- Home

- Highlights

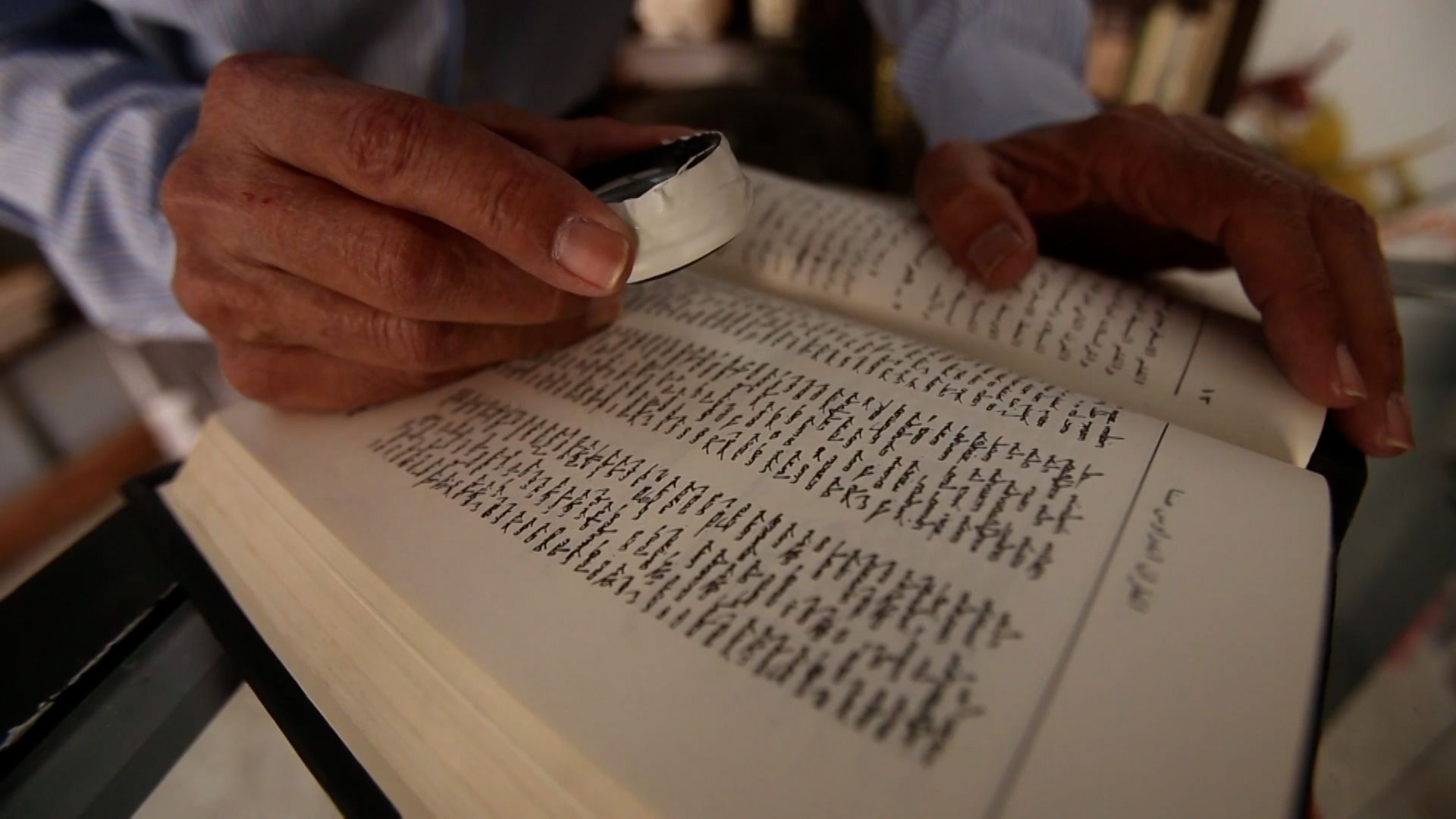

- Maaloula: The Last Sanctuary of the Language of Christ

©AFP

Nestled on the mountainside of Syria’s Qalamoun range, the village of Maaloula clings to time as it does to stone. Its sand-colored houses blend into the rock, its winding alleys read like pages from an ancient tale and women greet you with “Shlomo,” a traditional Aramaic salutation. In the dry air of this Christian enclave, a language the world has nearly forgotten still lingers: Aramaic, the language of Christ, according to tradition, once spoken by prophets and empires.

Here, just over 50 kilometers north of Damascus, Aramaic is still spoken, whispered, passed on between walls, in songs and in the rhythm of daily life. This linguistic miracle endures not through academic preservation, but through something far more fragile: a deep sense of belonging.

“It’s my mother’s language, and grandmother’s too,” says Mrya, 23. “We didn’t learn it at school. We learned it at the table, through bedtime stories. At home, we speak Aramaic.”

A Religious Legacy

Maaloula’s history is deeply rooted in Christianity. From the earliest centuries, the village became a major monastic center, home to sanctuaries and convents like the Monastery of Saint Thecla, named after a disciple of Paul of Tarsus and a key figure in Eastern Christianity. Carved into the rock, these sacred sites drew pilgrims long before the region embraced Islam. Aramaic survived not only in homes, but in liturgy, woven into prayers, chants and centuries of worship.

Today, Maaloula is a Christian enclave of Orthodox and Greek Catholic communities. It is a small island of linguistic heritage in the heart of predominantly Arabic-speaking, Muslim Syria. With just around 2,000 residents, far fewer than before the war, the village remains one of the last strongholds of Aramaic, once the lingua franca of the ancient Middle East.

Against All Odds

Aramaic is a Semitic language, closely related to Arabic and Hebrew, with roots stretching back nearly 3,000 years. For centuries, it served as the official language of powerful empires, used in royal inscriptions as well as commercial exchanges. According to Christian tradition, it is best known as the language spoken by Jesus Christ and his disciples.

However, over time, Aramaic has steadily faded, shaped by the historical and political shifts that have swept the Middle East. Starting in the 7th century, the gradual spread of Arabic displaced Aramaic in both cities and rural areas, where it now survives only in a few isolated communities.

According to UNESCO, the various Aramaic dialects are spoken today by only a few tens of thousands worldwide. Estimates vary by source, shaped by migration, conflict and the lack of recent studies. UNESCO classifies Aramaic as a “severely endangered” language, it is one of more than 40% of the world’s languages at risk of extinction. In that sense, Maaloula’s case is both unique and emblematic.

Elias, a history teacher in Damascus, notes that “the mountains saved the language.” The village is perched more than 1,500 meters above sea level. Its geographic isolation has allowed its residents to preserve a language the Syrian government has never officially recognized.

“The Aramaic spoken in Maaloula belongs to the Western Neo-Aramaic dialect family,” explains Father Rachid, an Aramaic scholar and professor. It differs from the Aramaic spoken by Assyrian communities in northern Iraq and Syria, as well as from the variants used by Chaldean communities in Iran. Each small community has its own version, complete with distinct accents and expressions. In addition to Maaloula, two other Syrian villages, Jubb’adin and Bakhaa, preserve closely related forms of Western Aramaic, Father Rachid notes.

Beyond these isolated linguistic pockets, Aramaic is finding new life within diaspora communities. In countries like Sweden, Germany, the United States and Australia, Assyrian and Chaldean churches are working to keep the language alive, especially among younger generations born abroad.

Tshakla’s family immigrated to Canada after the war began. “My parents still speak Aramaic with each other,” she says. “They use it when they talk on the phone with friends from Syria, or when they go to church here. They’re deeply afraid of losing this language they’re so proud of.”

A Language of Identity and Memory

In Maaloula, Aramaic is more than a means of communication, it is a fragile line of defense against cultural erasure. In a Syria fractured by identity struggles, where Arabic serves as both a national symbol and a political instrument, speaking Aramaic becomes a way of embracing otherness, a deliberate dissonance, almost an act of quiet resistance.

“When we pray, we still speak the words of Christ,” says Rena, 42, a devoted believer. “It’s a sacred language, a bond between us and our ancestors. It carries our faith, our history. Aramaic is more than just our language, it’s a way of looking at the world.”

When a language is lost, so is a way of understanding the world. As French linguist Louis-Jean Calvet explains, every language is a symbolic system, a means of naming and structuring the world. It creates an inseparable link between language, identity and territory.

Yet, this bond is paradoxically fragile. Younger generations use Arabic daily, at school, in the streets, on social media. Aramaic is mostly confined to private spaces, religious ceremonies and family conversations. And when they leave Maaloula for Damascus or Beirut, the language almost entirely fades away. Mrya sums up this dual reality, “With my friends, we speak Arabic. But at home, Aramaic comes back, when we want to tell a story or express something we can’t say any other way.”

“It’s not a language that helps you find work,” admits Rena, “but it’s my greatest source of pride.”

Maaloula: The Last Refuge

This small village embodies both the hopes and dangers tied to the survival of the Aramaic language. In 2013, it was overtaken by jihadist groups who committed atrocities, destroyed sacred sites and forced part of the population to flee. Although the Syrian army reclaimed Maaloula, the scars remain visible.

“Many have left and won’t be coming back,” says Mireille, a local shopkeeper. “Language and culture are tied to the land. Lose the village, and you lose everything.”

Maaloula, the last stronghold of an ancient language, reflects both the beauty and fragility of a global linguistic heritage. This Syrian enclave serves as a reminder that minority languages are far more than mere curiosities, they embody entire worlds, histories and identities delicately balanced between past and future.

“I don’t know how much longer Aramaic will be spoken, and that scares me,” says Mrya. “But I will teach my language to my children and grandchildren, hoping others will do the same.”

This is not just an isolated case, it reflects many similar situations worldwide. Everywhere, the same struggle unfolds between passing language down within families and the pressure to conform to a single linguistic standard.

* All first names have been changed to protect anonymity.

Read more

Comments