Born from a crushing failure and a fleeting vision on a beach in Normandy, A Man and a Woman lifted Claude Lelouch from oblivion to cinematic legend. This is the improbable origin of a film that became a myth of French cinema.

At first, there was nothing but the bitter silence of a man convinced his career was over. In 1965, Claude Lelouch was a young director in free fall. At 27, he had just endured one of the most humiliating flops of his early career: Les Grands Moments – booed at Cannes, ignored in theaters, savaged by critics. “They said I was only good for filming weddings,” he would later recall. He considered giving it all up.

So he left. With no plan, no script and almost no money. He packed his car, tossed a 16 mm camera in the back, and drove toward Normandy – toward Deauville. The sea, the emptiness – he expected nothing. And yet it was there, on that misty, windswept beach, that inspiration struck.

He couldn’t explain why the scene moved him so deeply: a woman walking in the distance, with a young boy and a dog. An ordinary moment that hit him. “I saw the whole film in that instant, all at once,” he later said. He didn’t yet know who they were or what their story would be – only the essence: two people, each bearing the weight of loss, drawn together by something fragile and ineffable. A man, a woman. Nothing more.

Back in Paris, Lelouch clung to that image. Instead of writing a conventional script, he sketched a loose treatment – a narrative outline he entrusted almost entirely to his actors. He wanted authenticity, unspoken emotion, raw feeling. It would be up to the actors to embody the story. He cast Anouk Aimée, whose quiet beauty and emotional restraint made her a natural Anne. For the widowed race car driver, he chose Jean-Louis Trintignant, whose calm presence and introspective energy gave the character depth.

With minimal resources, modest funding and a small crew, Lelouch shot using handheld cameras, natural light and partially improvised scenes. He even used music he hadn’t yet secured the rights for – just as placeholders. But each frame radiates sincerity. The camera moves gently between the characters, catching their silences, their hesitations, their smallest gestures.

The alternation between color and black and white wasn’t a stylistic flourish – it became a language. Color for the present; black and white for memory, doubt and absence. In truth, it was also a necessity. Color film was expensive, so Lelouch used it when he could, and black-and-white when he had no choice. Constraint became style. Limitations became a signature.

There was still one thing missing: the music. Lelouch turned to a young, unknown composer – Francis Lai – and asked for a simple, recurring theme, like a heartbeat. What emerged was the now-iconic “Chabadabada,” a wordless refrain hummed across generations. A melody that echoed the film’s silences, its restrained longing, its quiet grace.

The music became the film’s soul. It punctuated the story’s rhythms, mirrored its emotional shifts, and held its delicate narrative together. Lelouch wasn’t telling a love story in the usual sense. He was capturing something more elusive: the mourning of a love that might have been.

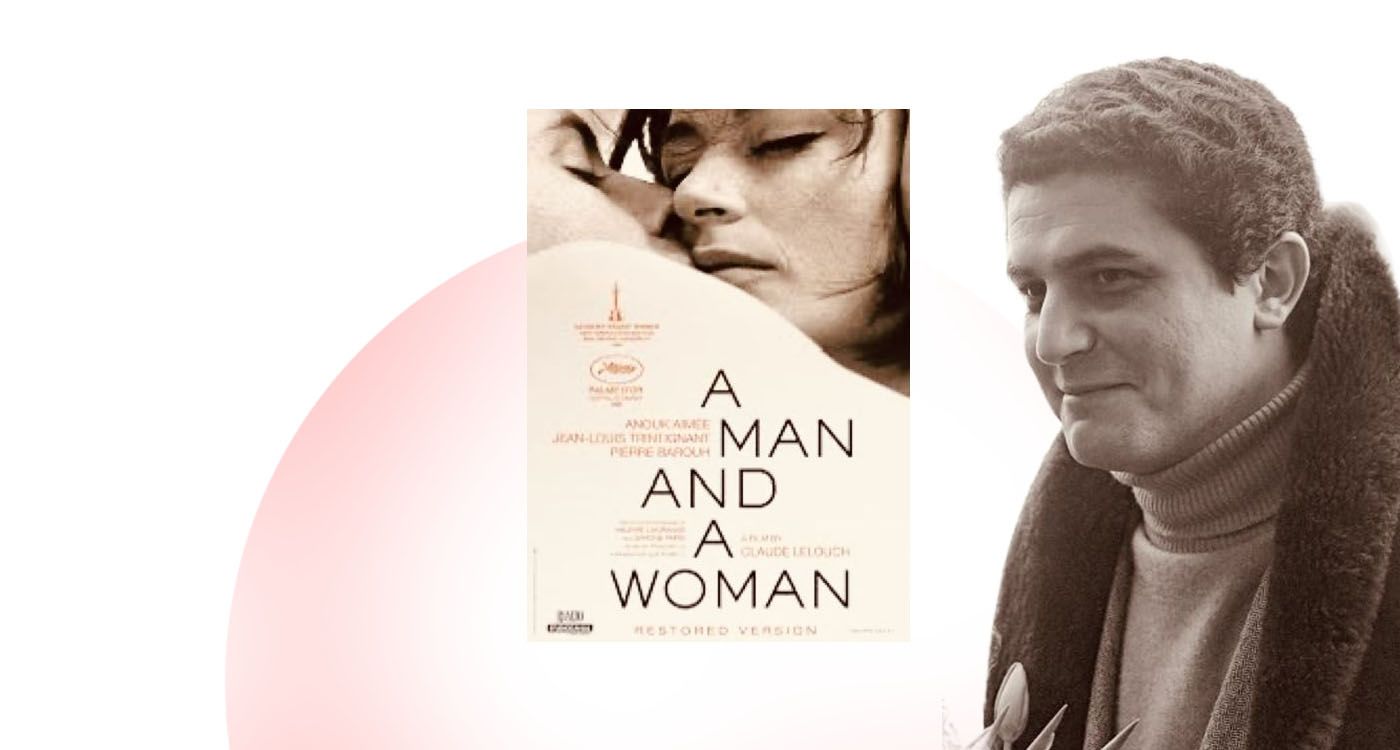

The official poster of the 78th edition of the Cannes Film Festival in 2025 is proof that this film remains timeless. Graphic design © Hartland Villa

When A Man and a Woman premiered in 1966, no one saw it coming – not Lelouch, not the producers, not the distributors. And yet, the improbable happened. The film was received not merely as a success, but as a revelation. At Cannes, it won the Palme d’Or. In Hollywood, it earned two Academy Awards – for Best Foreign Language Film and Best Original Screenplay – as well as a Golden Globe. In just a few months, Lelouch went from a failed filmmaker to an international sensation.

Audiences around the world were deeply moved. The film became a cult classic, its style widely imitated, its music echoing across continents. A Man and a Woman ushered in a cinema of restraint and emotional nuance, a romanticism for adults – far removed from clichés. This was a story where desire simmered quietly beneath the surface, where love was possible but never guaranteed. A love story suspended in uncertainty. That doubt – that fragility – is precisely what made the film feel so modern.

With this single film, Lelouch established a signature style: fluid, handheld camerawork; realistic, often improvised dialogue; editing guided by rhythm and music; and an ever-present sense of memory. It was a cinema of intimacy and movement, of spontaneity and emotion. He wasn’t chasing technical polish – he was filming the pulse of a feeling, the beat of a heart.

But the impact of A Man and a Woman reached far beyond its immediate success. It inspired a generation of filmmakers and gave Lelouch the freedom to follow his own path – outside institutions, beyond convention, unfettered by trends. What continues to fascinate is not only the film itself, but the improbable way it came to life. From nothing – from a moment of absolute doubt – Lelouch created a masterpiece. Not through a meticulously crafted script or a grand career strategy, but through a fleeting emotion: the silhouette of a woman in the mist.

A Man and a Woman is lasting proof that a film can be born from a single image, from a moment suspended in time – and that utter failure can sometimes be the quiet prologue to global triumph. Lelouch, who believed he was saying goodbye to cinema, had in fact just redefined one of its most poetic languages.

Anecdotes, Legends and Sequels of a Masterpiece

A Shoestring Shoot

Claude Lelouch shot A Man and a Woman with no permits at many locations, especially in Deauville. Some beach scenes were filmed at dawn, on the sly, using minimal equipment. Oftentimes, he captured moments in a single take, believing spontaneity was more valuable than technical polish.

The Dialogues? Loosely Drawn

Very few lines were written in advance. Lelouch gave Anouk Aimée and Jean-Louis Trintignant only the beginnings of sentences, letting them improvise the rest. He wasn’t after rehearsed delivery – he wanted the immediacy of real emotion, the truth of the moment.

The Last-Minute ‘Chabadabada’

The film’s iconic “Chabadabada” theme was never part of the original plan. Lelouch had hoped to use a Brazilian bossa nova track, but couldn’t secure the rights. Composer Francis Lai stepped in to write an original melody. Pierre Barouh – who also played a role in the film – improvised placeholder vocals with nonsensical syllables. Lelouch loved the raw, emotional simplicity of it. What was meant to be a demo became the final, unforgettable version.

The Film’s Sequels

A Man and a Woman: 20 Years Later (1986)

Twenty years on, Lelouch brought Aimée and Trintignant back for a meditative sequel. Jean-Louis and Anne reunite – older, marked by time, memory and what might have been. The film, though less impactful than the original, resonates as a quiet, nostalgic epilogue.

The Best Years of a Life (2019)

In 2019, Lelouch completed the trilogy with a final chapter steeped in reflection. Trintignant, now frail and battling illness, plays an aging Jean-Louis in a retirement home. The film is a poetic farewell – a meditation on memory, aging and love that endures despite time’s toll.

Lelouch’s Guiding Instinct

This ethos runs through the entirety of Lelouch’s work. A Man and a Woman is perhaps its purest expression – born from spontaneity, lived-in imperfection, and the quiet power of sincere

Nearly sixty years later, the image of Anouk Aimée walking along the Deauville beach still lingers – an indelible silhouette in the memory of cinema.

Comments