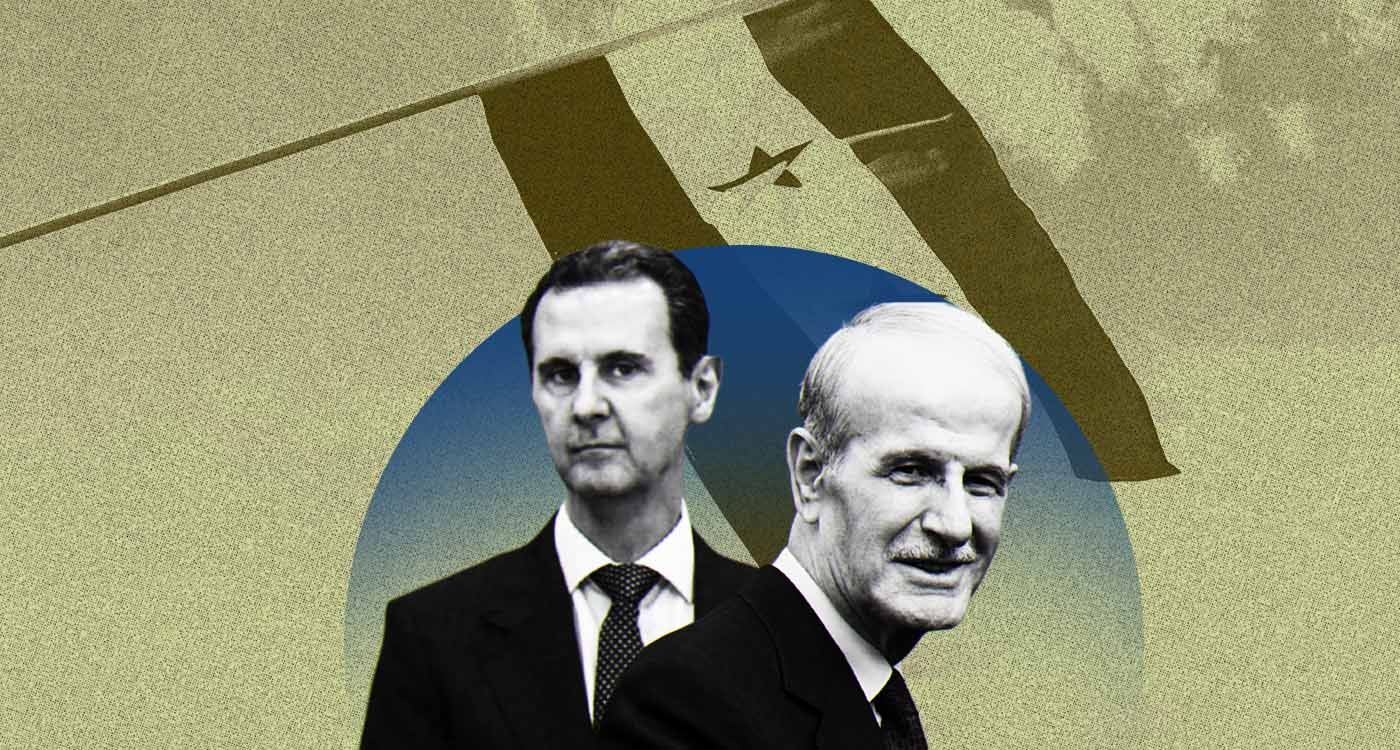

Four years ago, Lebanon celebrated the centennial of Greater Lebanon’s creation. It is important to acknowledge that almost half of these one hundred years were marked by the unfortunate conflicts with the Assad regime, from the early 1970s to the dramatic downfall of Bashar al-Assad and his regime on December 8, a historic day.

Lebanon’s complex relationship with Syria is not a recent phenomenon and dates back to the early 20th century. However, the political, and more notably, the military and security policies of the Assad family over the past 50 years reflect the severe challenges that the Lebanese people endured during this dark chapter of their modern history. That said, the early 1970s had the potential to mark the beginning of a new era of balanced cooperation between the two countries.

Hafez al-Assad emerged as Syria’s strongman in November 1970 following a coup within the Baath Party. By February 1971, he had assumed the presidency, and in March of that year, he was confirmed through a referendum in line with the Baath Party's tradition, garnering over 90% of the vote. These events hold particular significance for Lebanon as they coincided with Sleiman Frangieh's (grandfather of current Marada leader) election as President in 1970. The well-established ties between the Frangieh and Assad families, forged at the end of the 1950s, were widely recognized. With both leaders assuming power simultaneously, there were high expectations for the development of a trustful and balanced relationship between the two countries. However, this expectation did not materialize, and this historical opportunity was squandered due to the hegemonic policies of Syria’s new regime. From the very beginning, Hafez al-Assad outlined a strategy that extended beyond Lebanon: to establish Syria as a key regional power by asserting dominance over neighboring countries and regional actors. To achieve this goal, the Syrian regime’s approach was consistent: fostering internal divisions among its neighbors while maintaining a state of perpetual destabilization that would prevent the emergence of a unified, powerful central authority.

President Frangieh Recalled to Order

The first signs of this strategy appeared as early as 1973, when Hafez al-Assad closed Syria’s borders with Lebanon in an attempt to pressure President Frangieh into halting the Lebanese army's operation aimed at curbing the armed Palestinian factions present in the country. The persistent violations by Palestinian guerrillas, particularly after the 1969 Cairo Agreement, created a tense and hostile atmosphere that significantly weakened the authority and sovereignty of the Lebanese state.

President Frangieh’s attempts to put an end to Palestinian transgressions were intended to restore the credibility of the central government and establish a semblance of stability. However, this approach conflicted with Hafez al-Assad’s ambitions, prompting him to distance himself from Frangieh and actively undermine the state’s efforts to stabilize Lebanon.

The outbreak of the war in Lebanon in April 1975 gave Hafez al-Assad a prime opportunity to bolster his strategy of chronic destabilization by fueling the conflict and leveraging existing divisions. Assad successfully reached an unofficial agreement with Israel to transform Lebanon into a battleground for proxy wars, thus avoiding a direct confrontation between Syria and Israel—a strategy that would later be adopted by Iran in the early 2000s.

To achieve this, Assad aimed to prevent the rise of any powerful, stabilizing force. In the early stages of the war, in 1976, when the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), led by Yasser Arafat, and the National Movement, a leftist-Islamist coalition led by Kamal Joumblatt, launched a significant offensive against the Christian-controlled eastern regions, the Syrian regime intervened militarily. The dual objective was to halt the Palestinian-leftist offensive and establish a military presence in Lebanon to solidify its influence.

Assad’s policy involved preventing any one faction from gaining dominance over the other, which meant curbing the emergence of any leader with significant power. This policy is evident in the assassination of Kamal Joumblatt, the leader of the National Movement, on March 16, 1977, on a road in the Chouf region near a Syrian checkpoint. To weaken the Christian (sovereigntist) factions further, the Syrian army conducted extensive bombing raids on their strongholds in 1978 and again in 1981, targeting areas such as Zahleh.

Halt Sarkis' Autonomy in Decision-Making

Simultaneously, Hafez al-Assad would undermine all attempts at internal unity or stabilization, both locally and internationally. Arab and foreign mediations were systematically nipped in the bud, as was the case with French, Algerian or Vatican-led efforts. For the Syrian regime, any conciliation effort had to go through Damascus. When President Elias Sarkis, after his election in 1976, took the initiative to tour Arab countries in search of substantial aid, Hafez al-Assad disapproved of this decision-making autonomy on Sarkis' part and had the airport bombed as a “reminder of the order” (yet another one!) just as the head of state was about to leave.

Meanwhile, Damascus adopted a systematic approach to expel the Arab countries that had initially sent military contingents to establish the Arab Deterrent Force (ADF), intended to restore order, security and stability in Lebanon. Seeing this mission as a threat to his strategy, Assad's regime sought to retain sole control over the ADF, pressuring the other Arab nations to gradually withdraw their troops, one after the other.

However, these hostile actions were not enough. They had to be coupled with the elimination of any significant leader who refused to bow to Damascus' demands, or those striving to promote internal unity or work towards the restoration of a sovereign state authority. The Syrian regime thus engaged in a series of political assassinations, particularly targeting President Bashir Gemayel (on September 14, 1982), the Mufti of the Republic Hassan Khaled (on May 16, 1989), newly elected President René Moawad (on November 22, 1989) and, of course, Prime Minister Rafic Hariri (on February 14, 2005), as well as the leaders and key figures of the Cedar Revolution in 2005.

Humiliations and Violations of Dignity

To complete this “Anschluss-like” operation, Damascus also sought to humiliate the country’s political establishment on a daily basis. It was through the media that lawmakers learned of Hafez al-Assad’s decision to extend President Elias Hrawi’s mandate. Rafic Hariri was subjected to direct threats and had to endure Bashar al-Assad’s insulting behavior when summoned to Damascus to be informed of the decision to extend President Emile Lahoud’s term. Hariri complied with the Syrian dictate on this matter, but that did not prevent his assassination, nor did it halt the series of political murders that followed.

After Bashar al-Assad assumed office in 2000, succeeding his father, the young president showed some cautious signs of openness, particularly toward the Christian camp. Former minister Fouad Boutros was tasked with initiating a dialogue with Syria’s new leader. However, after three rounds of talks that initially seemed promising, Boutros noticed a clear shift in tone and attitude from Bashar al-Assad. It appeared that the regime’s old guards had expressed their dissatisfaction.

This brief attempt at openness lasted only a fleeting moment. Soon after, Bashar al-Assad revived his father’s strategy, fully embracing internal discord and perpetual destabilization. But it proved in vain... On this December 8, a date that will undoubtedly mark the history of the Middle East, few Lebanese mourn the end of the Assad era. The true challenge now lies in forging a better future for both the Lebanese and Syrian peoples.

Comments