Loss can reveal a narcissistic fragility, where to lose is to lose oneself. Navigating identity collapse, self-idealization, and myths of vengeance, this article delves into the psychic suffering caused by loss through the perspectives of psychoanalysis and literature.

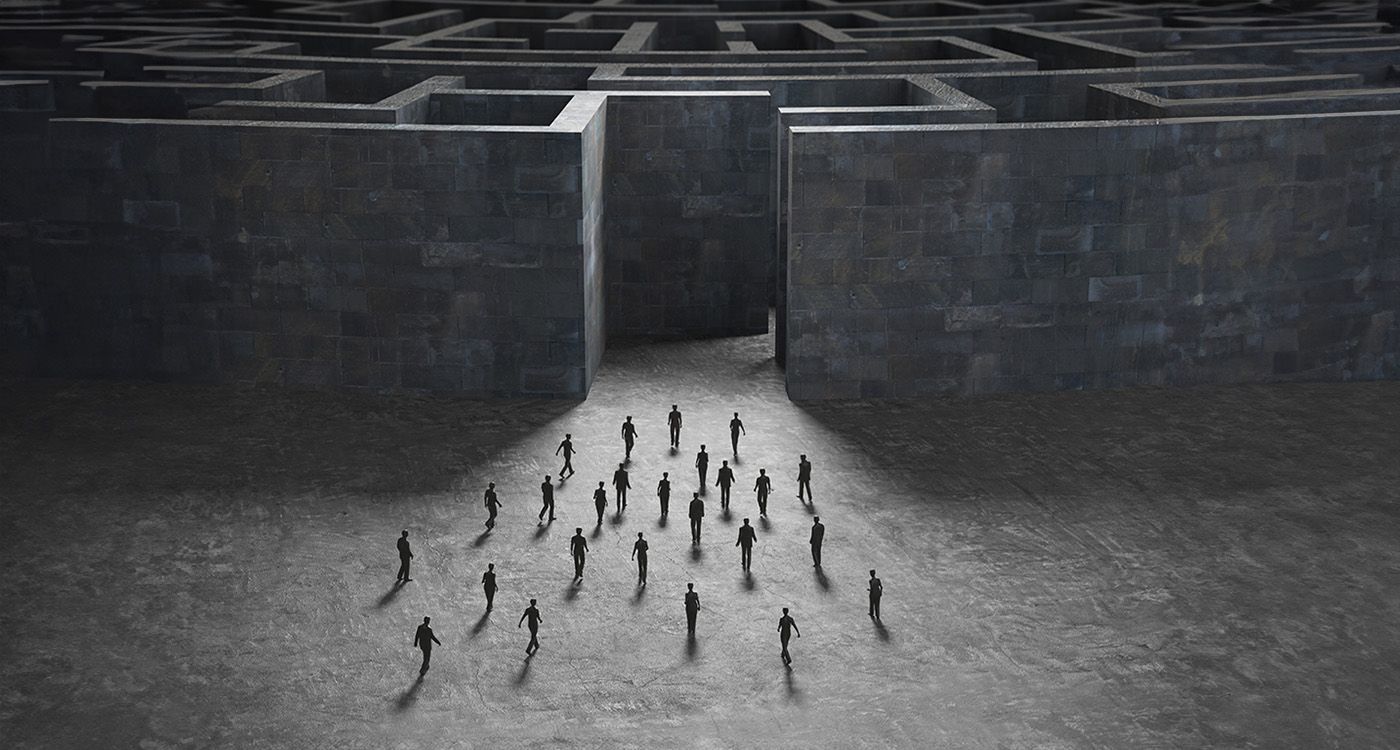

Loss, in its psychic dimension, can reveal a fundamental fragility within our being. Whether personal or collective, it does more than disrupt our balance—it can jeopardize our very sense of identity. In these critical moments, to lose becomes synonymous with losing oneself, exposing a profound narcissistic vulnerability.

In fact, excessive narcissism is often tied to an intense need for recognition and admiration, making individuals particularly intolerant of defeat. Freud described how narcissistic suffering can result from the confrontation with reality, where the individual pursuit of a grandiose self-image finds itself facing losses that undermine this identity construct. This narcissistic disappointment generates pain not only from what has been lost but also from what was never realized, leading to feelings of failure and despair—a form of psychic death. The individual may feel that this loss is not simply external, but an attack on their very essence. This perception is frequently exacerbated by past experiences of rejection or abandonment, which deepen the self-devaluing beliefs. It is not uncommon, in such cases, for the defense mechanism of denial to be set in motion.

Explanation: The ideal self represents an individual's aspirations and desires for accomplishment, often shaped by parental expectations and societal norms. In contrast, the superego embodies moral values and prohibitions, primarily rooted in the rules essential for communal living. In healthy psychological development, these two components should function in a complementary manner, allowing the individual to aspire to ideals while integrating ethical boundaries. However, when the ideal self and superego merge, they can create a rigid psychic structure, where the subject feels a persecutory pressure to meet unattainable standards. This coalescence fosters an intolerance of failure and criticism, amplifying feelings of shame and devaluation. As psychoanalyst Otto Kernberg notes, this dynamic can lead to significant ego inflation, where the individual perceives himself as superior, yet remains deeply vulnerable to narcissistic wounds. While this mechanism may serve as a form of protection, it also creates its own fragility: the individual becomes dependent on this idealized self-image, fearing any potential failure and denying it in order to transform it into a victory. Far from being a barrier against suffering, this entrenched structure becomes a source of vulnerability, exposing the individual to major psychological instability.

The origins of the difficulty in tolerating loss often trace back to childhood, a period marked by early experiences of frustration. Some parents, driven by narcissistic love, create an environment where their child develops without constraints, with his desires immediately satisfied. This so-called “positive” education, which is anything but positive, limits the child’s ability to confront the unavoidable hardships of existence. Deprived of the essential lesson in limits, the child fails to develop the ability to see himself as just one subject among many, confronted with obstacles and inevitable failures. The resulting adult becomes particularly vulnerable, torn between feelings of omnipotence and a paralyzing fear of failure.

Other children develop under the pressure of excessive parental ideals, becoming the bearers of their parents' unfulfilled ambitions. Their identity is forged through disproportionate expectations, where each success is eclipsed by new demands for perfection. Trapped in a cycle of perfectionism and self-imposed demands, these children become adults tormented by chronic dissatisfaction, unable to recognize their worth apart from parental gaze. Their relationship to loss becomes particularly painful, with each failure lived as a fundamental negation of their being.

On another level, the rupture of a significant bond—be it affective, ideal, or symbolic—can trigger a significant narcissistic collapse. This occurs, for instance, in the loss of someone close. In Deuil et mélancolie (Mourning and Melancholia), Freud makes an essential distinction between normal mourning and melancholia. While mourning allows for a gradual detachment from the lost object, melancholia leads the subject to an unconscious identification dynamic, causing them to internalize the loss and sink into persistent self-devaluation.

The melancholic individual finds himself trapped in a deadlock, compelled to integrate his suffering as a component of his being, unable to externalize it. Rather than progressing toward accepting the separation, his pain becomes a constant and draining rumination. This pathological fixation on the lost object keeps him stuck in a cycle of self-punishment and continuous devaluation. Unable to release himself from what is no longer, he feels his psychic energy gradually depleting, leading either to immobilism or to relentless self-depreciation. Deprived of his psychic energy, he gradually loses the ability to maintain a stable and acceptable sense of himself.

On a collective level, the loss of a fundamental reference point—be it political, religious, or ideological—can also trigger an identity crisis that weakens the cohesion of a group. History thus becomes a stage for compulsive repetition, where past traumas transform into myths of revenge and symbolic reconstruction.

This is what happens in certain ideologies built around a myth of retribution for millennial defeats, fostering in followers a deep thirst for vengeance, anchored in an all-powerful and divine collective force. This process, which structures the group’s identity, strengthens identifications by reframing the defeat within an eschatological perspective, where the triumphant return becomes a necessary horizon. The idealization of suffering and the anticipation of future victory, become a closed psychic framework that blocks any process of change. The persistence of these patterns in cultural transmission sustains a collective imagination driven by identity retreat and the rejection of a different “other.”

This type of construction reduces the capacity to process loss, freezing history within a perpetual cycle of confrontation while rejecting any form of otherness. Historical events are symbolically appropriated to mold collective identity, forging a selective memory that transcends mere transmission, evolving into a political and psychological tool. This process entraps groups in patterns of victimization, obstructing reconciliation and hindering the resolution of trauma.

Literature, as an expression of human experience, mirrors these psychic mechanisms in different ways, revealing the complexity of the relationship between the individual and loss. Psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva, in Soleil Noir (Black Sun), explores melancholia not only as a psychic state but also as a creative process, where writing allows one to contain and metabolize the feeling of absence. What speech cannot directly articulate, writing shapes, offering a path through the pain of mourning. Shakespeare, in turn, illustrates the destructive effects of lost ideals in his characters Macbeth and Othello: in Macbeth, a deep sense of guilt intertwined with self-loathing drives the character to the extremes of moral boundaries, generating a vertigo of violence and dehumanization. In Othello, consumed by a destructive jealousy, the character collapses under the crushing weight of paranoid obsession. In both plays, loss is not just a trauma; it becomes a powerful, often lethal driving force—a place of metamorphosis where the frameworks of identity and connection to the world are redefined.

The major challenge, both personal and collective, lies in transforming loss into an opportunity for psychological and societal reconstruction. Letting go of illusions of omnipotence becomes the foundation of a psychological equilibrium capable of withstanding life’s hardships without collapse, embracing uncertainty and loss as natural life components rather than existential threats.

Comments