In 1842, in his Paris apartment, Frédéric Chopin signed his Ballade in F minor, Op. 52. One of the two incomplete autographs of this work, which survived among others likely lost, was recently acquired by the Fryderyk Chopin Institute. This 79-measure manuscript offers a fascinating glimpse into the composer’s creative process, marked by revisions and meticulous adjustments.

It was a calm winter morning in Paris in 1842. The biting wind blew through the cobblestone streets, spreading the season's cold. In the musician's apartment, a soft warmth emanated from the hearth: the flames danced and crackled, brilliant and lively. Leaning over his Pleyel piano, a man brought music to life. His fingers caressed the ivory keys with a natural ease, almost innate, conjuring chords, melodies, and harmonies that blossomed like ideas in the making, breaking the silence. This man was Fryderyk (or Frédéric, as he was called in France) Chopin, a composer of the Romantic era whose masterpieces would transcend borders and time. That day, he was absorbed in writing what would become one of his most famous pieces: the Ballade in F minor, Op. 52. Yet, even for the genius he was, composition did not come without creative struggle. His fingers glided over the piano with the same finesse as his pen on the manuscript, tirelessly seeking the right phrase, the ultimate feeling.

Preliminary Sketch

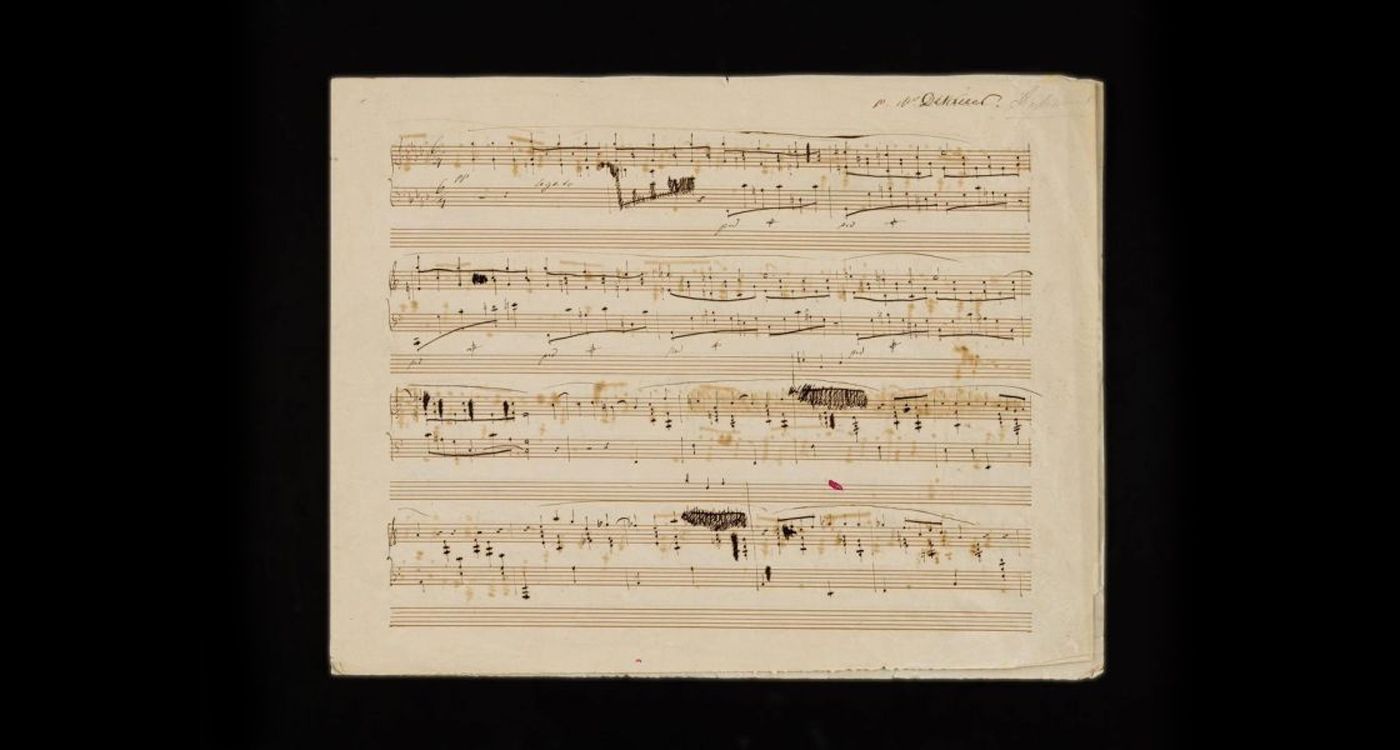

Several months had passed, and this Fourth Ballade was gradually taking shape. The musical ideas of the “poet of Poland” were molding and redefining, sometimes hesitant, often bold. It was during these moments of hard work that various autographs of the Ballade in F minor came to be. Of these, only two incomplete manuscripts have survived through the ages: one kept at the Bodleian Library in Oxford and another, a fragment in the original 6/4 meter, part of the private collection of the heirs of Rudolf F. Kallir (1895-1987) in New York, which was acquired by the Fryderyk Chopin Institute at the end of 2024. This latter manuscript, containing the first 79 measures of the work, constitutes a preliminary sketch, a glimpse into Chopin’s creative process, rich in corrections and additions. This score would travel a long way before finding a place of honor in Warsaw, Poland.

Indeed, after the death of the Polish genius on October 17, 1849, in Paris, his sister Ludwika Jędrzejewiczowa handed the autograph of the Ballade to Chopin’s friend, pianist and composer Joseph Dessauer (1798-1876), as indicated by an inscription she made in the upper-right corner of the first page: “p[our] M[.] Desauer” (To M. Dessauer). In 1933, this autograph was acquired in an antique shop in Lucerne by Rudolf F. Kallir, a collector of artworks, musical autographs, and correspondence from famous composers, writers, and scientists. In 1940, Kallir left Europe and settled permanently in New York. Until now, the autograph of the Ballade Op. 52 had only been known through black-and-white photographs taken in the 1950s. The collector was aware that he was holding an invaluable document in his hands; he kept it carefully, never making it public, keeping it hidden from even researchers.

Working Material

The inadequate quality of the available photographs prevented detailed analysis and in-depth study of this precious source. The autograph takes the form of a bifolio containing measures 1 to 79 of the composition. It was initially meant to serve as the basis for the first French edition (Maurice Schlesinger, Paris, 1843). Although ultimately rejected by Chopin, the composer used it as working material on which he continued to refine the details of the composition. Analyzing the elements contained in this manuscript will provide valuable insight into Chopin’s thinking during his creative process.

It was only in 2024, after lengthy and discreet negotiations, that the Fryderyk Chopin Institute in Warsaw succeeded in acquiring this manuscript, with the financial support of the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. From June 12 until the end of October 2025, it will be exhibited at the Fryderyk Chopin Museum (Muzeum Fryderyka Chopina) as part of the temporary exhibition titled La Vie romantique. Chopin, Scheffer, Delacroix, and Sand, which will complement the 19th Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition in Warsaw. Thus, this manuscript will finally return to the homeland that Chopin held with deep religious fervor. Exiled throughout his life from his oppressed Poland, he remained, despite his adoption by France, a Pole in soul, heart, and destiny.

Digital Endurance

Furthermore, aware of the digital challenges our era faces, the Fryderyk Chopin Institute embarked on another major project: the deposit of digital copies of Chopin’s original manuscripts in the Arctic World Archive, located on Spitsbergen Island in the Svalbard archipelago, Norway. Recorded on celluloid film, these copies benefit from long-term preservation, ensuring their protection for nearly 500 years. Thanks to methods independent of computer hardware and the internet, they are resistant to cyber threats. Recognized for its security and autonomy, the Arctic World Archive remains one of the safest places to store such data. This initiative aims to preserve Chopin’s musical legacy, ensuring its faithful transmission to future generations, regardless of the vagaries of time. The devastating fire in Los Angeles, which reduced Arnold Schoenberg’s (1874-1951) house to ashes, along with more than 100,000 manuscripts and objects belonging to the composer, poignantly illustrates the necessity of such an initiative.

Comments