Every week, we invite you to explore a striking quote from a great psychoanalyst to reveal its depth and richness. These lapidary, often provocative formulas open up new perspectives on the intricacies of the human psyche. By deciphering these quotes with rigor and pedagogy, we invite you on a fascinating journey to the heart of psychoanalytic thought to better understand our desires, anxieties and relationships with others. Ready to dive into the deep waters of the unconscious?

“There Is No Such Thing as a Baby” — Donald W. Winnicott

It was during a lecture before the members of the British Psychoanalytical Society in 1943 that Donald W. Winnicott uttered this intriguing phrase that revolutionized our understanding of the somato-psychic development of infants: it invites us to a radical shift in perspective.

Winnicott proposes that we abandon our adult perspective and understanding of a child and replace it with a renewed vigilance to the complexity of the bonds that form between the infant and their environment.

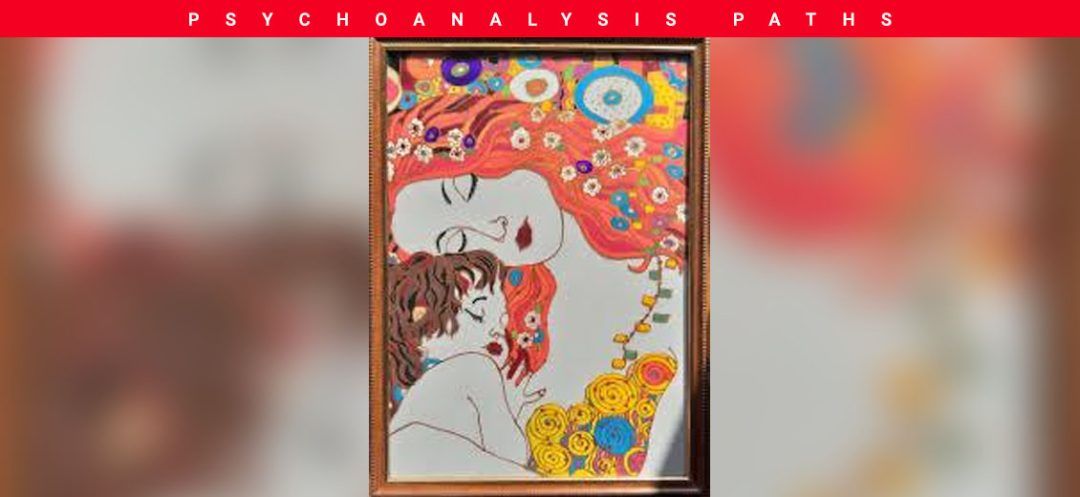

For this psychoanalyst, who himself suffered in early childhood from a cold and depressed mother, a baby only exists as part of a relationship, one that is established very early with their mother or substitute. The baby and their maternal environment form an inseparable unit, a “nurturing couple,” whose subtle and constant interactions provide the fertile ground for their present and future somato-psychic development.

Consider breastfeeding moments during which the mother and her infant become one, united in a nurturing symbiosis, where heartbeats and breathing rhythms are synchronized. Or, observe the “holding,” when the mother supports the child not only in her arms but contains them through her care, protection, rocking and tender words. She tempers intense excitations, promotes the integration of the self and the sense of being. Or the “handling” that helps the child develop an interiority and bodily boundaries.

These repeated, daily experiences strongly illustrate this idea of interdependence, thus making it entirely impossible to consider the baby as an autonomous entity.

Winnicott goes even further: he highlights the importance of “primary maternal preoccupation” during the first three or four months of life, this state of grace where the mother, entirely united with her child, is in harmony with their slightest somato-psychic manifestations, demonstrating exceptional sensitivity and empathy. This fusion-like complicity allows the infant to live the necessary magical illusion that they themselves are the creator of this universe that satisfies their needs and desires. For example, when the child cries and almost instantly, the mother responds to their call, the child feels that it is through their magical power that they have made the one who ends their suffering appear. Or when they are hungry, and the warm milk naturally arrives to soothe and satisfy them. This illusion of omnipotence, far from being an artifact, is in reality the necessary foundation for the construction of a sense of continuity of being, the basis of a becoming self.

Imagine or recall the baby fixing their gaze on their mother’s: they discover their own image. Winnicott tells us that when the baby looks at their mother, her face reflects what she sees, thinks and feels about them. He describes “those babies tormented by maternal failure, who study the variations of her face to predict her mood, as one scrutinizes the sky to know the weather.”

The first games, such as the famous “peek-a-boo” during which the mother disappears behind her hands and then reappears, take on a new dimension in light of Winnicott’s thought. The baby smiles, laughs heartily, not only out of pleasure, enjoying the surprise, but they learn, little by little, that their mother continues to exist even when they do not see her. They thus integrate the experience of object permanence, a crucial step in building a sense of internal security and self-confidence, a prerequisite for acquiring “the capacity to be alone.”

The revolution triggered by Winnicott lies in this shift in focus, this displacement of the center of gravity from the individual to the mother-baby dyad. It is the recognition of the active, determining role of the maternal environment in early psychic development. It is an invitation to adopt a unique, constantly renewed perspective on the subtle and lasting interactions that weave, day after day, the complex psychic coexistence between mother and child.

This vision has profound implications, not only for understanding the somato-psychic development of the infant but also for the future adult. Our childhood experiences will have deep repercussions on our future lives in more than one way.

Thus, the experiences of security and trust lived with the mother shape our ability to establish intimate bonds with others.

Similarly, the way the mother responded to our needs and desires supports our self-confidence. If she valued us, supported us, desired us, showed empathy, we will develop a sense of security and confidence. If, on the contrary, she was absent, depressed, rejecting, the sense of our identity and self will be weakened.

The mother-child relationship will also be decisive in our perception of our future role as parents. At that time, we will tend to reproduce the family patterns perceived and felt. The memories of our own childhood will unconsciously guide our relationship with our children.

Our mental health in adulthood will also not escape the determinism of infant relationships. Insecure, inconsistent bonds will increase the risks of depression and anxious experiences. A deficient emotional attachment can isolate the adult in their relationships or prevent them from establishing lasting connections.

Finally, a child’s relationship with a “good enough” mother will promote the development of autonomy, while an overprotective relationship will hinder this process.

Not to mention that understanding the significance, for a child, of a “comfort object,” the quintessential transitional object, will open the way to a transitional space that will be the source from which all exploration and flowering of creative opportunities in adulthood will draw.

Read more

Comments