On the occasion of World Heart Day, Ici Beyrouth invites you to dive into the advances in cardiac surgery and into a singular Lebanese history, from the first open-heart operations in Beirut to valve-preservation strategies. At the center of the story, the thread of a pioneer of Lebanese origin, Michael E. DeBakey, and a very concrete legacy for patients.

In the focused light of the operating room, a mini-incision; around the table, the Heart Team. In a few hours, a valve is repaired, an aorta reinforced, a myocardium sheltered. If the gesture seems more fluid and less traumatic today, it is because it relies on a century of innovations and transmission. Among its architects, Michael E. DeBakey, the son of Lebanese immigrants, redefined techniques and organization. His imprint still guides thousands of decisions and resonates in Beirut, where cardiac surgery has been built through pioneering achievements, schools and obstinacy.

Heart: What Has Really Changed

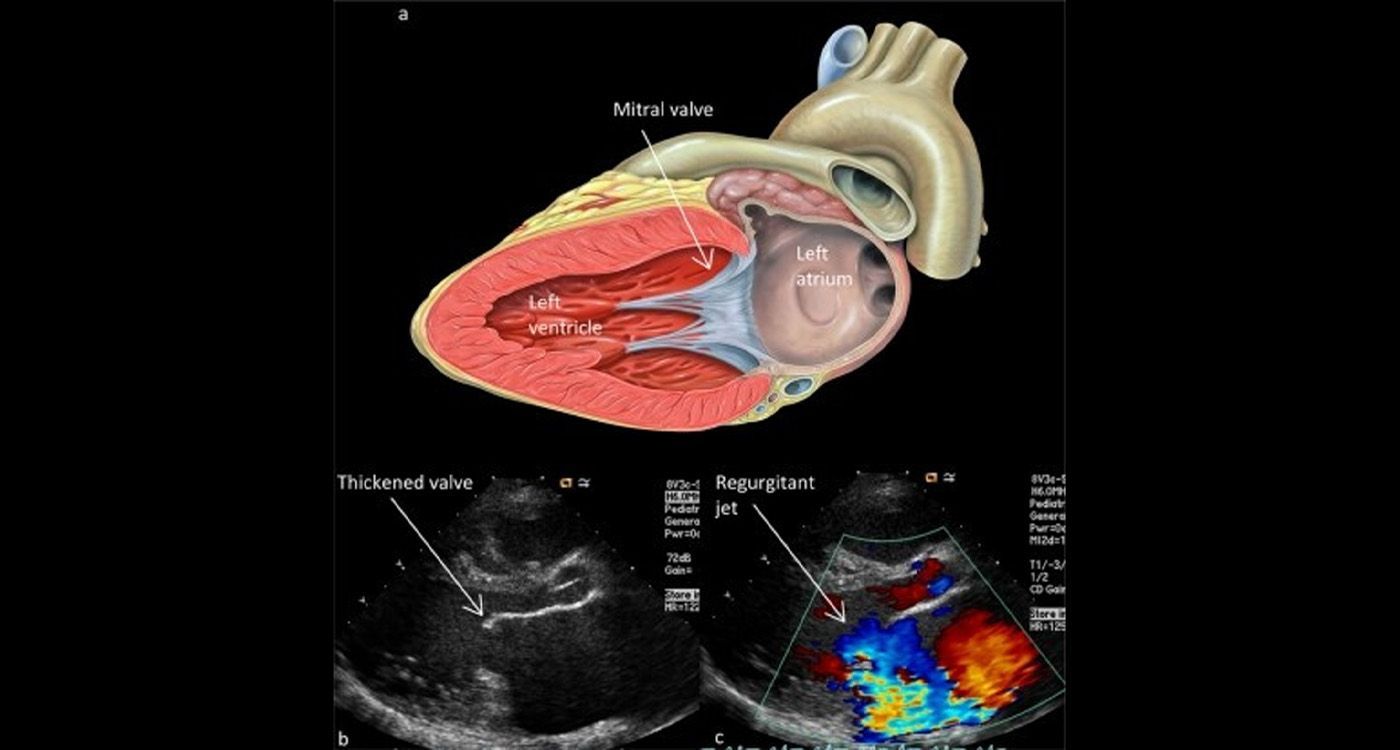

Reduced trauma, lighter approaches, better pain control. Coronary artery bypass remains a pillar (sometimes without cardiopulmonary bypass); valve surgery favors repair when possible, the aorta benefits from fine planning and hybrid techniques. The rise of structural heart (TAVI, percutaneous repairs) shifts boundaries: the Heart Team arbitrates case by case. The upshot: shorter stays, accelerated recovery and shared decision-making.

A Pioneer Called Michael E. DeBakey

Much more than the name of instruments or a classification of dissections (I–III), DeBakey contributed to the roller pump, popularized aortic grafts and imposed a culture of organization: protocols, evaluation, transmission — from the battlefield to civilian operating rooms. Born in the United States to Lebanese parents, he embodies a simple and demanding idea: a great procedure cannot exist without a great system. His lesson, less myth than method, has irrigated the world and inspires Lebanese teams.

At the Lebanese Front

April 1959, at AUBMC: first open-heart surgery in Lebanon, performed by Prof. Ibrahim Dagher on a cyanotic adult patient. According to AUBMC’s official history, Lebanon would then be the fourth country in the world to carry out this type of operation. The following year, a disk oxygenator designed locally made it possible to operate on a child: ingenuity in the service of excellence. Then came structured programs, cardiac intensive care and the spread of bypass surgery, valve surgery and aortic surgery. An identity took shape: learn fast, coordinate, accompany the patient all the way through rehabilitation.

The Imprint of Joe Hatem

In the 1980s–1990s, the reputation of Lebanese cardiac surgery became synonymous with a name, that of Joe Hatem, cardiac surgeon at Saint-George Hospital, then at LAU. Patients from across the Arab world came to be operated on by his reputed hands. He has often been described as the father of modern cardiac surgery in Lebanon. His distinctiveness also lies in his lucidity about the boundaries with interventional cardiology. He supervised, alongside the corresponding team, the country’s first angioplasty performed by Samir Alam at AUBMC in 1981. At the time: balloon-only angioplasty (without stent). Today, most angioplasties are performed with stent placement (often drug-eluting); the balloon alone is reserved for specific cases.

Later, he accompanied the emergence of percutaneous valves and reminded us of the value of covering everything that can be done without opening a chest when the patient’s benefit is greater. In 2012, Lebanon’s first TAVI was performed by Georges Ghanem at LAU, a milestone that opened a lasting program and an even closer collaboration between interventional cardiologists and surgeons.

Supports, Hybridizations, Pediatric Transplant

Lebanon has adopted ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: temporary circulatory and respiratory assistance) for cardiopulmonary distress and has drawn useful feedback from it. The pediatric pathway has been structured around the Children’s Heart Center (AUBMC) and the Brave Heart Fund (2003), which helps with financing. In 2017, the first successful pediatric heart transplant showed that a true chain of care exists, from the operation to rehabilitation.

Preserving the Valve, Repairing the Aorta

On September 25, 2024, Hôtel-Dieu de France performed a David-type procedure (team led by Ziad Khabbaz): the ascending aorta is replaced while keeping the aortic valve. Concrete benefit: avoiding a mechanical valve (lifelong anticoagulation) or a less durable bioprosthesis. This is the current trend: preserve when possible.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Lebanese Model

In short: we have everything in Lebanon — teams, technical platforms and Heart Teams. It is often costly; therefore, not easy for all social classes. The Ministry of Health, social security, insurance companies, mutual funds and NGOs (such as Brave Heart) are increasingly contributing.

A Legacy That Still Beats

The Lebanese story is continuity more than a showcase of “firsts”: from classic sternotomy to valve preservation, one and the same guiding line — choosing the most just solution for the patient, with method and transparency.

In the operating room, it is hands that save — and methods that guide those hands. From Dagher to Hatem, from today’s pathways to tomorrow’s firsts, Lebanon has proven that it knows how to learn and organize itself. On World Heart Day, the promise is simple and demanding: decide better, operate right, rehabilitate early, fund access — so that every heartbeat finds its chance, and so that the scar truly becomes a second life.

Comments