Every week, we invite you to explore a striking quote from a great psychoanalyst to reveal its depth and richness. These lapidary, often provocative formulas open up new perspectives on the intricacies of the human psyche. By deciphering these quotes with rigor and pedagogy, we invite you on a fascinating journey to the heart of psychoanalytic thought to better understand our desires, anxieties and relationships with others. Ready to dive into the deep waters of the unconscious?

“We are never so defenseless against suffering as when we love.” — Sigmund Freud

This quote from Sigmund Freud is extracted from Civilization and Its Discontents, published in 1929. For the inventor of psychoanalysis, to love is to accept releasing ourselves from our shell, meaning suspending our usual defense mechanisms that we have unconsciously built throughout our existence. It is to consent to placing ourselves in a situation of extreme vulnerability, even without being entirely conscious of it, thus granting the loved one immense power over the course of our lives. Freud further elaborates: “We are never so hopelessly unhappy as when we have lost our love object or its love.” This is the very paradox of love: this feeling can be the source of the greatest satisfactions but can also turn into a true torment, especially when the loved one is absent, when we are driven by an excessive longing, by an unbearable sense of abandonment, finding ourselves like puppets at the mercy of the ups and downs of the romantic relationship.

The sacrifice of our defenses also involves the sacrifice of our narcissism, always for the benefit of the loved one who becomes the center of our universe, whose otherness confronts our self-esteem and generates frustration and suffering. According to Freud, part of our love for the other is, in reality, a love for an idealized version of ourselves that we project onto this other. This is why, in separation, we do not only mourn the loss of the other but also the loss of an idealized part of ourselves invested in the other.

Because the romantic relationship plunges us into a situation of great emotional dependence, archaic, infantile modes of relationships where the absolute predominance of the maternal object prevailed are reactivated. Love makes us regress to those states of passivity and helplessness of early childhood, expecting love, comfort, security, and a sense of well-being from the other.

Following Freud, Lacan offers further insight. For him, love is a much more tragic than tender feeling. It is a desperate attempt to fill an original lack, a fundamental incompleteness of the speaking being. But this quest is doomed to failure, for the dreamed union with the other is impossible. If love is a force that disrupts everything, it is because it is driven by an ever-unsatisfied desire, continuously seeking an object beyond the one that is present. True love, according to Lacan, then consists of recognizing and accepting this lack, in oneself and in the other. To truly love is to consent to difference, to the non-correspondence of desires. It is to open oneself to radical otherness, with the risks that this entails.

This conception of love as an encounter with lack echoes Melanie Klein’s work on the ambivalence of early emotional bonds. For her, love is inherently associated with hate, as the loved object is also a source of frustration. Early relationships with the mother, filled with gratifications and disappointments, shape our way of loving and managing the suffering that follows. Winnicott, on the other hand, emphasizes the importance of a “good enough” maternal love to help the child bear the anxiety of separation. These foundational experiences leave an indelible mark on our adult love life. For every love story, in a way, replays the drama of early separations. As Lacan shows with the mirror stage, the construction of our identity involves a painful detachment from the maternal body. This inaugural rupture leaves in us a nostalgia for a lost completeness, an unfulfilled desire for fusion with the other. And it is this desire that drives us toward the adventure of love, with its share of dreams and disappointments.

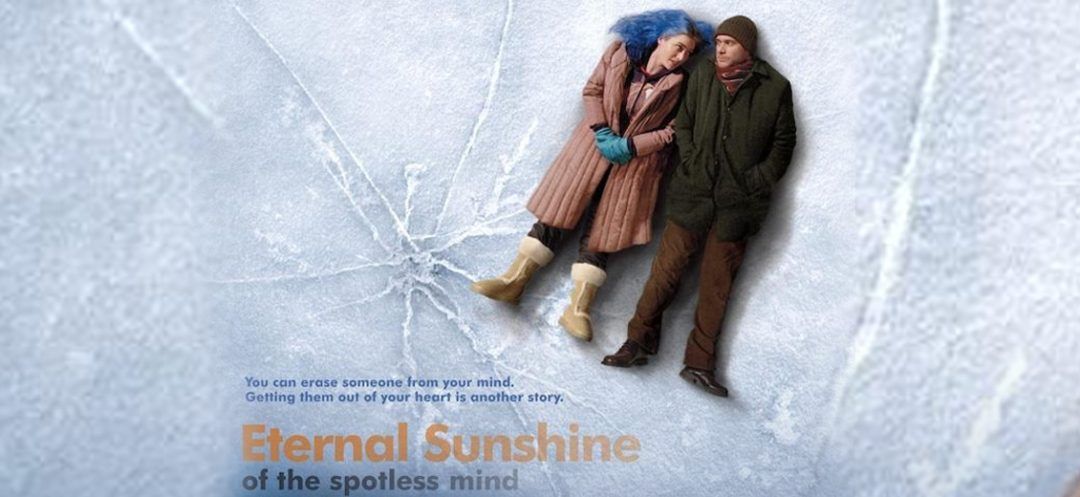

All of culture echoes this vulnerability in love. Literature, cinema, and painting are filled with stories where love is intertwined with suffering. From the cursed lovers Tristan and Isolde to the heartbreaks of Anna Karenina, and the torments of Werther, works of art continuously explore the many faces of love’s pain.

In Michel Gondry’s film, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, the complexity of the romantic relationship and the suffering that accompanies its loss illustrate our point well. Joel, heartbroken, overwhelmed by indescribable suffering, contacts the inventor of a machine to erase memories. But during the process, he paradoxically discovers that he now wants to preserve at all costs what he was trying to get rid of.

These fictional representations do more than move us. By plunging us into these love dramas, we revisit our own wounds, our own lacks. Like Joel, perhaps they can help us accept our vulnerability, tolerate our endangerment in the face of the risks of encounter and loss. For to love is to consent to our ontological insufficiency, to our fundamental incompleteness. It is to accept that the other is not everything to us, and we are not everything to the other. It is to renounce the chimera of fusion, of “being one,” to open up to otherness, to difference, to separation. And it is in this space between oneself and the other, in this gap that constitutes us, that love can then unfold all its creative potential.

[readmore url="https://thisisbeirut.com.lb/culture/273041"]

“We are never so defenseless against suffering as when we love.” — Sigmund Freud

This quote from Sigmund Freud is extracted from Civilization and Its Discontents, published in 1929. For the inventor of psychoanalysis, to love is to accept releasing ourselves from our shell, meaning suspending our usual defense mechanisms that we have unconsciously built throughout our existence. It is to consent to placing ourselves in a situation of extreme vulnerability, even without being entirely conscious of it, thus granting the loved one immense power over the course of our lives. Freud further elaborates: “We are never so hopelessly unhappy as when we have lost our love object or its love.” This is the very paradox of love: this feeling can be the source of the greatest satisfactions but can also turn into a true torment, especially when the loved one is absent, when we are driven by an excessive longing, by an unbearable sense of abandonment, finding ourselves like puppets at the mercy of the ups and downs of the romantic relationship.

The sacrifice of our defenses also involves the sacrifice of our narcissism, always for the benefit of the loved one who becomes the center of our universe, whose otherness confronts our self-esteem and generates frustration and suffering. According to Freud, part of our love for the other is, in reality, a love for an idealized version of ourselves that we project onto this other. This is why, in separation, we do not only mourn the loss of the other but also the loss of an idealized part of ourselves invested in the other.

Because the romantic relationship plunges us into a situation of great emotional dependence, archaic, infantile modes of relationships where the absolute predominance of the maternal object prevailed are reactivated. Love makes us regress to those states of passivity and helplessness of early childhood, expecting love, comfort, security, and a sense of well-being from the other.

Following Freud, Lacan offers further insight. For him, love is a much more tragic than tender feeling. It is a desperate attempt to fill an original lack, a fundamental incompleteness of the speaking being. But this quest is doomed to failure, for the dreamed union with the other is impossible. If love is a force that disrupts everything, it is because it is driven by an ever-unsatisfied desire, continuously seeking an object beyond the one that is present. True love, according to Lacan, then consists of recognizing and accepting this lack, in oneself and in the other. To truly love is to consent to difference, to the non-correspondence of desires. It is to open oneself to radical otherness, with the risks that this entails.

This conception of love as an encounter with lack echoes Melanie Klein’s work on the ambivalence of early emotional bonds. For her, love is inherently associated with hate, as the loved object is also a source of frustration. Early relationships with the mother, filled with gratifications and disappointments, shape our way of loving and managing the suffering that follows. Winnicott, on the other hand, emphasizes the importance of a “good enough” maternal love to help the child bear the anxiety of separation. These foundational experiences leave an indelible mark on our adult love life. For every love story, in a way, replays the drama of early separations. As Lacan shows with the mirror stage, the construction of our identity involves a painful detachment from the maternal body. This inaugural rupture leaves in us a nostalgia for a lost completeness, an unfulfilled desire for fusion with the other. And it is this desire that drives us toward the adventure of love, with its share of dreams and disappointments.

All of culture echoes this vulnerability in love. Literature, cinema, and painting are filled with stories where love is intertwined with suffering. From the cursed lovers Tristan and Isolde to the heartbreaks of Anna Karenina, and the torments of Werther, works of art continuously explore the many faces of love’s pain.

In Michel Gondry’s film, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, the complexity of the romantic relationship and the suffering that accompanies its loss illustrate our point well. Joel, heartbroken, overwhelmed by indescribable suffering, contacts the inventor of a machine to erase memories. But during the process, he paradoxically discovers that he now wants to preserve at all costs what he was trying to get rid of.

These fictional representations do more than move us. By plunging us into these love dramas, we revisit our own wounds, our own lacks. Like Joel, perhaps they can help us accept our vulnerability, tolerate our endangerment in the face of the risks of encounter and loss. For to love is to consent to our ontological insufficiency, to our fundamental incompleteness. It is to accept that the other is not everything to us, and we are not everything to the other. It is to renounce the chimera of fusion, of “being one,” to open up to otherness, to difference, to separation. And it is in this space between oneself and the other, in this gap that constitutes us, that love can then unfold all its creative potential.

[readmore url="https://thisisbeirut.com.lb/culture/273041"]

Read more

Comments