Every week, we invite you to explore a striking theme to reveal its depth and richness. These lapidary, often provocative formulas open up new perspectives on the intricacies of the human psyche. By deciphering these quotes with rigor and pedagogy, we invite you on a fascinating journey to the heart of psychoanalytic thought to better understand our desires, anxieties and relationships with others. Ready to dive into the deep waters of the unconscious?

“A war is never against a country. A war is always a battle of egos and ideologies between a handful of people who use the country as their tool.”

This relevant and timely quote comes from the French-Ivorian footballer Stéphane Owona. It will help us examine the unconscious motivations that drive leaders to engage their nations in devastating conflicts.

At the heart of these motivations lies the pathological narcissism of these leaders. We know that narcissism is, in fact, a normal stage of human development. However, when this primary narcissism persists into adulthood, it can result in destructive behaviors. Narcissistic leaders tend to overestimate their abilities, perceive themselves as indispensable, constantly seek admiration from others and fundamentally lack empathy, even if they outwardly display the opposite. These personality traits can lead them to project their inflated egos onto the national and international stage, using their country as an extension of their own idealized self-image. Any opposition is seen as a personal threat to be eliminated. Their primary goal is to fulfill their need for control and glory, in a constant quest for recognition.

These pathological traits can drive such leaders to use war as a means of satisfying an ever-hungry and unsatisfied ego, ensuring their domination at the expense of the real interests of their country and people. Their patriotic slogans deceive infantilized citizens, who blindly sacrifice their most cherished possessions and even take pride in doing so. War thus becomes a tool to feed the sense of grandeur of those who consider themselves providential saviors, as well as to satisfy their megalomaniacal ambition to leave a historical mark, with no regard for the devastating consequences on people’s lives and property.

Ideological and dogmatic blindness is another crucial aspect of the psychological dynamic of these wartime leaders. A rigid attachment to an ideology can be understood as a defense mechanism, as described by Freud in Civilization and Its Discontents. This delusion manifests itself through the rejection of any contradictory information, the demonization of opponents and the justification of morally reprehensible actions in the name of their cause. Through the phenomenon of identification with the aggressor, some project their unresolved transgenerational traumatic wounds onto others by means of denial and splitting, which leads them to reject any contradictory reality. By desperately clinging to their ideology, they create a sense of certainty and security that shields them from existential anxiety and the questioning of their beliefs.

Attachment to the benefits of power is another powerful psychological driver in the development of conflicts. Freud’s concept of the death drive sheds light on this pathological attachment of leaders to their material and psychological advantages. Engaging in war, it is the death drive that invades their ego, not only allowing the abolition of the prohibition against murder but also prompting a morbid enjoyment in the destruction, suffering and death of others, reduced to mere waste.

The desire for domination manifests as an insatiable quest for wealth and privileges, a will to resist any change, regardless of the well-being of human lives. This dynamic reflects what Freud describes in his response to Einstein’s “Why War?” where he evokes the destructive impulses inherent in human nature. Leaders, by clinging to power and its privileges, permit themselves to unleash their destructive drives, all while justifying them through ideological or nationalistic motives.

In particularly pernicious cases, some leaders may regress to more primitive positions during times of great psychological tension, projecting their own fears and aggressions onto other nations to justify the conflict. Jacques Lacan, through his theory of the mirror stage, might interpret the need for recognition and affirmation of their image as leaders as an infantile motivation behind wars initiated by egocentric leaders. The underlying fragility of their ego drives them to develop and maintain an image of a grandiose self. They become masters at manipulating the collective ideal ego and superego to rally their people behind their cause, presenting war as a necessity for the survival and greatness of the nation. We thus witness a process of shifting libidinal investment from the ego to an external object, whether it be a country or an ideology. This process allows leaders to satisfy their narcissistic needs while giving the illusion of acting for the common good. But this illusion comes at a terrible cost, as it leads to devastating conflicts that repeat endlessly, despite their disastrous consequences.

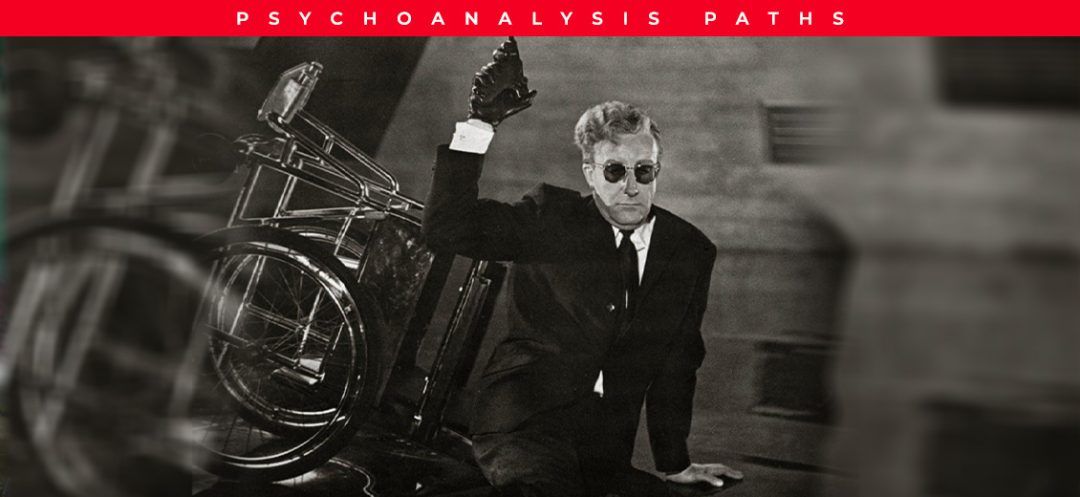

Stanley Kubrick’s film Dr. Strangelove offers us a fiercely satirical depiction of military and political leaders whose narcissism and ideological blindness drive the world to the brink of nuclear apocalypse. The characters, each more ridiculous than the last, convey a violent critique of political-military power. Kubrick brilliantly illustrates the sexual connotation of their enjoyment when driven by their warlike madness. This is masterfully represented from the opening credits, with scenes of planes coupling during mid-air refueling, and in the final shot where an officer rides a bomb in a sexual frenzy, letting out highly suggestive cries.

By highlighting the unconscious motivations hidden behind rational justifications, psychoanalysis invites us to question power and its limits, encouraging the search for paths toward peace and mutual understanding. As Owona suggests, only by transcending destructive narcissistic impulses and ideological blindness can we build a world where conflicts give way to dialogue, acceptance of others and cooperation between nations.

“A war is never against a country. A war is always a battle of egos and ideologies between a handful of people who use the country as their tool.”

This relevant and timely quote comes from the French-Ivorian footballer Stéphane Owona. It will help us examine the unconscious motivations that drive leaders to engage their nations in devastating conflicts.

At the heart of these motivations lies the pathological narcissism of these leaders. We know that narcissism is, in fact, a normal stage of human development. However, when this primary narcissism persists into adulthood, it can result in destructive behaviors. Narcissistic leaders tend to overestimate their abilities, perceive themselves as indispensable, constantly seek admiration from others and fundamentally lack empathy, even if they outwardly display the opposite. These personality traits can lead them to project their inflated egos onto the national and international stage, using their country as an extension of their own idealized self-image. Any opposition is seen as a personal threat to be eliminated. Their primary goal is to fulfill their need for control and glory, in a constant quest for recognition.

These pathological traits can drive such leaders to use war as a means of satisfying an ever-hungry and unsatisfied ego, ensuring their domination at the expense of the real interests of their country and people. Their patriotic slogans deceive infantilized citizens, who blindly sacrifice their most cherished possessions and even take pride in doing so. War thus becomes a tool to feed the sense of grandeur of those who consider themselves providential saviors, as well as to satisfy their megalomaniacal ambition to leave a historical mark, with no regard for the devastating consequences on people’s lives and property.

Ideological and dogmatic blindness is another crucial aspect of the psychological dynamic of these wartime leaders. A rigid attachment to an ideology can be understood as a defense mechanism, as described by Freud in Civilization and Its Discontents. This delusion manifests itself through the rejection of any contradictory information, the demonization of opponents and the justification of morally reprehensible actions in the name of their cause. Through the phenomenon of identification with the aggressor, some project their unresolved transgenerational traumatic wounds onto others by means of denial and splitting, which leads them to reject any contradictory reality. By desperately clinging to their ideology, they create a sense of certainty and security that shields them from existential anxiety and the questioning of their beliefs.

Attachment to the benefits of power is another powerful psychological driver in the development of conflicts. Freud’s concept of the death drive sheds light on this pathological attachment of leaders to their material and psychological advantages. Engaging in war, it is the death drive that invades their ego, not only allowing the abolition of the prohibition against murder but also prompting a morbid enjoyment in the destruction, suffering and death of others, reduced to mere waste.

The desire for domination manifests as an insatiable quest for wealth and privileges, a will to resist any change, regardless of the well-being of human lives. This dynamic reflects what Freud describes in his response to Einstein’s “Why War?” where he evokes the destructive impulses inherent in human nature. Leaders, by clinging to power and its privileges, permit themselves to unleash their destructive drives, all while justifying them through ideological or nationalistic motives.

In particularly pernicious cases, some leaders may regress to more primitive positions during times of great psychological tension, projecting their own fears and aggressions onto other nations to justify the conflict. Jacques Lacan, through his theory of the mirror stage, might interpret the need for recognition and affirmation of their image as leaders as an infantile motivation behind wars initiated by egocentric leaders. The underlying fragility of their ego drives them to develop and maintain an image of a grandiose self. They become masters at manipulating the collective ideal ego and superego to rally their people behind their cause, presenting war as a necessity for the survival and greatness of the nation. We thus witness a process of shifting libidinal investment from the ego to an external object, whether it be a country or an ideology. This process allows leaders to satisfy their narcissistic needs while giving the illusion of acting for the common good. But this illusion comes at a terrible cost, as it leads to devastating conflicts that repeat endlessly, despite their disastrous consequences.

Stanley Kubrick’s film Dr. Strangelove offers us a fiercely satirical depiction of military and political leaders whose narcissism and ideological blindness drive the world to the brink of nuclear apocalypse. The characters, each more ridiculous than the last, convey a violent critique of political-military power. Kubrick brilliantly illustrates the sexual connotation of their enjoyment when driven by their warlike madness. This is masterfully represented from the opening credits, with scenes of planes coupling during mid-air refueling, and in the final shot where an officer rides a bomb in a sexual frenzy, letting out highly suggestive cries.

By highlighting the unconscious motivations hidden behind rational justifications, psychoanalysis invites us to question power and its limits, encouraging the search for paths toward peace and mutual understanding. As Owona suggests, only by transcending destructive narcissistic impulses and ideological blindness can we build a world where conflicts give way to dialogue, acceptance of others and cooperation between nations.

Read more

Comments