As the sun begins to rise at the start of spring, a sense of calm seems to have settled into the daily lives of the Lebanese, following a ceasefire reached a few months ago between Israel and Hezbollah (despite occasional breaches of the truce in southern Lebanon and the Beqaa). We sought to understand how the Lebanese are faring.

Behind the repeated phrases heard from those interviewed on the streets of Beirut, such as “Kater Kheir Allah (Praise be to God), I’m breathing, I’m alive,” and “Thank God, I haven’t lost a loved one in the war,” lie much deeper and more complex emotions.

Measured Hope and Optimism

A closer look reveals that hope and optimism still hold a fragile place in the lives of Hussein, Nabil and Bilal.

Hussein is in high spirits this March morning. The man in his 40s, who works in security, proudly shows me the denim jacket and pants he bought “at a low-cost store” for his two daughters, aged four and nine.

“Of course, I have hope; without it, I’d die,” he assures me. Yet, behind this single father’s smile lies a man with deeper concerns. “If the opportunity arose, I wouldn’t hesitate to change my life and move to a country where people are respected,” he confides.

For 60-year-old banker Nabil, who splits his time between Monaco and Beirut, “the tide has turned for the better.”

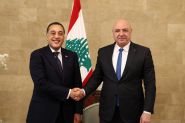

“We were in a very bad place. Now, I’m optimistic. There are people who genuinely want to move the country forward,” he stresses, referring to President Joseph Aoun and Prime Minister Salam’s government. However, Nabil tempers his optimism, saying these changes must “become tangible” in the economic sector.

Bilal, who is 50 years old, also expresses a positive outlook on recent political and security developments in Lebanon. Yet, like Nabil, his hope remains “measured” as “only promises are being made” for now, he adds.

According to psychoanalyst Reina M. Sarkis, the positive news mentioned above—including the fall of the Baath Party, the collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s regime and the diminishing power of Hezbollah—“are most welcome” after six years of violent upheaval that have taken a heavy toll on the Lebanese psyche.

“We reached such depths of despair and degradation that, at one point, it seemed almost impossible to envision optimistic scenarios. Now, however, things have changed,” she says.

While Sarkis senses a growing desire for optimism, she clarifies that “it’s not euphoria, far from it.”

This feeling must be taken “with caution and much apprehension,” as many people “are still confronted by a harsh reality and no longer dare to believe,” especially those over 40 who “have seen it all”—having lived through the immense disillusionment following the 2005 Cedar Revolution, the 2019 “Thawra” and the 2020 Beirut port double explosion.

Without My Children’s Help, I’d Be Begging

Jessica, the owner of a mini-market, acknowledges that without the support of her two sons, who work in Africa, she wouldn’t be able to support herself. “Thanks to my children, I was able to treat my dental and skin issues and even buy a car,” she shares before adding, “As long as the cost of living remains this high, I have no real hope for any meaningful change in the country.”

Psychoanalyst Sarkis explains that the Lebanese have experienced “a severe fall” following the 2019 economic crisis, from which “they have yet to recover—both financially and psychologically.” She adds, “One of the main pillars of their lives has been undermined, including their sense of security, as the small savings they had—whether modest or substantial—have disappeared,” she adds.

According to Sarkis, the financial factor is “a central issue that lingers in the background. It’s the common thread connecting the major upheavals of wars and violence, including the most recent conflict (the war between Israel and Hezbollah), which affected everyone, even if the bombs didn’t directly target all of them.”

‘I Don’t Know Where My Life Is Heading’

Carla, a 55-year-old waitress, feels that “nothing is going right.” With a sorrowful expression, she confides, “I no longer feel joy; I don’t know where my life is going anymore! My days end at 11:30 PM after 10 hours of work for a modest salary of $500, which barely covers my rent, health insurance and the neighborhood generator.” Additionally, she is housing her daughter and granddaughter, whose home was destroyed in the war.

This loss of direction in life is something psychoanalyst Sarkis observes in some of her patients. “They are unhappy, unsure of where to turn and don’t know what life has in store for them.” “It takes immense courage to keep hoping,” she asserts.

‘Deep Changes Take Time’

Bilal, speaking realistically, acknowledges that profound changes, whether psychological or national, “take time.” The Lebanese people have endured too many setbacks in their country’s recent history.

This perspective is shared by Sarkis, who observes that “everything unfolds in nuance, in paradoxes and especially over long periods, particularly when it comes to a nation’s history.”

For her, the Lebanese are “in a period of respite, during which everyone is trying to heal their wounds.”

However, she adds, “The traumas remain, and they won’t disappear unless we take the time to address and work through them. It’s a process that happens not only on an individual level in therapy, but should ideally involve a broader movement. It needs to spill over from private spaces into the social and political spheres, ultimately becoming a national effort—a collective will to rebuild both the land and the minds. Unfortunately, I don’t think we’re there yet,” concludes Sarkis.

Comments