Every week, we invite you to explore a striking quote to reveal its depth and richness. These lapidary, often provocative formulas open up new perspectives on the intricacies of the human psyche. By deciphering these quotes with rigor and pedagogy, we invite you on a fascinating journey to the heart of psychoanalytic thought to better understand our desires, anxieties and relationships with others. Ready to dive into the deep waters of the unconscious?

"Do not rush towards adaptation. Always keep some inadaptability in reserve." – Henri Michaux

This is the recommendation transmitted to us by Henri Michaux, a visionary poet and innovative artist, a major figure of the 20th-century avant-garde. From exploring the limits of consciousness to rejecting sterilizing social conventions, he made these the very heart of his creative approach. In 1922, he himself directed a special issue dedicated to Sigmund Freud in the magazine *Le Disque vert*. It is therefore not surprising that this exhortation deeply resonates with psychoanalytic thought.

The inadaptability claimed by Michaux originates from his harsh early experiences of uprooting and loss. Born in Belgium in 1899, he experienced a childhood marked by the absence of his father and much existential instability. Later, the heartbreaking grief of his wife Marie-Louise's death in 1948 left him in indescribable suffering. From this place of fundamental inadaptability to the world, Michaux continually reinvented his relationship with the body and language. Although he was often associated with certain cultural movements, he claimed his artistic and intellectual independence to remain free in his explorations.

What this thinker advises us is, first of all, not to rush towards adapting to social conventions, risking the loss of our individuality and authenticity. And also, to preserve a part of ourselves that is unique and true to our subjective identity—a source of creativity, critical reflection, and resistance to all kinds of conformist forces.

Cultivating one's inadaptability as an inner resource is to preserve the most intimate and living part of oneself, the part that remains rebellious against external determinations. This position echoes the notion of the "true self" theorized by Donald W. Winnicott, which we have already discussed. For the British psychoanalyst, the true self is the authentic core of the personality, the seat of creativity, as opposed to the "false self," an entity shaped by sociocultural conformity. In Michaux's view, the injunction to keep "some inadaptability in reserve" appears as an invitation to never completely sacrifice one's true self to the alienating demands of the world.

This radical rejection of adaptation advocated by Michaux also makes sense in light of the notion of "normopathy" coined by psychoanalyst Joyce McDougall, which refers to behaving in an abnormally normal manner. By this notion, the psychoanalyst describes a complete and excessive submission to the norms of a fundamentally consumerist society, leading the individual to lose contact with their inner life and their own desires. Normopathic individuals seek to fully adapt to sociocultural expectations, imitating the fashions and norms displayed on social media, at the expense of their authenticity and subjective identity. In the face of this risk of psychic asphyxiation, Michaux's inadaptability serves as a lifesaving valve, ensuring fidelity to oneself, which is essential for mental balance and creativity.

One can also see in this dynamic an echo of the notion of "negative capability" developed by British psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion: the ability to tolerate doubt, uncertainty, lack of immediate answers, contradictions, a necessary ground for the emergence of a resolutely creative original thought. Negative capability offers the opportunity for a subject to remain open to new ideas and perspectives without rushing into premature and alienating choices. For Michaux and Bion alike, it is in the gaps of adaptation that the creative genius takes root.

Echoing Michaux's invitation and personal experiences, recent studies have highlighted a correlation between creativity and certain mental disorders, as well as with the experience of controlled use of hallucinogenic substances. This relationship could be explained by several factors, ranging from the emotional intensity associated with these states, conducive to nurturing artistic expression, to the reduction of social inhibition during certain phases, promoting creative boldness, and unusual experiences stimulating originality.

Without falling into an inappropriate generalization of these correlations, Michaux's intuition about the creative power of inadaptability finds a resounding confirmation among many artists and writers who have made their existential eccentricity the very material of their work.

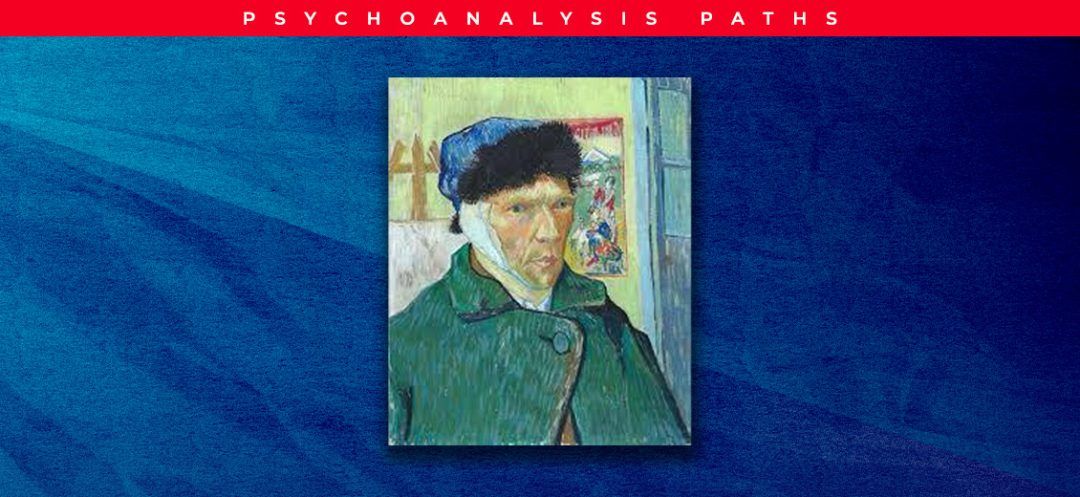

We can cite Vincent Van Gogh, who found in painting a sublimation of his struggle against depression and psychosis, bequeathing us paintings of unparalleled pictorial and emotional intensity.

The Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, for her part, transmuted her somatic and psychic pain into striking self-portraits, while the Japanese avant-garde artist Yayoi Kusama made her hallucinations and obsessive-compulsive disorders the source of a unique plastic universe, populated by psychically invasive dot motifs. Francis Bacon, meanwhile, explored themes of suffering, violence, and psychic and physical fragmentation in raw and disturbing productions, illustrating another reflection by Henri Michaux: "Who leaves a trace leaves a wound."

In literature, several works explore themes of inadaptability and resistance to oppressive forces that impose subjugation.

Meursault, in The Stranger by Albert Camus, refuses to obey cultural expectations, remaining inadaptable to his social environment. Michaux himself often wrote about his feeling of being a stranger, both in society and in his own body.

Franz Kafka's The Trial illustrates the absurdity and impossible adaptation to an oppressive and utterly absurd political-judicial system.

Finally, we can mention a major dystopian work: 1984 by George Orwell, in which the main character struggles, in his own way, against a despotic regime that imposes total submission and absolute conformity on its citizens, the anti-hero seeking to preserve his humanity in the very assertion of his inadaptability.

A little gift: listen to the paradoxical performance of the sultry German punk and new-age singer Nina Hagen, who nonetheless manages to move us with this traditional religious song that has permeated the childhood of many listeners: Stille Nacht.

Through his exhortation, Michaux does not invite us to a nihilistic rejection of the world but rather to a form of inner resistance to homogenizing forces. Keeping "some inadaptability in reserve" is to preserve within oneself a subjective space of play and inventiveness, from which it is possible to continually renew one's relationship with the world and with creation. As the poet adds: "A whole life is not enough to unlearn what, naive, submissive, you let be put in your head, without thinking of the consequences."

[readmore url="https://thisisbeirut.com.lb/culture/273041"]

Read more

Comments