Every year on May 30, the world marks World Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Day. But in Lebanon, this year’s message is urgent: while treatments for MS have advanced, the struggling healthcare system of the Cedar's country is putting patients at serious risk.

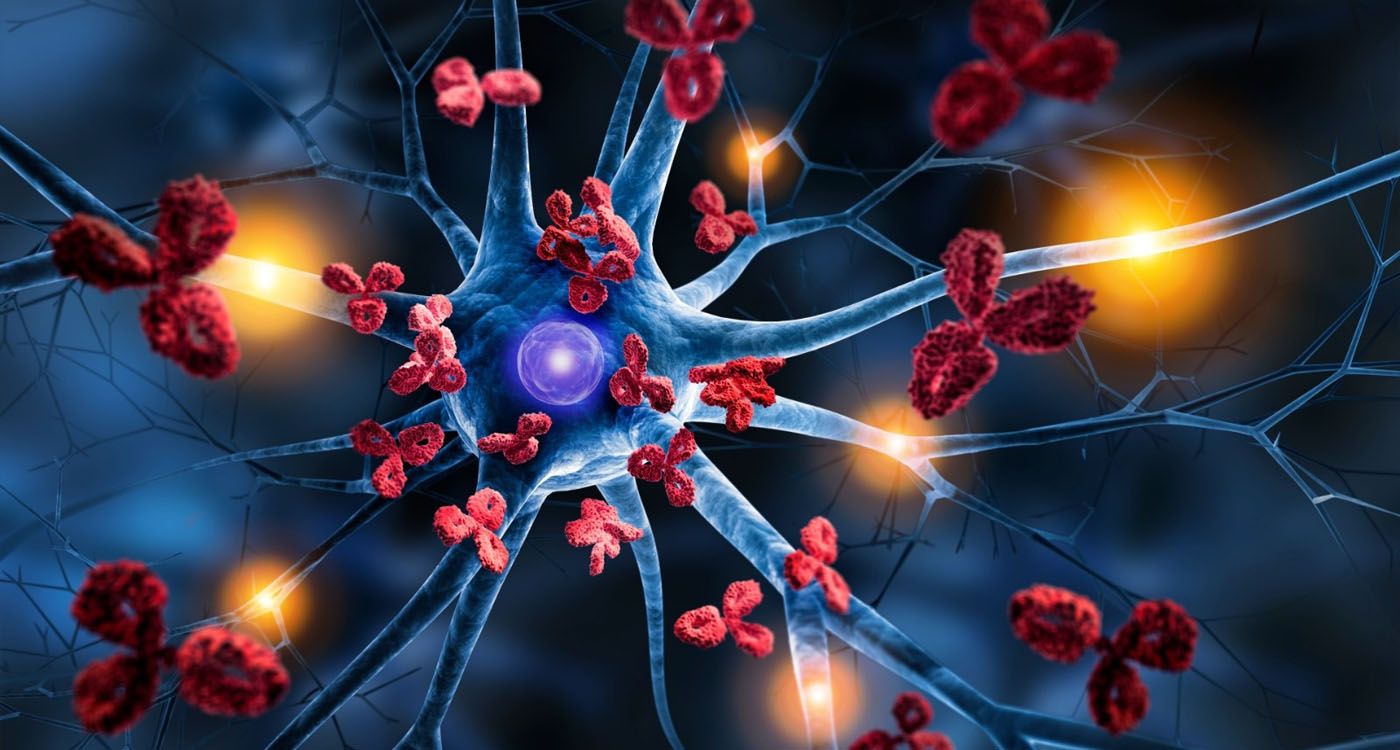

MS is a chronic disease that affects the brain and spinal cord. It happens when the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the protective layer around nerves, causing communication problems between the brain and the rest of the body. This leads to symptoms like trouble walking, vision problems, numbness, bladder issues, fatigue, and sometimes depression.

MS usually starts in young adults and is more prevalent among women, especially between the ages of 20 and 40. There are two main types: a relapsing-remitting form, with flare-ups followed by periods of recovery (this is the most common type), and a progressive form, which slowly worsens over time.

A Growing Prevalence in Lebanon

The most recent study on MS in Lebanon was conducted in 2018 by Dr. Maya Zeineddine, a certified MS specialist and Clinical Associate Professor at the School of Pharmacy of the Lebanese American University (LAU). This study identified around 2,500 confirmed cases of multiple sclerosis across the country. “Today, we estimate that the number has risen to over 3,000,” Dr. Zeineddine explains to This is Beirut, “as the prevalence of MS continues to increase across the region.” This estimate is supported by the latest Atlas of MS published by the Multiple Sclerosis International Federation in 2023.

What explains this rise? Dr. Zeineddine points to several factors: earlier diagnosis thanks to updated criteria, the use of more advanced imaging technology—particularly 3-Tesla MRI machines, which are much more accurate than those used a decade ago—and growing awareness about MS among both the public and healthcare professionals. In addition, people with MS are living longer due to better treatments. “Several subspecialties now contribute to confirming diagnoses,” she adds, “such as neuroradiologists and neuro-ophthalmologists.”

As a result, Lebanon is now considered a moderately high-prevalence country for MS, with about 63 cases per 100,000 people. For comparison, France—which is classified as a high-prevalence country—has around 120 cases per 100,000.

From Regional Leader to Collapse

Just a few years ago, Lebanon stood out as a regional pioneer in the treatment of MS. At one point, the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) covered 100% of MS treatment costs, and patients had access to all available drug classes without any limitations,” recalls Dr. Zeineddine. “Even the National Social Security Fund (NSSF) reimbursed up to 90% of the treatment expenses.” In addition to that, institutions like the COOP, the Lebanese Army, the Internal Security Forces (ISF), and various private insurance companies all contributed as third-party payers. This broad and comprehensive coverage made Lebanon a model country in the region for MS care.

However, this progress came to a halt with the onset of the economic crisis in 2019. “Today, the Ministry of Public Health provides only two treatments—interferon beta-1a and off-label rituximab,” Dr. Zeineddine explains, “while more than 18 MS therapies are approved and available worldwide.” As a result of the crisis, several major pharmaceutical companies have withdrawn from the Lebanese market, leaving patients with very limited options and worsening their condition.

The impact of the economic collapse has been devastating. In a recent study conducted by Dr. Zeineddine, 62% of MS patients reported that they had stopped their treatment. “This is a catastrophic figure,” she warns, “because the neurological damage caused by MS cannot be reversed, leaving affected patients with permanent disability. Without proper treatment, a patient's quality of life declines very quickly.”

The NSSF, which once led the way in providing financial support for MS patients, now covers barely 10% of actual treatment costs. As a result, most patients are left to manage their disease on their own. Only a few private insurance companies still offer full or partial coverage for newer and more effective MS therapies.

A Lifelong Treatment, at an Exorbitant Cost

Multiple sclerosis is not like cancer—it isn’t treated for a limited period, but requires lifelong management. The high cost of MS medications makes them difficult to access for many patients. In addition, the limited treatment options available in Lebanon are not suitable for everyone. For instance, patients with a fear of needles are not good candidates for interferon injections, while those who suffer from recurrent infections or cannot regularly visit hospitals or infusion centers may not be eligible for rituximab.

Beyond the cost of medications, patients must also bear the expenses of regular follow-up visits, annual MRIs, routine blood tests to monitor medication safety, and consultations with various specialists such as ophthalmologists, psychiatrists, urologists, physiotherapists, etc. MS can also lead to complications like infections, depression, and urinary problems, which require additional care. Non-drug treatments, such as physiotherapy and psychotherapy, are often essential, as is the use of assistive devices like canes or wheelchairs. Yet, none of these services or tools are typically covered by public or private insurance, placing a heavy financial burden on patients and their families.

An Underfunded Fight

“Unlike the strong public support and fundraising we often see for cancer patients, MS is underfunded and overlooked,” says Dr. Maya Zeineddine. “Yet it is a serious, disabling and complex disease that affects thousands of young people.” She warns that Lebanon is at serious risk of losing the progress it once made in building a solid foundation for MS care.

People with MS may walk normally today and begin to limp tomorrow. As for the future—they hold on to hope. But hope alone cannot replace medication, MRI scans, or the political commitment needed to rebuild a collapsing system. In Lebanon, it’s not the patients’ legs that are failing them—it’s the healthcare system that is breaking down.

Comments