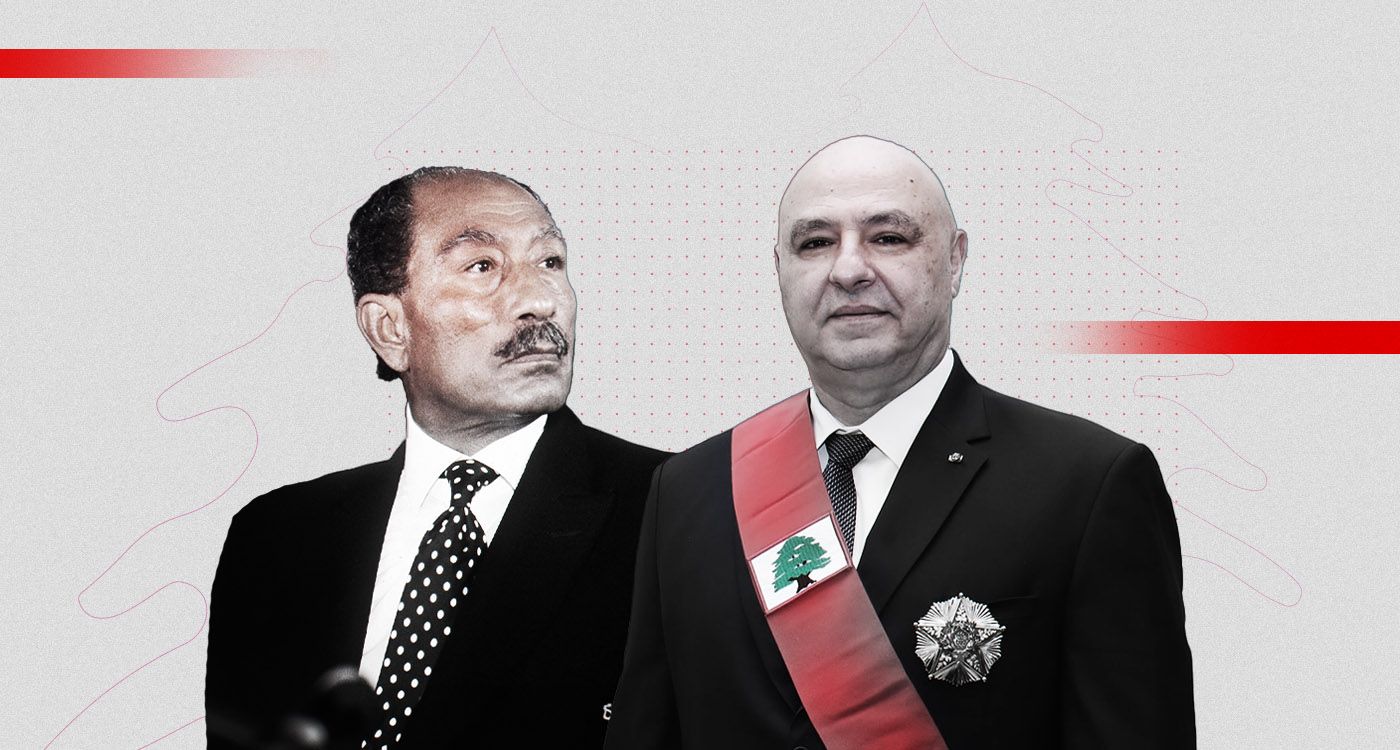

Half a century ago, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat faced a similar dilemma. Egypt had fought bravely in 1973 but remained trapped in poverty and partial occupation. Sadat shocked the Arab world by flying to Jerusalem in 1977. He addressed the Knesset and declared, “I came to build peace on the land of peace.” It was not surrender; it was strategy.

Sadat secured the full withdrawal of Israeli forces from Sinai, billions in reconstruction aid, and a permanent seat for Egypt at the table of nations because he understood one timeless rule: a leader who takes initiative shapes history; one who waits becomes its victim.

Lebanese President Joseph Aoun faces his own Sadat moment. A soldier who understands war, he must now prove he understands peace. Aoun has already urged the international community to pressure Israel to withdraw from occupied Lebanese territory, but the world barely listens. Why? Because Lebanon speaks with too many voices. One demands diplomacy, another fires rockets.

The world cannot take seriously a state that cannot speak for itself. The lesson from Sadat is simple: initiative changes perception. Egypt’s enemies called him reckless until he forced them to treat him as a statesman. Aoun must do the same, turning Lebanon from a passive victim into an active negotiator. That means launching an independent diplomatic offensive:

- Demand verified Israeli withdrawal under UN supervision.

- Tie peace to reconstruction and refugee return.

- Offer a phased integration of Hezbollah’s defensive units into the national army.

- Invite international guarantors—France, the U.S., and Arab partners—to enforce the deal.

This is not naïve idealism; it is national recovery. True patriotism begins with honesty. The occupation of Lebanese soil today is not just an Israeli act. It is also the consequence of a Lebanese faction’s decision to hijack the state’s war-and-peace powers.

Hezbollah’s “solidarity with Gaza” may have been emotionally noble, but strategically it was disastrous. It turned Lebanon into a secondary battlefield and handed Israel every justification for a long-term military presence. Acknowledging that is not an act of betrayal. It is the first step toward reclaiming what is left of the Lebanese republic.

Reports from multiple outlets warn that Israel’s new wall in southern Lebanon may be more than a temporary fortification. Far-right Israeli groups have already begun openly calling for the “conquest and settlement” of southern Lebanon, while settler organizations have advertised “properties” near the Blue Line, signaling ambitions far beyond security along the border.

Analysts now caution that Israel’s entrenchment on Lebanese soil, justified under the banner of “defense against Hezbollah,” risks evolving into a creeping annexation, hilltop by hilltop, wall segment by wall segment, outpost by outpost. If Lebanon remains frozen in political paralysis, these “temporary” outposts could soon become facts on the ground, as happened in the West Bank.

The warning is simple and urgent: either the Lebanese state acts now—diplomatically, militarily, and legally—or we will watch the border shift in silence and the south slip away piece by piece.

The wall at Maroun al-Ras is not just a barrier: it is a message, “Your sovereignty is negotiable.” If Lebanon continues to outsource its wars and delay its diplomacy, that message will become permanent, etched in concrete and silence.

Sadat once said, “The most dangerous thing we can do is wait.” He was right, because while others waited, he redrew the map. History is asking: will Lebanon keep dying in other people’s wars, or dare to live in its own peace?

Comments