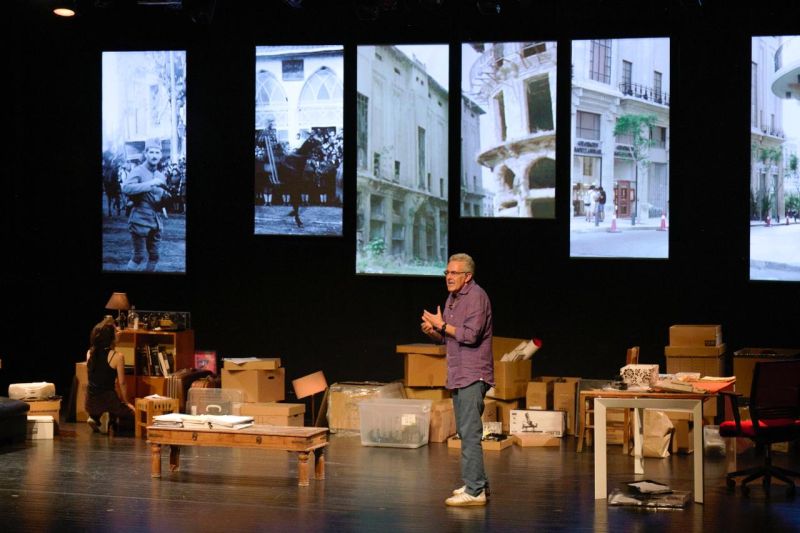

On the stage of the Monnot Theatre, Philippe Aractingi delivers a one-man show of rare intensity. In a fragmented and generous monologue, he exposes the wounds, memory and fragility of a Lebanese generation searching for grounding.

Attending “Sar wa’et el-haki” (It’s Time to Talk), Philippe Aractingi’s solo performance, is to dive headfirst into a whirlwind of memories, languages and emotions. The show, staged at the Monnot Theatre from September 30 to October 12, 2025, in Beirut, after a notable tour in France, Germany and Tunisia, was directed by Lina Abyad.

Philippe Aractingi delivers a one-man show of rare intensity. © Imad al-Khoury

This adventure began out of necessity: cinema had become inaccessible or too expensive to produce in Lebanon’s current context, forcing the director to seek other forms of expression. Frustration, urgency to bear witness and need to prevent memory from dissolving into silence became the driving forces behind this live performance. It was essential to tell the story, even without a camera.

From the first moments, the stage opens like a mirror in which Aractingi, alone, multiplies his voice, doubles, fragments himself to better find himself. Far from a linear narrative, a mosaic unfolds where his childhood intersects with that of hundreds of thousands of Lebanese, where his memories mingle with those of parents, children and even multiple generations touched by inner exile.

The stage design reinforces this fractured memory: scattered objects, boxes, memories piled or abandoned as in yet another relocation. What to take, what to leave behind, at every departure, every new storm? Aractingi leaves the question suspended in the theater air as it is in Beirut’s. Life sometimes seems to hinge on this brief hesitation, this doubt, this disorder, so familiar yet intimate. We laugh at the chaos, then choke up. The story of wounds and broken ambitions, serial relocations, separations, losses, pieces of oneself scattered to the winds, but also fleeting joys, surprises us. The happiness he evokes is as ephemeral as a butterfly flying under the shadow of an eagle! (A nod to one of his scripts still on paper.) Yet hope… always hope… pierces through the melancholy.

The play is structured in five parts, each marked by an audio tape. © Imad al-Khoury

The Stage as Catharsis

The play is structured in five parts, each marked by an audio tape, five magnetic tapes rescued from the past, each a chapter. One hears the father’s voice, the mother’s, their familiar accents ringing like a lullaby or a prompt: “Philippe, practice your scales…”

These tapes, carefully preserved, become the backbone of the journey, materializing the intrusion of the past into the present. Childhood memories resurface through projections, bits of Super 8 film, photos taken by Aractingi himself: fragile traces torn from oblivion, laid out as proof that everything can disappear, and what can be saved from oblivion must be saved.

War is never far away. Whether civil or otherwise, it looms, creeps in, resurfaces. Aractingi tells it without pathos, in simple language where French, Arabic and English intertwine, twist, and reinvent themselves. He invites the audience to dive into this linguistic whirlwind typical of Lebanese people, that strange mix that defines them. Just as one can feel (often) a stranger at home while loving this land viscerally. One wants to flee to forget, yet nothing is forgotten. Beirut continues to be told, over and over, even if the necessary perspective, the step back needed for true remembrance, has never fully happened. And rightly so: war is never over.

A live therapy session where laughter, tears and childhood flavors meet on stage. © Imad al-Khoury

The stage becomes an open-air therapy session. Child and adult search for each other, clash and perhaps eventually reunite through finally liberated speech. Aractingi dares to speak of his dyslexia, clumsiness, mistakes, doubts and laughter. This unease of belonging to no language, of never having a true home, gradually dissolves into acceptance and self-mockery. One understands why he photographs everything that moves him in Beirut: everything can disappear, five cities already erased, a sixth barely emerging. When you love, you stop counting. Yet each one of us counts differently, depending on the generation one belongs to, depending on what one remembers.

The play embodies the full complexity of Lebanon: memory refusing oblivion, violence mutating but never dying, tenderness surfacing amid turmoil. On stage, Philippe’s personal memories become those of a people, invoking collective pain but also the resilience of the Lebanese. Humor, constantly present in the background, is, after all, the politeness of despair.

As you leave the theater, Philippe’s voice and those of his parents linger, the echo of moving homes, the whirlwind of languages. Most of all, the taste of childhood remains: his mother’s fatayer, our Proustian Madeleine, inseparable from memory and comfort, lingering on the palate like the persistent sweetness of a city one can never truly leave.

Some emotions cannot be written; they must be experienced. It’s up to you to discover them.

Comments