Lebanon, weakened by war and economic crisis, is once again seeing a push to establish mega-centers for voting. Promoted as a practical and fair solution for displaced voters, the idea still faces strong political resistance. A closer look at the stakes, past attempts and what it would truly take to overhaul the country’s voting system.

Tens of thousands of displaced voters, devastated towns and an approaching election deadline. As South Lebanon continues to bear the heavy toll of the war with Israel, a pressing question looms: How can citizens, forced to flee their homes, still exercise their right to vote? For many observers and reform advocates, mega-centers offer a pragmatic solution to this challenge.

What Is a Mega-Voting Center?

A mega-voting center is a high-capacity polling station, typically located in urban areas, that allows voters to cast their ballots from their place of residence, eliminating the need to travel to their registered constituency.

Unlike Lebanon’s traditional system, which mandates that voters cast their ballots in their area of registration—often their hometown—mega-centers provide a centralized alternative. This solution aims to simplify voting access and boost electoral participation.

Why Are Mega-Centers Sparking Debate in Lebanon?

The question holds particular importance in the current Lebanese context. Since the escalation of the conflict between Hezbollah and Israel in the fall of 2024, many towns in South Lebanon have been devastated. Tens of thousands of people have been forced to flee to Beirut and other major cities.

In this context, how can these displaced voters be allowed to exercise their right to vote without having to return to areas that are now destroyed or inaccessible?

A growing number of political parties, NGOs and political figures argue that mega-centers are not only a practical response to this dilemma, but also a stepping stone toward modernizing Lebanon's electoral system. They believe that mega-centers could reduce transportation costs for voters and limit the political pressures, threats and patronage that often define voting in traditional strongholds.

The idea faces fierce resistance, particularly from the Hezbollah-Amal duo. These parties view the reform as a threat to their political dominance in southern municipalities.

The Amal movement, led by Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri, rejects the idea of allowing displaced voters to cast their ballots in a mega-center located in Beirut or elsewhere in the country. Instead, the Shiite movement prefers that displaced voters vote in neighboring towns close to their devastated villages, which would remain under the duo's influence, ensuring political control over the election.

For Amal and Hezbollah, the establishment of mega-centers could disrupt the electoral balance within the Shiite community. These parties accuse their opponents of promoting this reform to weaken their representation, while discontent simmers within their own ranks, fueled by years of socio-economic crises and the 2024 war.

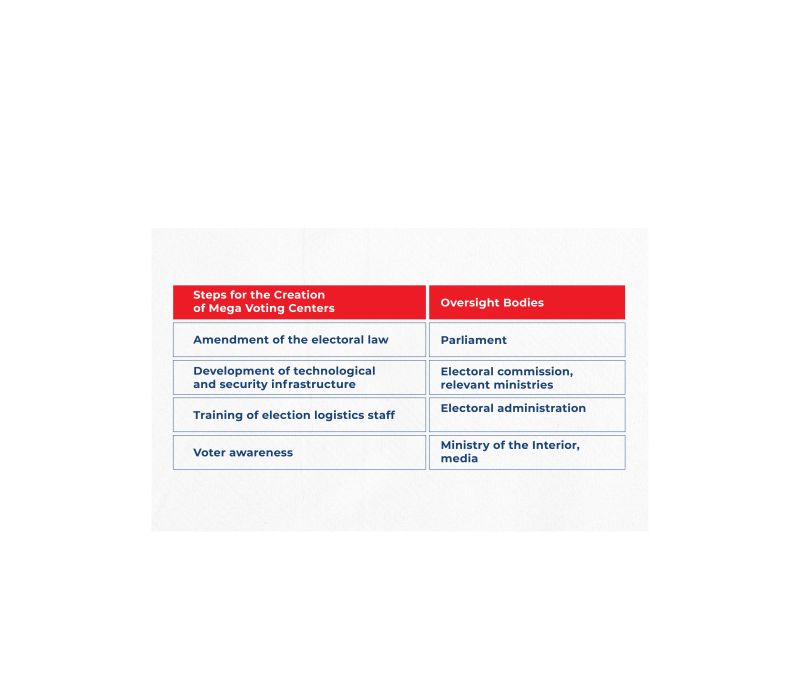

Required Steps for Implementation

The establishment of a mega-voting center brings about a significant shift in the electoral process. It typically requires legal, administrative and logistical reforms, as it alters both how voters access the polls and how elections are organized.

Legally, such a move would necessitate an amendment to the current electoral law. Allowing voters to cast ballots outside their registered constituency challenges core principles such as the link between voter registration and local representation, the structure of electoral lists by region and safeguards against double voting.

Once the legal framework is established, the administrative process takes over. The first step is identifying mega-centers that are accessible, spacious, well-equipped and secure. A reliable voter identification system must also be implemented, one capable of accurately authenticating registrants from various regions. Electoral staff should be trained to efficiently manage the high volume of voters from different localities.

Finally, the vote counting process must be adapted to this centralized system—often with the support of automated or semi-automated tools—to ensure swift and transparent results.

A Well-Tested Model

The concept of a mega-voting center, often seen as an ambitious reform, is not exactly new. It has already been successfully implemented in several countries.

A clear example is illustrated by the Lebanese diaspora. During the 2018 and 2022 legislative elections, the Lebanese Embassy and consulates in France established multiple mega-voting centers in large public venues, such as gyms, cultural centers and municipal halls, spread across the entire French territory.

Approximately 28,000 Lebanese nationals residing in France registered to vote in 2022, three times the number from 2018. Germany registered 17,000 voters, while the entire African continent registered 20,000.

Voters were grouped by geographical areas to streamline logistics and improve participation. The voting process followed traditional procedures, with securely collected ballots sent back to Lebanon for counting.

Lebanese expatriates’ right to vote was granted through an amendment to the electoral law in 2017.

Other countries have adopted similar systems. In South Africa, for instance, voters can cast their ballots at any polling station nationwide, provided they notify authorities in advance. In the United States, Texas allows voters to vote at any polling station within the county, regardless of their registered address, thanks to interconnected electoral databases.

An Unsuccessful Attempt in 2022

In 2022, Lebanon considered for the first time the idea of setting up mega-voting centers for the legislative elections. An interministerial committee, tasked with assessing their feasibility, quickly highlighted the project’s limitations.

According to a report from the Ministry of Interior, implementing the reform would have required at least five months after amending the electoral law and a budget of approximately $5.9 million. Faced with these legal, logistical and financial challenges, the Council of Ministers postponed the project and referred it back to a commission for further study—a discussion that has yet to yield tangible results.

As Lebanon heads toward the 2025 municipal and local elections, the debate over mega-voting centers highlights broader tensions: between political control and electoral fairness, between tradition and reform, and between the urgent needs of a displaced population and the inertia of a fractured political system.

Comments