Beyrouth Forever, David Hury’s crime novel, explores with rare intensity the buried memories of Lebanon. Blending criminal investigation and historical reflection, this dark and necessary novel questions the flaws of a society plagued by corruption, denial of the past, and the concealment of truth.

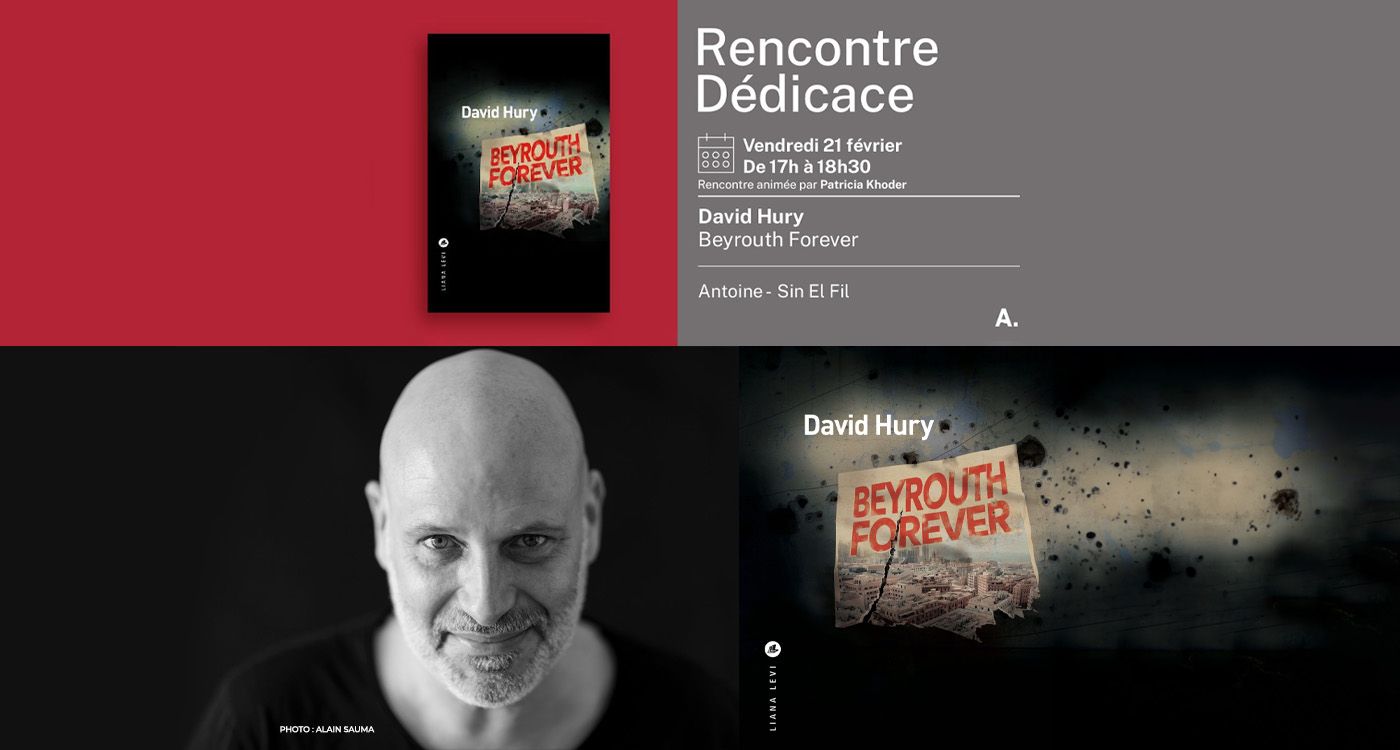

Published in January 2025 by Liana Levi, Beyrouth Forever marks an evolution in David Hury’s literary journey. Before this, he had already explored other genres, with historical novels like Mustapha s’en va-t-en guerre (2021) and Sans nouvelles depuis Drancy (2024), as well as Pentes douces (2017), an illustrated novel. In an interview with This is Beirut, the author reflects on his transition from journalism to fiction. After the Paris launch, a discussion and book signing will take place in Beirut on February 21 at 5 PM at Librairie Antoine (Sin el-Fil).

Through the story of a disillusioned inspector confronted with an investigation with complex political and historical ramifications, Beyrouth Forever paints a portrait of a Lebanon consumed by corruption, manipulated memory, and structural impotence. Is it a noir novel? A political thriller? A social chronicle? This text is all of these at once. Underlying it all, a haunting question runs through its pages: what remains of truth in a country where the past has never been fully confronted?

A Crime Novel at the Heart of a Corrupt System

The novel opens in an oppressive Beirut, suffocated by heat and inertia. Marwan Khalil, a homicide detective and former Christian militiaman who has never been able to move on from the 1975 civil war, drags his weary body and cynicism through the decrepit corridors of a police station where bureaucracy outweighs justice. From the very first lines, the tone is set: “The building is austere, the atmosphere toxic. The sun has only been up for three hours, but the air is already humid and salty.” The city itself seems to participate in the moral suffocation of its characters.

Marwan’s investigation begins with the discovery of the body of Aimée Asmar, an elderly woman found dead in her apartment. Initially treated as a natural death, the case quickly takes a more complex turn when it is revealed that Aimée was working on a controversial manuscript—an attempt to write a unified history of Lebanon from 1943 to 2020. A project that might seem trivial elsewhere becomes a threat here. In a country where each community holds its own version of history, seeking to establish a common narrative is already taking sides.

As Marwan progresses in his investigation, he faces pressure from “above.” His superiors order him to close the case quickly, a clear sign that Aimée’s death is disturbing certain powers. “Those above had left him no choice. He just hoped this damn case would be the last of his career.”

Marwan knows he is trapped in a system where truth is just an adjustable variable. His disillusionment echoes that of an entire people, resigned to seeing investigations buried before they even begin.

The Manipulation of the Past

The central element of the novel is this unfinished manuscript. By attempting to reconstruct a shared historical narrative, Aimée Asmar touched on a national taboo: Lebanon’s history is fragmented into multiple parallel narratives, each serving the interests of its own community. Marwan quickly realizes that the disappearance of the manuscript and Aimée’s death are no coincidence. This unified school textbook, continuously postponed by the ruling factions—starting with Hezbollah—disturbs those who benefit from the status quo and sectarian divisions.

On this sensitive topic, which remains highly relevant in Lebanon, David Hury shared with This is Beirut: “The Lebanese school textbook has been on my mind for a long time. In the early 2000s, I was teaching in the Francophone journalism master’s program at the Lebanese University. I was always surprised by my students’ total lack of knowledge about Lebanese history, and more generally, Middle Eastern history. How can you build a society if each person learns only one version of history? So yes, it’s a burning issue, a real contemporary topic…”

Hury illustrates one of the country’s most tragic paradoxes: although the civil war (1975-1990) is present in collective memory, it remains an unresolved national enigma. As one of Marwan’s colleagues puts it:

“Here, history is like a corpse—you hide it under a rug and pretend it doesn’t exist.”

The Disillusionment of a Man Facing His Country

The character of Marwan Khalil embodies this inner struggle between acceptance and revolt. A former Christian militia fighter during the war, he became a policeman more out of necessity than vocation. His illusions have long since shattered, yet part of him refuses to sink entirely into cynicism. His relationship with his daughter Maha, who has left to live in France, symbolizes both his personal failure and that of an entire generation.

Hury excels in painting a schizophrenic Beirut, where the splendor of renovated facades barely conceals the misery eating away at its foundations. Through Marwan’s wanderings, the novel unfolds a biting critique of a political class that thrives on the country’s ruins. The dialogues are sharp, often tinged with bitter irony. “You’ll see, in twenty years, they’ll still be selling us elections as a victory for democracy.”

Marwan knows everything is a charade, yet he continues—perhaps out of habit, perhaps out of a faint glimmer of hope.

Marwan forms an investigative duo with his young partner, Ibtissam Abou Zeid, an idealistic Shiite breaking away from her community. On this narrative choice, David Hury explains: “Writing a novel is first and foremost about creating characters that readers can relate to or detest. It’s a very classic technique to pair opposites: age, gender, social background, motivations… This allowed me to depict two sides of Lebanon, but also the internal fracture of the main character, whose daughter left Beirut after the August 2020 port explosion.”

For the author, this opposing duo represents more than just a literary device: “Their contrast is obvious, but I see it more as a complementarity. The generational divide has long been one of Lebanon’s most fascinating aspects…”

From Journalism to Fiction

After 18 years covering Lebanon as a journalist, David Hury wanted to move from observation to storytelling. This transition happened naturally, nourished by years of encounters and personal archives.

“I was a journalist in Beirut for many years, and there was always something frustrating about it: the impossibility of recounting what happens on the margins, off the record, the things that can’t be written in articles. Over the years, I recorded my loved ones, and then people less close to me. I accumulated hours of recordings telling history through individual perspectives. Of course, they talked about the 1975-1990 war, but not only that. It’s been ten years since I left Beirut, and I’ve had time to digest all these stories—including my own. It was easy for me to draw from this material to create fiction. Beyrouth Forever contains a lot of lived experience: major themes, but also small everyday details. For example, when Marwan climbs onto his rooftop to check his water tank and finds only ten centimeters of water, where larvae wriggle… How many times did that happen to me?”

When asked about real-life inspirations for his characters, particularly Aimée Asmar, the murdered historian, David Hury remains vague: “For character development, I blended real and fictional elements. This applies to Aimée Asmar as much as the others…”

Blending crime fiction, social critique, and reflections on collective memory, Beyrouth Forever is a novel of rare intensity. Far from offering answers, it raises an essential question: how can you build the future when the past remains a powder keg?

A dark, relentless, but absolutely necessary novel.

Comments