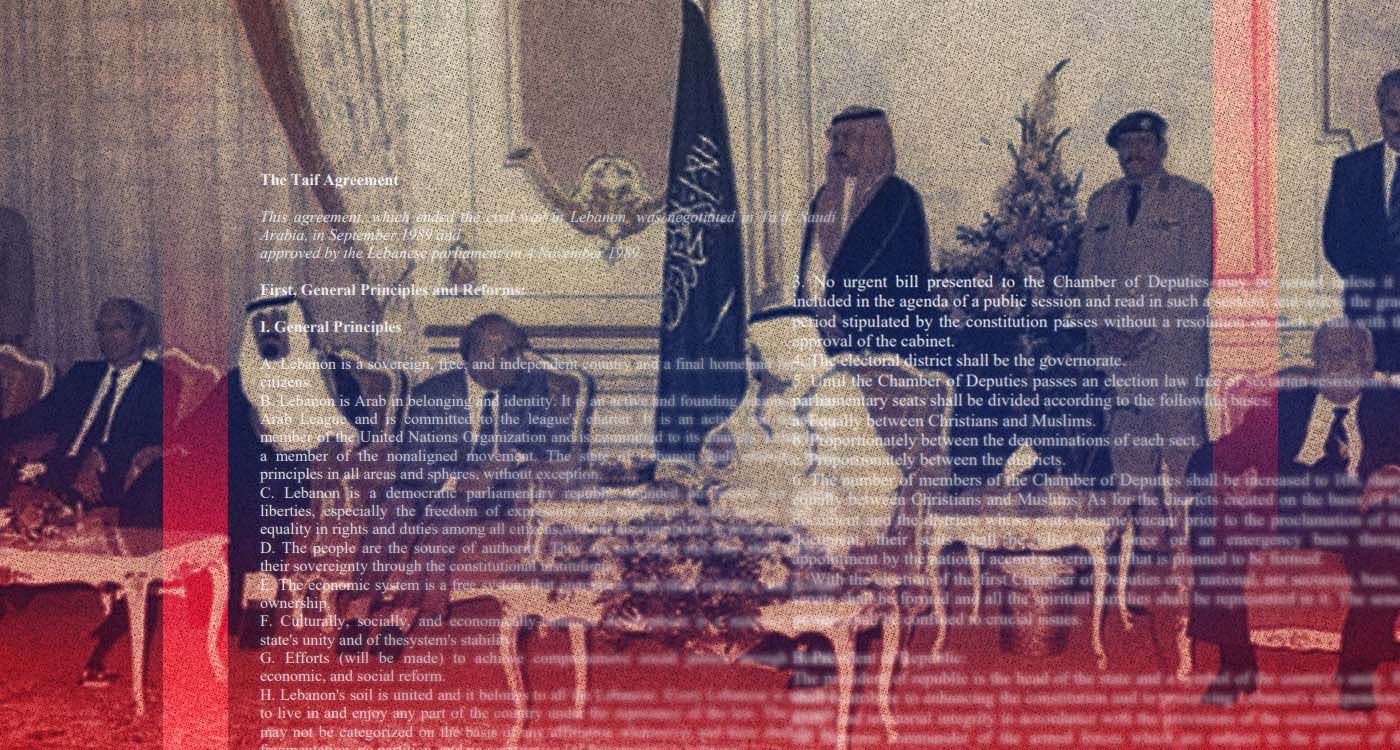

Prime Minister Nawaf Salam is determined to implement the Taif Agreement. His commitment to this accord is not new as Taif marked a clear transition between war and peace in Lebanon and provided various political factions with guarantees in governance.

Salam has consistently expressed his support for Taif—not just after being appointed Prime Minister and forming his government, but even long before. Those familiar with his writings and statements recognize Taif's central role in his political philosophy and discourse.

However, and unfortunately, its implementation has not begun with the fundamental reforms it envisions, but rather with symbolic formalities, such as the location of Cabinet meetings. The agreement stipulates that Cabinet sessions be held in a neutral location, and a site near the National Museum was chosen for this purpose. The objective at the time was to prevent any sectarian group from appearing to control or dominate the government. This practice continued for years before meetings returned to Baabda Palace and the Grand Serail during President Michel Sleiman’s tenure. Yet, the public barely noticed the change—an indication of how minor this issue is compared to Lebanon’s deeper crises.

Suppose there is a genuine will to implement Taif. In that case, the focus should be on the core political and constitutional provisions that remain unfulfilled—provisions crucial to pulling Lebanon out of decades of political deadlock.

Major reforms outlined in Taif, such as establishing a Senate to safeguard sectarian rights or abolishing political sectarianism, remain unrealistic given Lebanon’s current turmoil. But at the very least, the constitutional and political provisions of the agreement must be enforced as Lebanon has endured prolonged presidential vacuums with no legal safeguards in place. The agreement's ambiguity has left key questions unanswered: How long can a prime minister-designate take to form a government? What constitutes the legal quorum for electing a president? How can ministerial portfolios be distributed without cementing sectarian entitlements?

Taif never clarified why parliamentary seats were increased from 108 to 128, nor did it define the criteria for public sector appointments across administrative ranks.

It failed to establish a transparent mechanism for appointments, the distribution of powers in government formation, decision-making, voting procedures, or even how Parliament should function effectively.

If Taif is to be implemented in good faith, these critical issues must be addressed first. The ambiguity surrounding the agreement must be resolved, and it must be enacted in full—without manipulation or selective interpretation—to give it a true chance of success. Engaging in debates over the location of Cabinet meetings is a distraction from Lebanon’s real challenges. After all, a venue does not change the essence of governance.

Comments